Cougars on the Move

Mountain lions are thought to be multiplying in the West and heading east. Can we learn to live with these beautiful, elusive creatures?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/6c/a76c3c60-4236-4ec9-a90d-4b698d727379/mountain-lion-01623.jpg)

Standing on the lip of a steep cliff on the Uncompahgre Plateau in western Colorado, Ken Logan rotates a telemetry antenna to pinpoint the radio signal of a female cougar designated F-7. He wants to tag F-7's cubs, which she has stashed in a jumble of rocks on the mountainside below. But she won't leave them, and Logan is wary. In 25 years of studying cougars, he and his team have had about 300 "encounters" and have been challenged six times. "And five of the six times," he says, "it was a mother with cubs. So what we don't want today is mom there with her cubs behind her."

Logan is at the beginning of a ten-year, $2 million study of mountain lions on 800 square miles. This native American lion—also called cougar, catamount, panther and puma—is the world's fourth largest cat. It ranges more widely throughout the Americas than any mammal except human beings. There's a lot at stake for cougars throughout the West, where beliefs about the cat are more often rooted in politics, emotion and guesswork than in hard facts. The animals are so elusive that no one knows for certain how many exist. "We're studying a phantom in the mountains," says Logan.

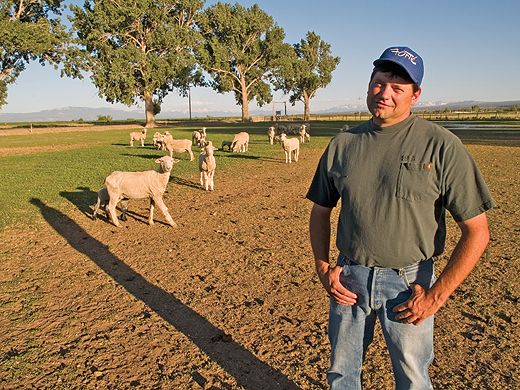

Are cougars destructive, overabundant predators that kill livestock and deer (robbing hunters of that opportunity), or splendid, overhunted icons that deserve protection? And how dangerous are they to people? Fatal attacks in the United States and Canada are rare—21 in the past 115 years—but 11 have happened since 1990.

In 1990, Californians voted to outlaw hunting cougars entirely. But most Western wildlife agencies have gone in the other direction in the past few decades, increasing the number that could be killed annually. In 1982, hunters in ten Western states killed 931 cougars, and by the early 2000s the number was topping 3,000. The number of hunting permits surged between the late 1990s and early 2000s after many states either expanded the season for lions, lowered the cost of licenses, raised bag limits—or all three. In Texas, Logan's home state, cougars—even cubs—can be killed year-round without limit.

Because it's so hard for wildlife agencies to get accurate counts of cougars, Logan and Linda Sweanor (Logan's spouse and fellow biologist) devised a conservative strategy for managing them by dividing a state into different zones: for sport hunting, for controlled killing in areas crowded with people or livestock, and for cougar refuges, which Logan calls "biological savings accounts." Many of the country's cougar experts have recommended that wildlife agencies adopt such zone management.

That hasn't happened. "Other political interests came to bear," Logan says dryly, referring mostly to ranchers and hunters. "At least the science is there now. I think policymakers and managers will go back to it, because management based on politics is going to fail."

Abstract of an article by Steve Kemper, originally published in the September 2006 issue of SMITHSONIAN. All rights reserved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)