Witness to History

The first memoir by a White House slave recreates the events of August 23, 1814

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Paul-Jennings-descendants-White-House-631.jpg)

The Tale of Dolley Madison’s rescue of the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington is known mainly through Dolley’s own letters and diary. But another firsthand account, by Paul Jennings, a slave who served as President Madison’s footman, is getting new attention. Beth Taylor, a historian at Montpelier, Madison’s Virginia estate, arranged for nearly two dozen descendants of Jennings to view the painting at the White House this past August.

Jennings believed misperceptions had arisen over time. “It has often been stated in print,” he recalled years after the fact, “that when Mrs. Madison escaped from the White House, she cut out from the frame the large portrait of Washington...and carried it off. This is totally false.” Jennings continued: “She had no time for doing it. It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were...expected every moment.”

Jennings said White House staffers John Sioussat, a steward, and Thomas McGraw, a gardener, removed the canvas “and sent it off on a wagon, with some large silver urns and such other valuables as could be hastily got hold of.”

Jennings had come to the White House in 1809, at about age 10, from Montpelier. Dolley kept Jennings until 1846, when, by then an impoverished widow, she sold him to Pollard Webb, an insurance agent, for $200. Six months later, Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster purchased Jennings’ freedom for $120, an amount Jennings agreed to work off as Webster’s servant. In 1851, Webster recommended Jennings for a job at the Pension Office. In 1865, his recollections were published in A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison—believed to be the first published account by a White House slave as well as the first White House staff memoir. But it attracted little notice.

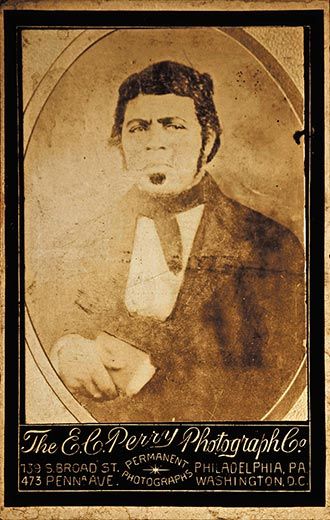

Taylor has unearthed the only known photograph of Jennings (who died in 1874) and discovered details of his marriage to Fanny Gordon, a slave on the plantation next to Montpelier. “It was the [Jennings] memoir that inspired me,” Taylor says. She plans to complete a book about him this year.