It’s a splendid day for a turn around a graveyard: dark, damp, forbidding. A thin mist billows like a mourner’s veil between the iron gates of Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church, and moisture drips from the yews like tears. In this Northern Irish churchyard, burial plots line the paths like little marble farms for the dead.

I meander past the Boho High Cross of County Fermanagh, a tenth-century monument whose carvings feature scenes from Genesis and the Baptism of Christ. I skirt graves marked McAfee, McCaffrey, McConnell, McDonald, McGee...At last, atop a bosky knoll, I reach the weatherworn headstone of James McGirr, a parish priest who died in 1815, age 70.

Out here in the Boho Highlands, part of the West Fermanagh Scarplands, five miles from the border with the Republic of Ireland, there’s a longstanding belief among parishioners that the earth Father McGirr was buried under had almost miraculous curative powers. “The good father is said to have been a faith healer,” says Gerry Quinn, a microbiologist who grew up in the area. “On his deathbed he supposedly declared: ‘After I die, the clay that covers me will cure anything that I was able to cure when I was with you while I was alive.’” This led to a curious local custom: Petitioners will kneel beside the plot, remove a thumbnail-size patch of dirt and put it into a cotton pouch. “They will then bring the packets home—taking pains not to speak to anyone they encountered on the road—and place the pouches under their pillows,” Quinn says. “The soil is believed to alleviate many minor ailments, like flesh wounds and sore throats.”

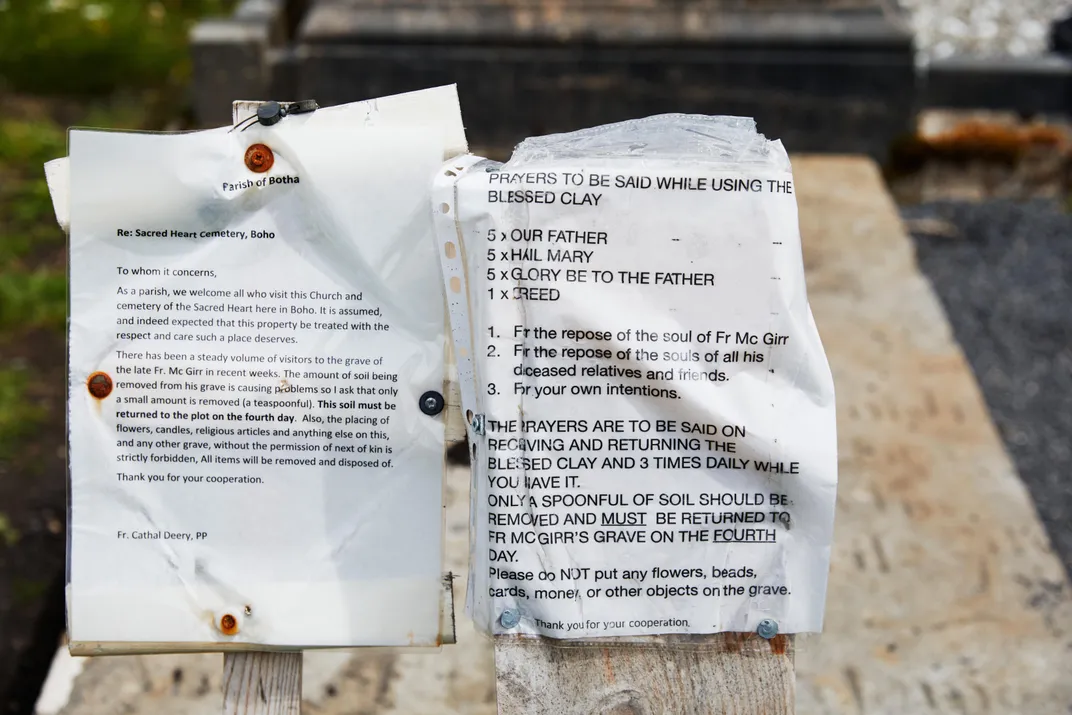

On this particular afternoon, the grave is carpeted with spoons—teaspoons, tablespoons, soup spoons, even a grapefruit spoon. “To dig with,” Quinn more or less explains. The wooden post beside the priest’s headstone instructs visitors what prayers to offer up to him and how to sample the “blessed clay”: ONLY A SPOONFUL OF SOIL SHOULD BE REMOVED AND MUST BE RETURNED TO FR MCGIRR’S GRAVE ON THE FOURTH DAY. “According to legend,” says Quinn, “failure to take back the soil within four days brings very bad luck.”

For those of us who don’t subscribe to fable, this antic County Fermanagh folk remedy may strike a skeptical chord. But legend often reveals truth that reality obscures. Quinn, who has since moved on to Northern Ireland’s Ulster University, and his former colleagues at Swansea University Medical School in Wales recently discovered that the hallowed Boho (pronounced Bo) dirt possesses unique antibiotic properties—and may provide a new weapon in the long-running arms race against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

According to the Swansea researchers, the soil over Father McGirr contains a previously unknown strain of Streptomyces, a genus of the phylum Actinobacteria, which has produced about two-thirds of all currently prescribed antibiotics. Soil bacteria secrete chemicals to inhibit or kill competing bacteria, and this particular strain of Streptomyces happens to mess with several disease-causing pathogens that have become impervious to conventional antibiotics. Among the most notorious of these increasingly common superbugs is Staphylococcus aureus, better known as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), which is responsible for about a third of “flesh-eating bacteria” infections in the United States.

It was Alexander Fleming’s serendipitous discovery of penicillin in 1928—mold accidentally contaminated a petri dish in his lab at St. Mary’s Hospital in London and some of the Staphylococcus bacteria he’d been growing in the dish were destroyed—that allowed effective treatment of many infections that had routinely killed people. But superbugs annul the success of contemporary therapies by constantly mutating into tougher, more virulent strains. Like teenagers tapping out text messages, they’re adept at transmitting immunity genes to other pathogens.

Having evolved defenses to withstand the onslaught of modern antibiotics, superbugs are considered among the gravest and most intractable of global menaces. According to a new report from the United Nations, antibiotic-resistant infections claim at least 700,000 lives every year—including 230,000 deaths from drug-resistant tuberculosis alone. By 2050, the U.N. says, that toll seems likely to rise dramatically, with up to ten million people dying annually if “immediate, coordinated and ambitious action” does not occur. In this case, “action” means reducing the misuse of antibiotics—either deploying them for no good reason against illnesses like the flu or discontinuing an antibiotic before it was fully effective. Both practices contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

It has been decades since drug researchers or medical scientists have discovered a new class of antibiotics: Most of the antimicrobial drugs in use today are just modifications of drugs that have been around more than half a century. In the search for new germ killers, researchers in the small but promising field of ethnopharmacology are investigating ancient herbal remedies and healing techniques and folk medicines. Which is what sent Quinn back to the graveyard at Sacred Heart.

* * *

Local knowledge of Boho’s unique terra firma may date to the mystical Druids, who occupied the land around 1,500 years ago, and perhaps stretches as far back as the Neolithic Age 3,500 years before that. “The legend of the magical soil is something that’s resonated down through the ages,” says Dessie McKenzie, owner and barkeep of the Linnet Inn, Boho’s only pub. (And of equal convenience to the local citizenry, he’s also the undertaker.) “Every town and village in Ireland seems to have a cure that involves taking something from someone and giving it back. Ours mirrors the mysterious side of Irish mythology, all these hidden secrets.”

Quinn heard the tale of McGirr’s soil from a great-uncle who also insisted that he could cure jaundice by foraging natural ingredients in the mountains. “You can look at this as an old wives’ tale and decide it’s all just superstition,” Quinn says. “Or you can check into it thoroughly to see if there’s anything in the soil that produces antibiotics. I prefer to check.”

Quinn steps out of the shadow of The Big Fish—a statue of a salmon dominating Belfast’s Donegall Quay—and into the bright sun like an explorer about to cross the Sahara on foot. He’s a sharp, ten-penny nail of a man whose intensity is leavened by a broad smile. He can be genial enough when circumstances demand, but if he’s telling you the latest dirt, you need to pay attention, and what you thought was a casual conversation might quickly take on the aspect of a thesis defense.

“In the days before antibiotics, healing was a spiritual event,” he says. “Healthy people in the countryside got ill without any possibility of recovery. Any cure is miraculous, which is why it’s no coincidence that religion is interwoven with the healing arts.”

He cites a priest who has dismissed the cure as paganism. “It is perhaps a bit of paradox that clergy could be on the side of the rationalists and the scientists on the side of the unknown,” he says. “People are actually seeking out the cure not because of Father McGirr’s prophecy, but because there has been some scientific investigation.”

Quinn launched his research at Swansea University where he was a postdoctoral student. “I was looking for stuff that could cure incurable infections and treat incurable conditions,” he recalls. Paul Dyson, a molecular microbiologist, heads the Applied Molecular Microbiology research team at Swansea, and he had been conducting studies that isolated Streptomyces microbes directly from arid habitats, including Tibetan plateaus and a Saudi Arabian date farm. “In most of the environments we’ve gone to we’ve found new species,” he says. “Each environmental niche has its own community of different microorganisms that have evolved to live there. The reason Streptomyces produce antibiotics is that, unlike most bacteria, they’re nonmotile. They can’t swim away from incoming danger. Or swim toward anything that is attractive. They just sit there. They’re sedentary organisms. And to defend their microenvironment, they produce antibiotics to kill any competing organisms in the immediate vicinity.”

Dyson had just returned from Northwest China, hoping to pluck new Streptomyces species from the area’s extreme soils. Quinn took on the challenge of getting the finicky microbe to survive life in the lab. “So I tried to mimic the conditions of the desert. I was like, OK, hot in the daytime, cold at night.” By day, he stored the bacterium in a 113-degree incubator; by night, a room at 39 degrees. In time, the Streptomyces thrived.

That experience set him thinking about Boho’s dirty little secret. He knew that Streptomyces can often be found in inhospitable settings, like alkaline lakes, or caves. He also knew that the Boho region was one of the few alkaline grasslands in Northern Ireland. “I thought, ‘It has special plants, special limestone plants, special mountain plants.’” He wondered if the area had specialized organisms as well. When he went home on holiday, he took a couple of samples from the surrounding hills.

Then, while visiting an aunt, he asked, could he test some of her clay?

“There’s stuff in a grave,” she said, cryptically, meaning the McGirr site.

“Grave? Nah. That’s one step too far: It’s a bit spooky.”

He soon reconsidered. “I thought, ‘Why not? I’ll take some with me to Swansea and see.’”

Back in the lab, a special protocol was used to isolate what turned out to be eight strains of Streptomyces from the Boho soil. Luciana Terra, a team member from Brazil, then went on to the next step, pitting the Streptomyces against some common pathogens. Eventually, the genomes were sequenced by growing each individual bacterium on a separate agar plate, extracting the DNA, reading the DNA fragments in a sequencer and comparing the sequence with known Streptomyces strains.

The new strains were then cage-matched with superbugs. To the research team’s surprise, the strain inhibited both gram-positive bacilli and gram-negative, which differ in cell-wall structure; the gram-negative are generally more resistant to antibiotics because of the relative thickness of their cell walls.

But what to call the new bacterium? Owing to its sweet, woody, wintergreen oil-like aroma, Quinn suggested the not-particularly-lyrical Streptomyces Alkaline Fragrance. A friend suggested myrophorea, a Greek-derived name for the myrrh-bearing women in the New Testament who found the tomb of Jesus empty after the Resurrection. “The Myrrhbearers were known as ‘The Carriers of the Fragrance,’” Quinn explains. “What could be more fitting?”

After Terra had processed the samples, Quinn, on his next trip to Boho, dumped what remained of the soil back onto Father McGirr’s grave. “Sure, I’m a scientist,” he says, deadpan, “but why take unnecessary risks?”

* * *

The current model for antibiotic development is in shambles. Due to meager profits and regulatory hurdles, legacy drug companies have largely abandoned research in the field, complain scientists confronting this issue. To bring a new drug to market typically requires an enormous outlay of time (10 to 15 years) and money (perhaps even upward of $2 billion). Unlike medications for chronic conditions like cancer or diabetes, most antibiotics are used for relatively short periods and are often curative. That might not matter if prices were high, but they’re kept low throughout the developed and developing worlds, which tamps down incentive for pharmaceutical firms to come up with new agents. Last year alone, three Big Pharma outfits shut down their antibiotic programs. The few that are left—Merck, Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline—often wind up vying to create compounds for the same infections. Given that bacteria can quickly develop resistance to a new antibiotic, public health experts recommend prescribing as little as possible. “Any new antibiotics must be managed very, very carefully if you want them to be useful, not just now, but in 10 or 20 years time,” Dyson says. “There’s not an appealing business plan for pharmaceutical companies—obviously they want to sell as much as they can within the patented lifetime of that antibiotic. So, in this context, good old capitalism doesn’t necessarily help mankind or our health.”

Which is why he and Quinn, hoping to keep their research going into the future, will pursue funding from nonprofits that don’t face pressure to constantly generate earnings. Not that they’re opposed to getting underwritten by one of the Big Fish. After all, Dyson notes, there is precedent for this. “Some major pharmaceutical companies waived their royalties in order to produce and distribute ivermectin for the treatment of river blindness and lymphatic filariasis.”

For Julian Davies, financial backing has proved as elusive as the slipperiest of microbes. Davies, a British microbiologist, mentored Dyson at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and leads a Canadian team that uncovered potent antimicrobial activity in a glacial clay deposit found off Kisameet Bay in British Columbia. The fine, pale-green clay has been used for many generations by the Heiltsuk First Nations people to treat burns, diabetes, arthritis and psoriasis.

In 2011 the Heiltsuk signed an operating agreement to allow a non-Heiltsuk company to harvest the clay, now branded as Kisolite, for commercial use. Davies was asked by the firm, Kisameet Glacial Clay, to study the clay’s antimicrobial properties. To Davies, it sounded like quackery. It wasn’t. In lab experiments, Davies and his team developed an experimental extract powerful enough to wipe out all 16 strains of bacteria tested, including superbugs. Davies says the clay has also demonstrated the ability to combat Mycobacterium ulcerans, a debilitating skin infection. But the company has stopped bankrolling Davies’ research and seems to have decided to harvest the clay mainly as an ingredient for cosmetics. (Kisameet Glacial Clay did not respond to inquiries.)

As for the work begun at Swansea, after Terra, Dyson, Quinn and colleagues announced the discovery of their “novel Streptomyces” in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology last year, the task of identifying the precise, pathogen-busting compounds produced by the newly identified bacterium lies ahead. “We have narrowed down to one or two candidates,” Quinn says. But funding remains an obstacle for this crucial next phase. “The research is still operating on a shoestring,” Quinn acknowledges. “I also work half the time at other jobs to keep afloat.” Having spent much of the summer and fall writing grant proposals, he now says that “there may be a company in America starting to take an interest.”

Meanwhile, Quinn continues to roam the hillsides, whenever he happens to be home, on the hunt for breakthrough antimicrobials. “I have isolated a new species from soil higher up the mountain in Boho, maybe a mile from our churchyard site,” he says. “The new species is inhibitory to gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, and to yeasts as well, which is quite unusual. We will be doing lots of tests on this species and trying to sequence it.”

* * *

Dessie McKenzie, a hospitable Irishman, pours a wee dram of a tawny, single-malt whiskey for a visitor from America. The bar at the Linnet Inn is empty, the door is locked; dust hangs in the air reflecting the afternoon sunlight and echoes of silence rattle in the corners.

News of the discovery of the McGirr soil’s antibacterial potency prompted a dramatic rise in pilgrims to Sacred Heart Church, he says. A woman, so the story goes, arrived at the churchyard with a pillowcase draped over her shoulder. “She intended to fill it up and scatter the soil over the grave of a dead relative,” McKenzie says.

I add: “I’ve been told that someone showed up looking for enchanted soil to heal a sick dog.”

He replies, sighing heavily: “Sadly, not true. I heard it was a sick cow.”

One out-of-towner had asked McKenzie if she needed to swallow the soil to “get the full medicinal benefits.”

“I had to say, ‘No, no. We definitely don’t eat it!’”

“Oh, but I hear the cure works miracles,” the visitor insisted.

With an even heavier sigh, McKenzie recalls, he counseled: “Ah, right then. Here’s what you’re supposed to do...”

If there’s one thing he’s learned, it’s never to treat soil like dirt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/19/fe19c5bc-9677-48e3-b1c5-7bde84e9fbe9/pharmamobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/56/1056bb74-842d-4ff1-ae21-2d392d29e9ea/pharmaopener.jpg)