This 99-Million-Year-Old Dinosaur Tail Trapped in Amber Hints at Feather Evolution

The rare specimen provides new insights into how feathers came to be

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/50/f2509f0c-e423-4f14-a5c1-0a846caa4070/tail-with-ants-overview-original-background.jpg)

Once thought to to be scaly-skinned beasts, many dinosaurs likely sported fantastical feathers and fuzz. Though early ancestors of birds, many pieces of their evolutionary timeline remain unclear. But a recent find could fill in some of these gaps: the tip of a fuzzy young dino's tail encased in amber.

In 2015, Lida Xing, a researcher from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, was wandering through an amber market in Myanmar when he came across the specimen on sale at a stall. The people who had dug it out of a mine had thought that the fossilized tree resin contained a piece of some sort of plant and were trying to sell it to be made into jewelry. But Xing suspected that the hunk of ancient tree resin could contain a fragment from an animal and brought it to his lab for further study.

His investment paid off.

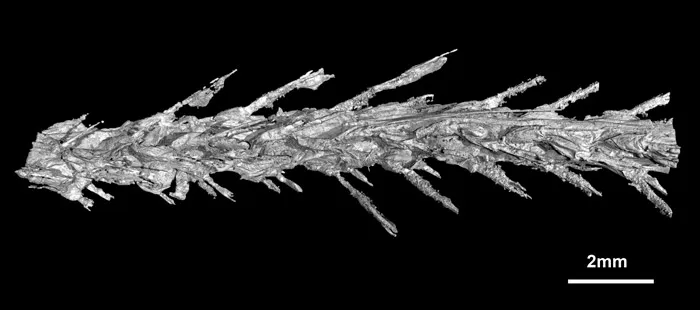

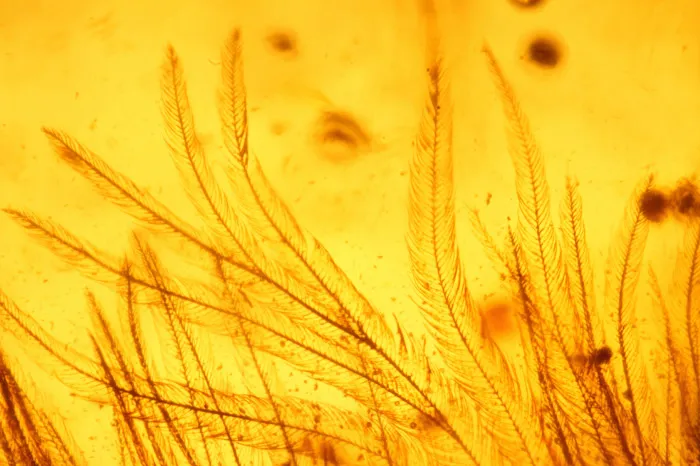

What looked like a plant turned out to be a tip of a tail covered in simple, downy feather. But it’s unclear exactly what kind of creature it belonged to. Researchers took a closer look at the amber piece using CT scans and realized that it belonged to a true dinosaur, not an ancient bird. The researchers detailed their find in a study published in the journal Current Biology.

"We can be sure of the source because the vertebrae are not fused into a rod or pygostyle as in modern birds and their closest relatives,” Ryan McKellar, a researcher at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum and co-author of the study says in a statement. “Instead, the tail is long and flexible, with keels of feathers running down each side."

Without the rest of the skeleton, it's unclear exactly what kind of dinosaur this tail belonged to, though it was likely a juvenile coelurosaur, a creature closely related to birds that typically had some kind of feathers. And what’s most intriguing about this 99-million-year-old fossil are the feathers. In the past, most information on dinosaur feathers has come from two-dimensional impressions left in stone or feathers that weren’t attached to the rest of the remains. This fossil could help settle a debate over how feathers evolved in the first place, says Matthew Carrano, curator of Dinosauria at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Because fossils are relatively rare, evolutionary biologists have turned to studying the embryos of modern birds to get a sense of how feathers might have developed over millions of years. But while it’s a good way to put together an evolutionary roadmap, they still need to find the right signposts to make sure that their thinking is on the right track.

“All the little parts of a feather kind of Velcro together, so you can wave a feather in the air and it doesn’t change shape, which is the point if you’re flying with it,” Carrano tells Smithsonian.com.

For years, Carrano says paleontologists have been split over a seemingly simple question: which came first, the “Velcro” that holds feathers together, or their overall structural form. However, while the feathers of this new find feature tiny little hooks common to bird feathers, they have much more in common with loose, downy feathers than the stiff pinions that modern birds use for flight. That suggests that the hooks, or so-called barbules, came first.

“If you look at them, they’re kind of waving all over the place,” Carranno says. “If you had a really structured feather and you had these barbules, they shouldn’t be floating all over the place. They should be pretty stiff.”

These feathers certainly didn’t help this particular dinosaur to fly, but they may have helped it keep warm and dry, kind of like fur. And the feathers aren't the only thing in this piece of amber that Carrano finds interesting—it also has tiny, ant-like insects entombed within it.

“I’d personally love to know what these insects are,” Carrano says. “You almost never find a dinosaur and an insect fossil together because they just don’t preserve in the same kind of setting. But here they are, right?”

While the feathered dinosaur tail may be the flashiest find, this chunk of amber could still hide many more clues about the ancient just waiting for scientists to unlock.