The World’s First True Artificial Heart Now Beats Inside a 75-Year-Old Patient

The two-pound Carmat heart quickens or slows blood flow based on a person’s physical activity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/5b/e65b179c-50b6-4b2c-a999-d3571f7ea871/artificial-heart-large.jpg)

A 75-year-old Frenchman has just been given the gift of life as a team of surgeons have successfully completed the transplant of a revolutionary artificial heart.

The patient, so far unnamed, is reportedly recovering at Georges Pompidou European Hospital in Paris, where the 10-hour long operation was performed last Wednesday. Unlike similar devices used to keep patients alive until a donor can be identified, the "Carmat" heart is expected to operate continuously for as long as five years while enabling the recipient to resume a normal lifestyle, perhaps even allowing the person to return to work.

“We’ve already seen devices of this type but they had a relatively low autonomy,” Alain Carpentier, inventor and surgeon, told reporters, according to The Telegraph. “This heart will allow for more movement and less clotting. The study that is starting is being very closely watched in the medical field.”

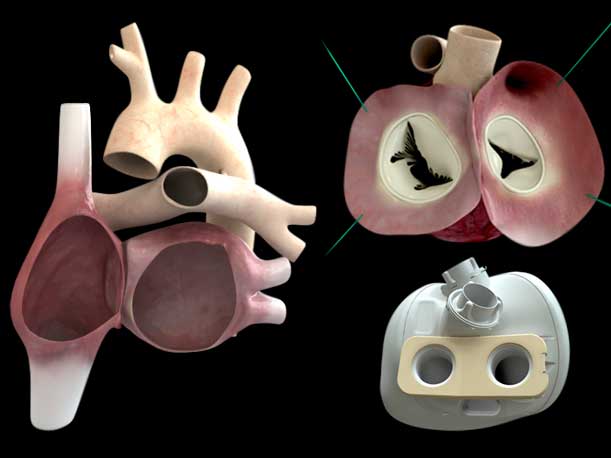

Thousands of heart implants have been carried out, but Carpentier says the version he developed was the first to fully replicate the self-regulated contractions of a real heart. Inside the two-pound mechanical organ is an intricate system of sensors and microprocessors that monitors the body’s internal changes and alters the flow of blood as needed. It quickens or slows the blood flow based on the person's activity. "Most other artificial hearts, by contrast, beat at a constant unchanging rate. This means that patients either have to avoid too much activity, or risk becoming breathless and exhausted quickly," writes Gizmag. On the outer surface, the synthetic organ is partially made of cow tissue to reduce the likelihood of complications such as blood clots, which are common when fabricated materials come in contact with the blood. Patients who receive artificial heart transplants usually take anti-coagulation medication to minimize such risks.

The technology, which took 25 years to develop, started taking shape after the surgeon initially tested the feasibility of developing artificial heart valves using chemically-treated animal tissues as an alternative to plastic. Since then, he has obtained approval from authorities in France, Belgium, Poland, Slovenia and Saudi Arabia to conduct human trials that are expected to run until the end of 2014. If all goes well, meaning if the patients survive at least a month with Carmat systems, Carpentier will then have the means to seek regulatory approval to make them available within the European Union sometime in early 2015.

Ultimately, the litmus test hinges on whether the artificial heart's pumps last more than a few years. Barney Clark, the world's first heart implant patient, survived only 112 days following a milestone procedure in 1982 that replaced his failing heart with the man-made Jarvik-7 heart. The SynCardia total artificial heart, which remains the only FDA-approved heart replacement option, has made it so that patients carry on much longer, though they'd have to adjust to the burden of "carrying around a compressor and having air hoses going in and out of your chest," says heart surgeon Billy Cohn in a CNN report.

The Carmat artificial heart is designed to mimic the dual chamber pumping action of a real human heart. Credit: Carmat[/caption]

Carpentier's half-cow, half-robotic technology takes a different approach, as compared to SynCardia's air compression method, in utilizing a hydraulic fluid to facilitate the movement of blood. A comprehensive report in MIT Tech Review explains how this mechanism works:

"In Carmat’s design, two chambers are each divided by a membrane that holds hydraulic fluid on one side. A motorized pump moves hydraulic fluid in and out of the chambers, and that fluid causes the membrane to move; blood flows through the other side of each membrane. The blood-facing side of the membrane is made of tissue obtained from a sac that surrounds a cow’s heart, to make the device more biocompatible. 'The idea was to develop an artificial heart in which the moving parts that are in contact with blood are made of tissue that is [better suited] for the biological environment,' says Piet Jansen, chief medical officer of Carmat."

The device, powered by rechargeable lithium-ion batteries and worn on the outside, is about three times heavier than a human heart, which will limit its compatibility to 86 percent of men and 20 percent of women. However, Carpentier plans to develop smaller versions for women of smaller stature.

The Carmat artificial heart is expected to cost about 140,000 to 180,000 Euros (or $191,000 to $246,000).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)