Coming to Terms With One of America’s Greatest Natural Disasters

Documentary filmmaker Bill Morrison plunges us into the Great Flood of 1927

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/c8/8bc8d753-c5a3-42ec-b7f0-1a6faecee5f6/nov14_n02_billmorrison-main.jpg)

Prologue

The beginning is the river.

The river fills and empties a continent

this river is time,

a river of men and women.

This river is the story of a world

erased, a river widened and bent and widened again,

bearing away the past and carrying the future at the end

of one America and the beginning of the next.

In this tin roof America long gone—unreckoned and

unlamented, sunk to the rafters in fast black water,

chimneys awash and every coop and furrow submerged—

is the drowned history of our original American sin.

We inherit its memory, its muddied antiquities, the

inventory of its miseries, its fertile earth, its alluvial

stink, its cause and its consequence. We are its heirs, its

debtors, its bankers, its children. We inherit its dead.

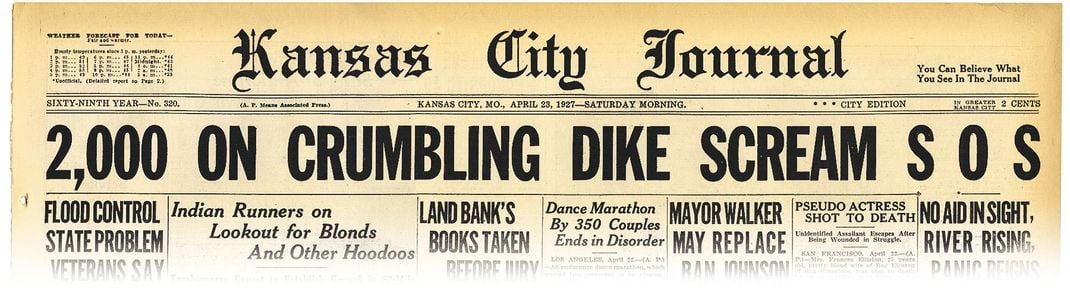

So the news of it came and went and was left to lie

in a thousand morgues at a thousand papers, or filed in the

dying libraries, or recorded on film that was itself doomed

to decay and condemned to silence.

Overtaken. Forgotten. And yet. And yet. And yet what comes to

us now, what maybe saves us, is somehow art and somehow

grace, somehow time and out of time, a documentary not a

documentary of our ruined and ruinous living age.

Images and music without nostalgia, without sentiment,

without regret or false hope, hypnotic and soothing, our

panic and cruelty and the Jim Crow universe of our violent

helplessness just at the edge of every boiling frame.

A movie made of ghosts, a new moving art of the living and

the dead, the past and the future, of history

painted by an artist, by Bill Morrison,

that feels like a new way of seeing.

The music is a bright, narrow horn and dire guitar,

elegiac, strange, a dirge for bucket and shovel,

major and minor, as avid and dark at the margins as the

pictures it underlines and transforms.

It may be the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen.

That was the Great Flood.

This is The Great Flood.

That was 1927.

This is 2014.

I

Spring, summer and fall of twenty-six the rain fell and

falling filled the rivers and streams and creeks and the

sleep of the farmers and the dreams of their children until

fear and the earth were everywhere fat with water.

And on and on it rained through winter and spring

from the top of America to the bottom, west and east

and at every point of every compass came the rains and the

rivers rose in the red-brick river towns and the water

poured down on the fields and the hollows and the hills,

the mountains and the valleys, and the rivers rose month

upon month and the rain and the water raced South

There were giants in the earth in those days

and the water poured out of the forests and out of the

orchards and into the creeks and the streams and down the

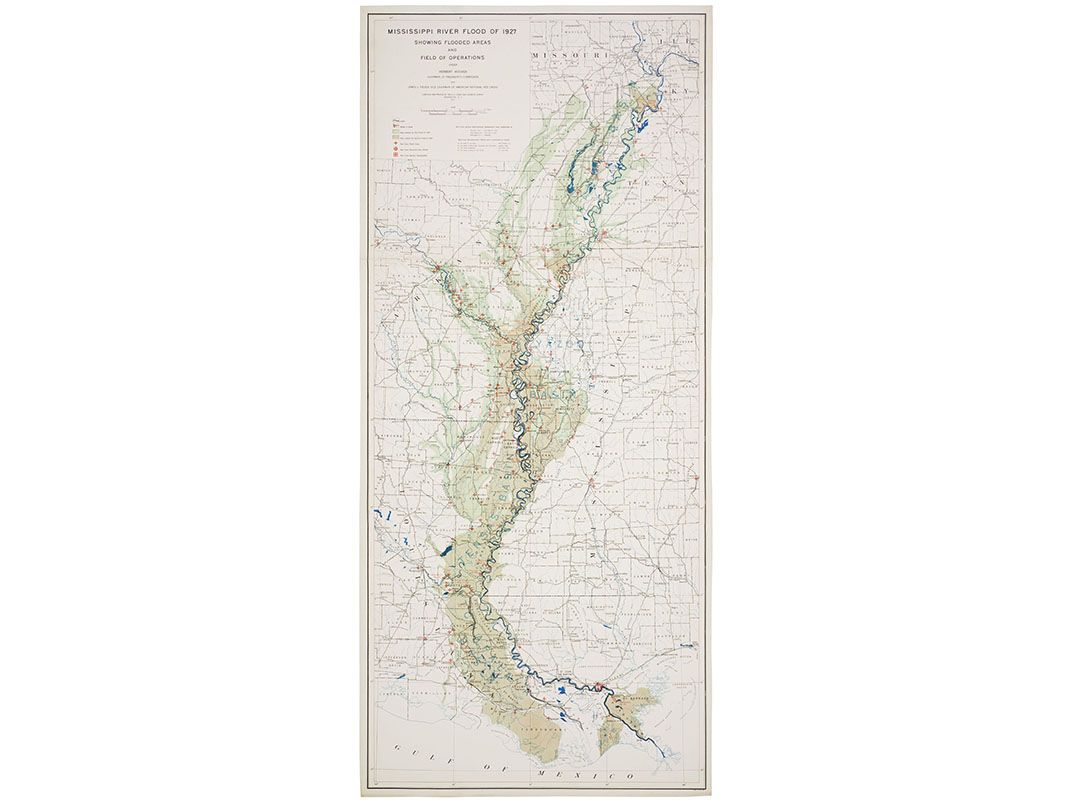

Ohio and the Alleghany, the Missouri and the Monongahela

And the earth was filled with violence

and everything everywhere under the window of heaven

was green and lush and terrifying, until all the water in

the world rode fast and hard against the banks of the

Mississippi, hard and fast against the levees and the

bridges and the lives of everyone from Cairo to New

Orleans. From Illinois to the Gulf, Shelby County to St.

Bernard Parish, from New Madrid to Greenville to Vicksburg,

Yazoo City to Hamburg to Baton Rouge, the river rose.

This is time out of time, in what seems an ancient age

of black and white, of mute brutality, of poverty and

struggle and squalor, of joys and lives too small, too short,

as near as our own, as distant as the Old Testament.

Then the levees broke.

II

250 dead in April? 500? By May, 900,000 homeless? No one

is sure. The flood is 50 miles wide, 17 million acres of the

American South and the clichés of the American South sunk

to the ceilings. A wide world lost, smothered, swept away.

Months under water, months under that heartless

sun, months under the abject moon, long nights like

Old Egypt, the days all dazzle and glare from horizon to

horizon. The backhouses and smokehouses and the

sheds, the silos and the cribs and the troughs and the pens

and the tanks and the shacks, the cows and the mules and

the cities and the towns and the people suffocating in the

muddy flux of the river.

Every candle stub and lantern, chifferobe and skillet,

every house on every street, the scales and the gin and the

broker, the owner and the banker and the churchman, all

sinking in a lake that runs from Missouri to Louisiana.

Bundled on the high ground are the useless sandbags and the

bedsteads and the quilts and the pots and the pans and the

dogs and the cattle and the families, a long rank of tents

and refugees on an archipelago of levee tops.

The newsreels tell us so—the ones remaining in the

archives and libraries, those brittle nitrate spools

moldering and decomposing, oxidizing, turning to dust,

to jelly, to fire. This is how Morrison loads his palette.

III

Chicago-born, a painter by training and inclination

Morrison began studying animation,

sampling images and making short

films in the early 1990s

for a theater company.

Now he sources and assembles his films

from fragments found in the Library of Congress

and at the flea markets

and at the

University of South Carolina,

digitally scanning each crumbling,

silvering image before

it bursts into flame,

that nitrate base the unstable, explosive,

first cousin to

guncotton.

Historian as art historian as artist, painter as film maker

as archaeologist

as auteur

and editor of decay.

“Just don’t call it experimental film. The experiment is

over.” The worldwide prizes and awards, the

fellowships, the

Guggenheims, agree.

He is slender and sharp-featured,

well-spoken, modest. (His next project

will be made from fragments mined

from underneath that Dawson City ice rink,

where you heard they found the Black Sox footage

from British Canadian Pathé,

and a hundred years worth of

rusting, swollen film cans.)

Composer Bill Frisell

is modest too and too quiet

and maybe the best

jazz guitarist alive.

“I get everything I need out of music,”

he says, and the music

gets everything it needs

out of him.

They met 20 years ago at the Village Vanguard

in New York City—when Frisell was booked

to play guitar, and Morrison was in the kitchen

washing dishes.

Morrison made it out, made more movies,

worked with more composers—

Philip Glass and Laurie Anderson,

John Adams and Jóhann Jóhannsson,

Wolfe, Gorecki, Douglas, Lang,

Iyer, Bryars, Gordon—

drawing his film from

everywhere

The Great Flood

is best seen live

on a stage with musicians and a wide white screen

bounded only by your expectations.

From the languid dread of the opening aerials

it challenges what and how you see and think and feel.

Like a narcotic.

Like a dream.

IV

The lost. The riddle of Man and Woman trapped

not in The Garden,

but on the

roof of a car sliding away in the swell

as businessmen vote

to dynamite the levees

to save New Orleans, and politicians tour the calamity

on camera, smiling, pointing

and smiling, children in the shallows

and a piano on the shore among

the chickens and Herbert Hoover in his celluloid collar,

and you think of what folks thought as the water rose—

that the chip in this old pitcher is the last thing I’ll

ever see, this earless ewer, this can, this dipper and the

yellowing curve of my own fingernail may be the last

things I’ll ever see

of Nature’s great unmaking, the undoing mother, the loving

hand smothering the world. Stillness and erasure and then

nothing, finally nothing, beginning and ending

but never ending,

deciding what abides and what cannot abide

in this place, death rising through the floorboards and

Life, its teeth sunk in you, insisting on itself, always

itself. Those are the stakes.

So maybe somewhere someone hears a voice and that voice is

the Voice of God (but not the voice of god), so the unknown

Noah never comes and there is no hope but the hope of your

own voice, a climb to the roof and a long song of despair.

Both man, and beast, and the creeping thing and the

fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made

them. In testimony to the bitterness of His failure

was the drowning of the first world in the leaden

waters of His anger, of every corruption sunk and

suffocated by His silence and His tears. He could not raise

us, so he held us under. Where are the birds? Where is the

rattle of the branch? The rustle and the melody?

Sandy and Katrina, serial killers

with spring break names; Gilgamesh;

Ophelia in Atlantis,

the cleansing never cleans.

Imagination enslaves us all,

film and art insistent

on themselves, demanding

you see and think and feel. Now consider

the man you can’t see,

the one behind that big box camera, cranking, his cap

turned backward (if that helps you to see him)

cranking like a clockworks, sweating,

how did he even get here?

With that immense wooden camera

on that impossible tripod

heavy as a coffin?

His film goes back to Memphis, Nashville—maybe

Little Rock has a lab—on a boat, in a car, on a train,

then Chicago or New York, cut and spliced and shipped

to every Bijou and Orpheum from Khartoum to Bakersfield.

The violence waiting a foot or two offscreen, the brute

and casual fascism, the race hate and the cops

and the tangle of human complication tightening in the

water like a knot.

(This country was never

light with the lash

or

the nightstick)

Folks just like us / not like us. Low blues and dry horn,

guitar like an accusation, vibraphone, flatboat and

National Guard, sodden hatbands and a little girl on the

roof. Hand-painted neckties, watch pockets and

live oak, Sears Roebuck and Model-T,

cast iron and canvas and black folks

put out on the levees and in the wallows,

living in the freight yards, waiting.

Another wave for the Great Migration,

the long escape to prosperity,

to the foundries and factories and

slaughterhouses of the North,

back when it felt like people were connected to

nothing but each other. Where is the monument to their

courage? In this music. Where is their memorial?

Here.

V

Morrison frees us from Hollywood

tropes and

disconnects images from narrative

images from sentimentality

images from cliché

images from time

until we give up making sense

and simply see

and feel our part in the long parade,

welling with a kind of optimistic melancholy

as the world unfurls

the strange peace that comes of destruction

his patience rewarding patience in

Light is Calling

a film too ravishing

to understand

or The Film of Her,

in which

the intensity of his vision

becomes your own.

Just Ancient Loops can be found online,

a video version with cellist Maya Beiser,

machine age music by Michael Harrison

played live

as the spheres and stars spin and

burn in their course,

and their shadows

flicker on the screen.

All Vows, The Mesmerist,

The Miners’ Hymns and Trinity,

Tributes-Pulse and Dystopia,

Outerborough and Fuel,

works of art as much Lumière as Jackson Pollock,

the Josephs Mitchell, Campbell and Cornell,

equal parts Ionesco

and Tod Browning.

His mid-career retrospective

at the Museum of Modern Art

opened in October. Bill

Morrison is 48 years old.

As he redefines

what film is or what film is not

the downtown avant-garde say

that music is too musical

to be truly avant-garde

(the cutting edge

must only be admired,

never liked).

If Morrison is a marvel of ingenuity,

his first masterpiece,

Decasia,

is a work of genius.

The dervish

the geisha in the sea of decay

the desert caravan and the wet deck

of the submarine

in the hot whirlwind

of nitrate rot

and the heavenly discord

scored by Michael Gordon.

Living oxidation

chains of bacteria, thumbprints

and the Rorschach blots of corruption

nuns and cowboys

a fighter

shadowboxes

a column

of blight, jabbing

and feinting

the nothingness

the invisible

the inevitable.

It is a perfect piece of work,

of which director Errol Morris

said, “This may be

the greatest film ever made.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/98/299807f0-a3e2-40c5-91b4-2493e952852c/nov14_n05_billmorrison.jpg)

VI

And now The Great Flood.

History not history

documentary not documentary—

instead, absolution, relief from meaning, a poem.

After twenty-seven came the TVA

and Evans and Agee and

the high art

of poverty.

The Flood Control Act of 1928

rewrote the river and helped make

Hoover president, and in the end

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spent billions

to straiten that same river,

until it poured out

78 years later

into the 9th ward.

Postscript

How it is with us now is how it was with us then

when all the waters of the north became all

the waters of the south. There is a Great Flood

for every one of us,

for every culture,

in every age a scourging story of unreasoned punishment

and death and relentless life. A history of how living clings

to living in our ecstatic tragedy.

This was a long time ago in a different America, a narrow

and unreconciled America that couldn’t last but did,

rotten and untenable, and in the end and at the beginning

the water must always do its work,

as we pour out the daily measure of our vanity

and forgetting, every generation foundering,

the warnings lost, forever

helpless against ourselves.

All of us one day washed away, each carried off by time

and history, not on the river or across it, but part of it,

that endless river of souls lined on its widening banks

with every kindness and sorrow we’ve ever known.

That was 1927.

That was the Great Flood.

This is 2014.

This is The Great Flood.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)