Heartbreaking Photos of Children Who Are Risking Everything to Reach the United States

Michelle Frankfurter tells the stories of these young migrants and also those of the thousands who jump aboard “the death train”

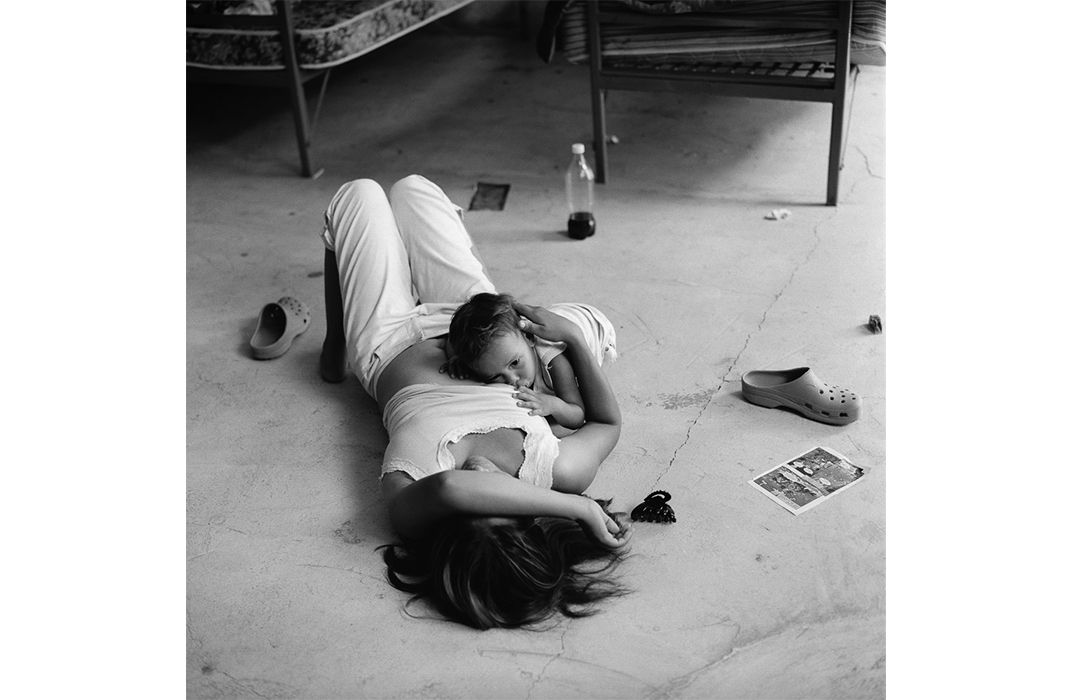

Why would a 53-year-old award-winning photojournalist with a successful wedding photography business leave the comfort of home and take risks that would endanger her life and well-being? A humanitarian crisis that has led to 47,000 unaccompanied children to be apprehended by U.S. border security in just the past eight months. Michelle Frankfurter has turned her concern and her camera to document the dangerous journey many young, aspiring immigrants from throughout Mexico and Central America take to better their lives and escape the extreme poverty of their home countries.

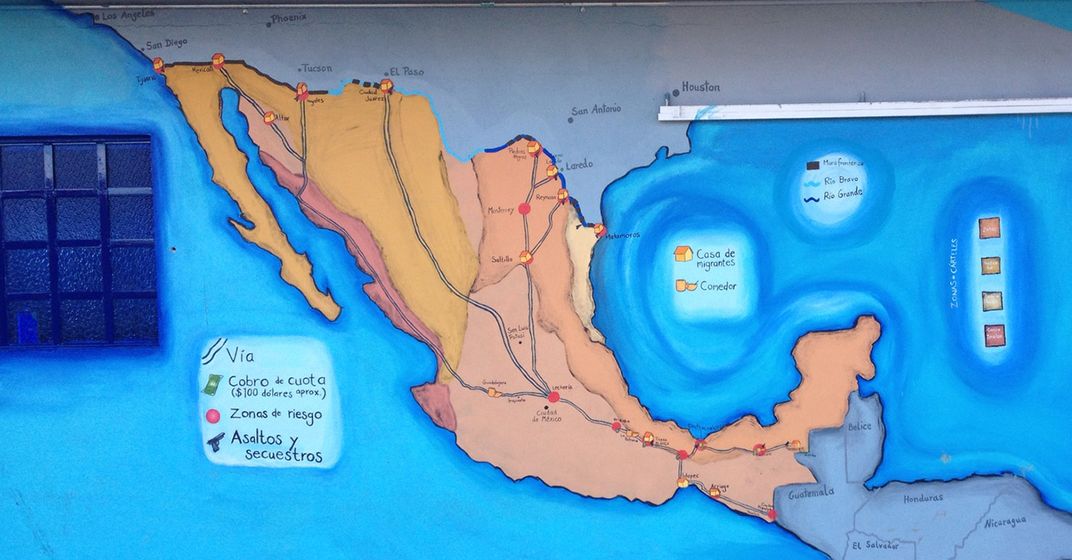

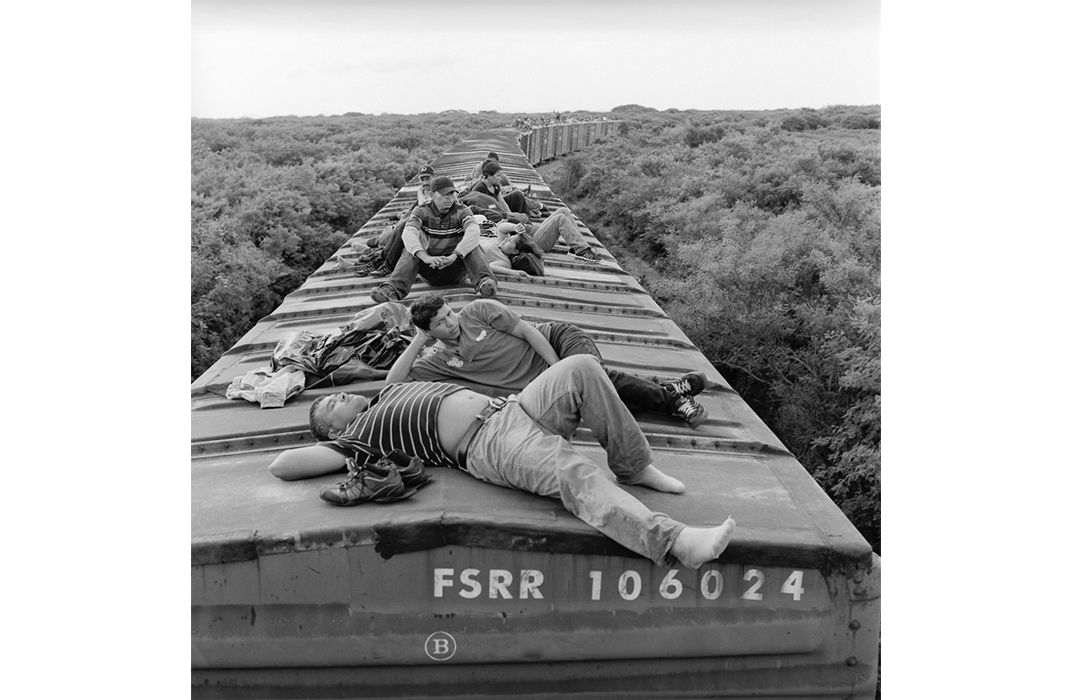

For eight years, Frankfurter has accompanied youths on freight trains, commonly referred to as the “death train” or la bestia because so many travelers do not survive the trip. Originating in the southern Mexico town of Arriaga, the migrants, many of whom have illegally entered Mexico from countries further south such as Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala, take various freight routes that lead to the border towns of Cuidad Juarez, Tijuana, Laredo, Piedras Negras and Nogales. Those who board in Arriaga, can simply clamor aboard up ladders while the train is in the station and sit on top of the train. This is where Frankfurter would begin her trips. Further along the way the train must be boarded while in motion. Many people slip, lose their grasp and fall under the train. Others fall asleep while underway and fall off the train. Sometimes criminal organizations like the Zetas try to extort money from the migrants at various points along the trip and push them off the train if they don’t pay.

Frankfurter, who once described this project as part of her “amazing midlife crisis”, has created a collection of startlingly beautiful and empathetic images of families and children, some as young as 9 years old, traveling alone. She sees her subjects as brave, resilient and inspiring and is producing a book of these images called Destino, which can be translated as either “destination” or “destiny.”

Inspired by the epic tales of Cormac McCarthy and other authors, Frankfurter has been photographing in Mexico for years. In 2009, her interest was piqued by Sonia Nasario’s Enrique’s Journey, the story of the Central American wave of immigrants from the view of one child.

“The economy was still limping along and I didn’t have much work booked,” says Frankfurter. “I found myself having the time, a vegetable bin filled with film, some frequent flyer mileage, and my camera ready. Beginning this project, I felt like I was falling in love. It was the right time, right place and right reason. I felt I was meant to tell this story.”

I spoke with Frankfurter in-depth about her experiences on the train.

On the books she had been reading:

“I was infatuated with these scrappy underdog protagonists. I grew up reading epic adventure tales and the migrants I met fit this role; they were anti-heroes, rough around the edges but brave and heroic.”

On why she took on the task:

“It was a job for perhaps someone half my age. But I also felt that everything I had done prior to this prepared me for this project. I feel a connection to the Latin American people. I had spent time as a reporter in Nicaragua working for Reuters when I was in my 20s. In a way I became another character in the adventure story, and I added some moments of levity to the journey just by the improbability of being with them. Somehow I made them laugh; I alleviated some difficult situations, we shared a culturally fluid moment. I was very familiar with the culture, the music, the food the language, and so in a way, I fit right in, and in a way I stood out as quite different.”

On the challenges these migrants face:

“The worse thing I experienced myself was riding in the rain for 13 hours. Everyone was afraid that the train would derail, the tracks are old and not in good condition and derailment is common. Last year, there was a derailment in Tabasco that killed eight or nine people”

“I felt I had a responsibility to collect their stories, be a witness to their lives and experiences. Overwhelmingly I got the sense that, even in their own countries they were insignificant, overlooked, not valued. When in Mexico, it’s even worse for the Central American immigrants, they are hounded and despised. They are sometimes kidnapped, raped, tortured or extorted. Local people demonstrate to close the shelters for the migrants and the hours they can stay in the shelters are often limited to 24 hours, rain or shine. When and if they to make it to the United States, it’s no bed of roses for them here either.”

On re-connecting with some of her subjects:

“I recently connected on Facebook with a family and found out that they settled in Renosa (Mexico), they gave up on getting to the U.S., at least for now."

“I met one person in a shelter in a central Mexico; later he had lost everything along the way except for my business card. He showed up on my front lawn in Maryland one day. He had no family in the U.S., it was when the recession was at it’s deepest and there was no work. I helped him and he helped me. I taped his stories for the record, and I found him a place to stay.He shared some of the horrors of his experience. Once he and a group of migrants in a boxcar almost asphyxiated when a fire they made for warmth got out of control and consumed the oxygen in the car. Other times the migrants could barely walk they were so stiff from a long and dangerous exposure to cold.”

On how she stayed safe during her journeys:

“I stayed in shelters along the train line and when I had a good group, I asked to go along. In the shelters people live dormitory style, it’s a bit like college, sharing stories and thoughts about life, the future. We are social animals, people like to listen and share life stories. We’d sit on Blanca’s bed and share “la cosas de la vida.” When I traveled with a group, we were a bonded group. People form coalitions based on mutual needs. And friendships are formed quickly because the circumstances are so intense. My decision to travel alone, not to take a fixer or travel with anyone but the migrants was a good one. People opened up to me more, related to me more, we were doing this thing together. They realized I was interested in their lives, I cared and I identified with them. They were happy to have me along, I was welcome.”

On how to solve the crisis:

“The United States can’t fix all these things, the responsibility for fixing lies with the countries [such as Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador] themselves, but we can help. And we should because indirectly we do bear responsibility. Our society uses and is interested in cheap labor, and cheap products, this is our relationship with these countries for years, so in a way we are conflicted about changing that system. Global corporations take advantage of the fact that there is little or no regulation, lots of cheap labor and no protections for workers on top of that. Then if circumstances change, on a whim companies will move and destabilize an entire area. Then people have no option but to migrate, with factories closed there are no other options. Add to the mix, criminal organizations selling drugs, guns, trafficking humans and wildlife, and you can understand why people need to leave.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/b6/70b64c4c-bcc7-4da1-a1c9-240dc67db0df/2mfrankfurter_destino02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/38/4c38705c-d714-429a-bb79-47c9b155f86f/3mfrankfurter_destino07.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/af/5baf3b2e-e3ea-4a8b-8ddc-cf062ce6ae3a/4destino_kids06_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/8a/ec8a0266-44d8-48f3-90fe-377fe4e2021a/5destino_kids02_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/56/6556db8f-b963-46be-afd0-5837d5be12d0/6destino_kids11_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/1c/a91cf791-a78e-477b-bc40-d47ad0af59fe/7destino_kids07_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/a9/f6a92f38-6693-4c24-8e3f-0fc877d9d8aa/10destino_kids12_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/c1/22c1c283-2af1-4b82-a97a-0b8d91734ff7/9mfrankfurter_destino10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/f3/fbf3d877-5ca0-4ae6-8b02-7cf1ad544fc0/11mfrankfurter_destino03.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/24/bc244056-8043-4fc3-ad88-7c421b09a4d6/12mfrankfurter_destino08.jpg)