Europe Is a Great Place to Be a Large Meat-Eater

In a rare success story for wildlife, bears, lynx, wolverine and wolves are increasing in numbers across the continent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/a7/25a7320c-a3b7-49cd-b217-90326e845a19/lynx.jpg)

Wildlife conservation is a field often beleaguered with bad news. In Europe, however, large carnivores are proving to be the exception to the rule. According to research compiled by about 75 wildlife experts, brown bears, Eurasian lynx, gray wolves and wolverines are all on the rise across the continent. This conservation success demonstrates that people and large carnivores can indeed coexist, the team says.

The findings are based on the best available standardized information about the abundance and range of large carnivores in every European country except Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. The work also excludes tiny nations like Lichtenstein and Andorra. The team collected both historical data compiled from World War II to the 1970s and the most recent population estimates, so they could compare how the numbers of animals have changed over time. The bulk of those figures came from experts affiliated with the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe. Professionals working at universities and conservation groups and local and national governments also supplied data.

“The numbers are often the official ones reported to the European Union,” lead author Guillaume Chapron, an ecologist at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, says in an email. “The estimates represent the best available knowledge.”

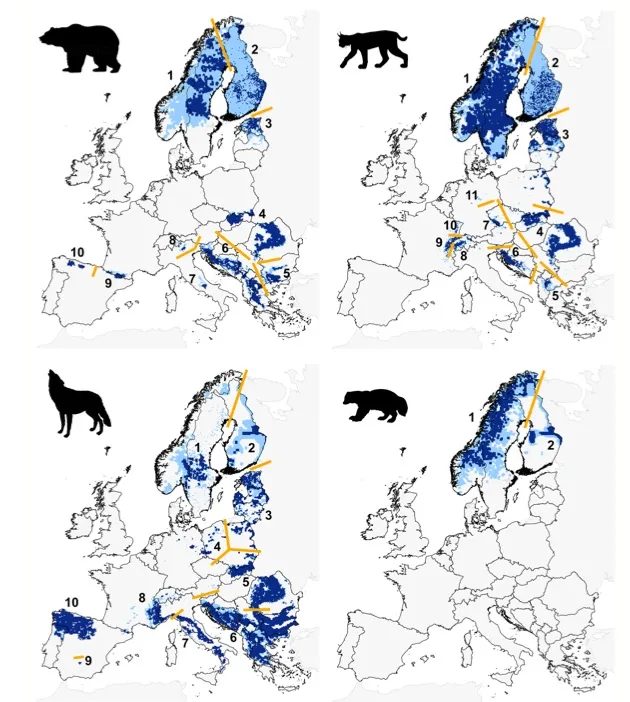

All together, large carnivores occupy roughly one-third of the mainland European continent, team reports today in Science. Every country except Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Luxemburg features a permanent population of at least one of the four species evaluated in the study, and carnivore sightings have been reported recently in places not yet known to harbor breeding populations of those animals. Additionally, the team found that most of the animals live outside of protected areas, frequently sharing landscapes with people.

The data indicated that brown bears are the most abundant carnivores, with an estimated population of 17,000 individuals divided into 10 main populations. Wolves, however, are found in the most places, ranging over 28 countries. Wolverines occur in the fewest places—just Sweden, Norway and Finland, which feature the cold, high-altitude habitats the animals require—but their numbers are on the rise. The Fennoscandia region also acts as Europe’s primary big carnivore hot spot, since it’s the only place where all four species can be found.

These successes are all the more significant because large carnivores are especially tricky to manage. People often harbor negative connotations about meat-eaters—the big bad wolf or the man-eating bear. Predators also usually need a lot of space, with ranges sometimes spilling across the borders of several countries. A single pack of wolves may roam throughout the Balkans, for example, or a male lynx might prowl the forests of both Norway and Sweden. Therefore, protecting carnivores in places as nation-crowded as Europe requires transboundary management and agreement among multiple populations that carnivores are worth having around.

As the authors point out, Europe seems to have succeeded in doing just that. This is probably due to a combination of factors, including post-World War II stability in most countries, pan-European legislation dating back to the 1970s that protects wildlife, an increasing number of people abandoning the countryside for the city and growing populations of other animals, such as deer, which large carnivores depend on for food.

There are challenges remaining, however. Some sources in Romania, for example, indicate that bear population estimates reported to the government might be exaggerated due to bribes from frustrated farmers and trigger-happy hunters. As Chapron points out, though, “any bribed or corrupted numbers would concern only very few countries—if any—and would not affect the general trends that we report in the paper on a continental scale.”

A bigger problem, the researchers acknowledge, is cultural disinclination in certain countries and professions toward some carnivores. Illegal wolf killing is still commonplace in rural Norway, for example. In June, two men in Sweden were sentenced to jail time for killing a female wolf. And Austrian poachers wound up hunting an introduced population of bears until they went locally extinct. While positive feelings toward carnivores are prevailing overall, “the underlying negative forces are still present and could reemerge as a result of ecological, social, political or economic changes.”

Although ongoing monitoring is necessary to ensure things continue to trend in a favorable direction for carnivores, the team writes that the current situation in Europe overall offers hope that wildlife and humans can find a way to live together in other places around the world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)