75 Years Ago, the Secretary of the Navy Falsely Blamed Japanese-Americans for Pearl Harbor

The baseless accusation sparked the road to the infamous internment camps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/73/db731cdb-91ff-46c7-9914-311974a3b51e/posted_japanese_american_exclusion_order.jpg)

Last week, people across the United States took time to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack on the Hawaiian naval base by the Japanese navy was one of the most shocking events of the 20th century and spurred the U.S.’ entrance into World War II. Just a few days later, Frank Knox, the Secretary of the Navy, made a baseless claim that sparked one of the most shameful elements of American history—the forced internment of Japanese-American citizens.

Days before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Knox had tried to assure other officials that the armed forces were prepared for anything, Fred Barbash reports for The Washington Post. But then came the bombing, which ultimately killed more than 2,400 people. In his first press conference after the attacks on December 15, Knox gave credence to baseless fears sweeping the country that Japanese-American citizens had helped get the drop on the unsuspecting boys in Hawaii.

Knox wasn’t the first or the last to voice fears that a so-called “fifth column” of Japanese-American citizens had given a helping hand to their ethnic homeland’s military. Those fears had already been swirling, Barbash reports. But Knox was one of the first government officials to publicly voice support for this conspiracy theory—an opinion that had serious consequences for thousands of American citizens that is still felt today.

According to the 1982 report by the Wartime Relocation Commission, which examined the fallout of American government’s efforts to relocate and intern Japanese-Americans during World War II, “the alarm Knox had rung gave immediate credence to the view that ethnic Japanese on the mainland were a palpable threat and danger...The damage was remarkable.”

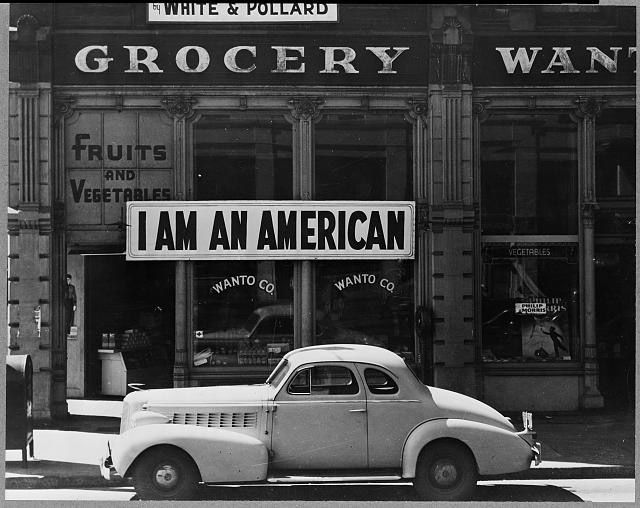

Partially as a result of Knox’s announcement and the fears he stoked, while American military forces geared up to enter the war, the government prepared camps to house Japanese-American citizens. In the days after Pearl Harbor, anyone of Japanese descent was forced out of parts of the West Coast due to issues of national security. Meanwhile, Japanese-Americans faced growing hostility from their neighbors who blamed them for the attacks simply because of their heritage, Johnny Simon reports for Quartz.

This was all despite the fact that even a report by the Office of Naval Intelligence at the time found that Japanese-American citizens posed no significant military threat. As David Savage reported for The Los Angeles Times, in 2011 acting Solicitor General Neal Katya shared with the public that Charles Fahy, then the solicitor general, actively suppressed the report in order to defend President Franklin Roosevelt’s decision to sign Executive Order 9066, which ordered the internment or incarceration of more than 100,000 American citizens of Japanese descent through the end of World War II.

The scars left by these actions resonate 75 years later. Just this week, The Los Angeles Times apologized for publishing two letters in response to an article about the internment camps that fell back on the same, false stereotypes that many Japanese-Americans experienced during World War II. In a note on the original piece, its editor-in-chief and publisher said the letters did not meet the newspaper’s standards for “civil, fact-based discourse.”

Even though in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which offered every Japanese-American interned in the camps during the war a formal apology and $20,000 in compensation, America's internment camp past stands as a stark reminder of how the American government has treated minority groups.

The shameful history that led to their creation highlights how insidious and impactful words can be, particularly when they are spoken by people in authority; a lesson that is imperative to be learned from and not repeated.