The Whiskey Wars That Left Brooklyn in Ruins

Unwilling to pay their taxes, distillers in New York City faced an army willing to go to the extreme to enforce the law

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/3b/6f3b6946-b603-419b-8197-8733a5461993/sf31764.jpg)

It looked like a storm had swept through the industrial Brooklyn neighborhood of Vinegar Hill. Whiskey ran through the cobblestones and pooled near the Navy Yard gate. Alleys were strewn with rocks, coal and scraps of wood. Molasses stuck to the streets and the air reeked of sour mash. The remains of some 20 illegal distilleries lay in ruin for all to see, abandoned in mid-production like an unfinished feast.

It wasn’t a hurricane or an industrial explosion. It was a raid ordered by the newly formed Bureau of Internal Revenue, the precursor to the IRS.

Two thousand soldiers had just attacked the neighborhood, targeting moonshiners who were evading taxes on a colossal scale. Since the federal government couldn’t exactly audit the underground operations, it demolished their operations. That morning, November 2, 1870, battalions under the command of Colonel John L. Broome arrived by boat from nearby forts. Guided by the revenue assessors, they left the Brooklyn Navy Yard at 9am and marched through the narrow streets armed with muskets, axes, and crowbars.

It was the latest in a series of raids known as the Whiskey Wars. Illicit distilling had become so widespread, and gangs so violent, that revenue officials and cops needed military backup. One of the first “battles” came in October 1869, when100 army veterans found nine stills after a knife-and-fist fight in an alley. Its success led President Ulysses Grant to authorize more forceful raids, using the army and navy if necessary. The next battle, at dawn two months later, included 500 artillerymen, who landed on the East River by tugboat and wore white-ribbon Internal Revenue badges. They axed barrels and spilled the contents, gushing a stream of rum into the street. Tubs discovered underground were pumped empty. By afternoon they had destroyed stills that could produce 250 barrels of liquor—worth $5,000 in taxes—a day.

This went on for over two years, but with law enforcement on its payrolls, the neighborhood was never taken by surprise. In the November attack, troops marching down Dickson’s Alley, just 50 feet from the Navy Yard gate, were pelted by stones, bricks, and iron bolts thrown from windows. The armed forces tore apart modest setups with just a few tubs of mash and industrial-sized shops like Whiteford’s, which could make 45,000 gallons of whiskey a week. The proprietors, somehow, were not to be found nor were they deterred. When troops returned two months later with about 1,200 troops, the stills were belching again. Even when 1,400 soldiers stormed the district in 1871, they took just one still and no prisoners—clearly the whiskey men were tipped beforehand.

Liquor was legal, but it was heavily taxed. In evading the duty, the Brooklyn distilleries could pocket hundreds of dollars a day. To fund the Civil War, the federal government had taxed alcohol for the first time since 1817. In 1862. it levied a 20-cent tax per 100-proof gallon. In 1865-68 it spiked to $2, equivalent to $30 today. (Now it’s $13.50.) That exceeded the market rate, according to a congressional report in 1866, making the tax patently unjust. It was also an inducement to fraud.

Just as famed agents like Eliot Ness did during Prohibition, post-war revenue officers discovered tax-evading operations around the nation: an illegal distillery in a disused coal mine in Illinois; 30,000 gallons of grape brandy beneath a Los Angeles shed; and primitive stills as far away as Maui. They demolished vats of mash in Philadelphia stables and battled moonshiners in Kentucky backwoods. In a way, this was an existential fight for the federal government. It practically ran on booze: Alcohol taxes provided upwards of 20 percent of its revenue.

As the report recommended, the tax was eventually lowered in 1868 and ranged from $0.50 to $1.10 for the next few decades. The lower tax actually led to increased revenue, but distillers still found it exorbitant. After all, they hadn’t been taxed at all until 1862 so were used to paying nothing. And it was temptingly easy to evade.

These moonshine battles presage the struggles during Prohibition 50 years later. It should have been a cautionary tale: taxing alcohol, like criminalizing it, created an underground industry. The rates were founded on the flawed assumption that businesses and inspectors were honest. Legitimate distilleries stocked up before the tax was instituted, then stopped production almost completely. Small copper stills were suddenly sold across the country. “Vinegar” factories popped up. Local cops looked the other way, leaving the feds to enforce the law.

Oversight was a joke. An agent was to weigh every bushel of grain that came in and note every gallon that went out. One man couldn’t keep track of all of this, and he was easily paid off for miscounting. Some inspectors didn’t even understand how to determine the alcohol’s proof. Nor could officials monitor the output 24 hours a day, so licensed distillers often produced more than their alleged capacity by working at night. In Manhattan, for example, a west side distillery ran off whiskey through a pipe to a nearby building, where it was barreled and given a fraudulent brand—avoiding over $500,000 in taxes in seven months. That’s over $9 million in today’s dollars.

Distillers formed criminal rings, had connections in City Hall and lived like kings. As described in a New York Times the Brooklyn distillers sound like the cast of a Martin Scorsese film:

Nearly all of them wore ‘headlight’ diamond studs, big as filberts and dazzling in their luminous intensity. Now and again you would see a boss distiller wearing a gold watch that weighed half a pound, with a chain long and ponderous enough to hang a ten-year-old boy by the heels. The bigger the watch, the heavier the chain, the better they liked it…Every distiller’s wife and daughter fairly blazed with diamonds.

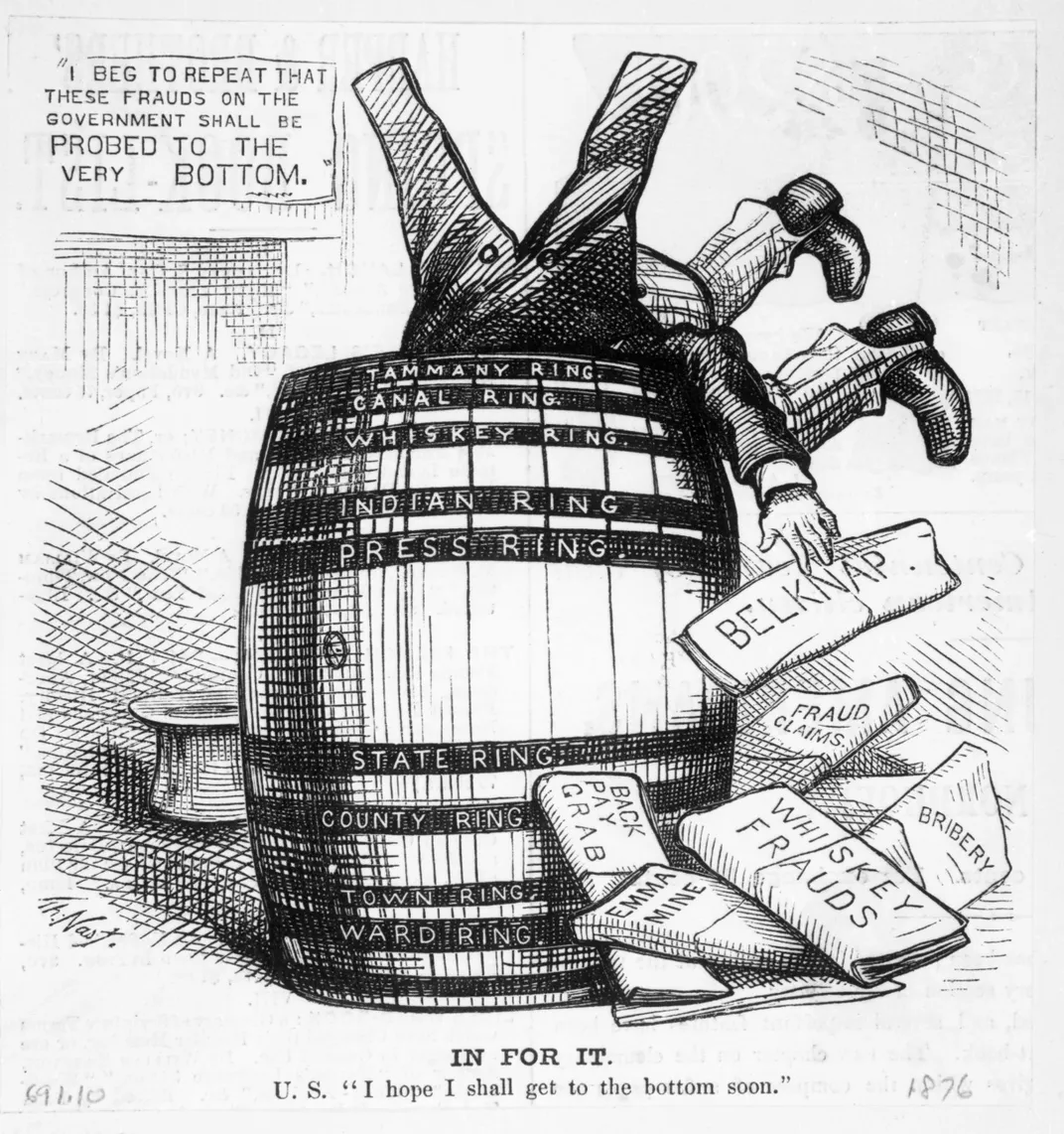

Moonshiners and their cash almost certainly made their way into politics. Allegations of corruption went all the way to the White House. In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant’s personal secretary was indicted on charges of participating in a massive whiskey ring, operating out of St. Louis and Chicago, that bribed revenue officials.

As the country’s busiest port, New York City was central to trade of all kinds, including moonshine. Newspapers often reported the discovery of stills with the capacity of upwards of 100 gallons a day. The distilleries were essentially small factories. In the cellar of an old chapel on Manhattan’s East Broadway, the Times wrote, a two-foot high opening led to a 30-by-40-foot chamber “filled with great black hogsheads and barrels, and, in the red glare from the furnace grate, long coils of black hose stretched from the still-vats overhead and underfoot…The spirits flowed in a steady stream from the neck of the still-worm into a receiving-tub.”

Nowhere in New York so flagrantly ignored the excise as Brooklyn’s Fifth Ward, or Vinegar Hill. Adjacent to the East River docks and the Navy Yard, it was a rough, overcrowded district of small tenements and row houses populated by a flood of immigrants in the mid-19th century. Known as Irishtown (a third of its population was Irish-born), the neighborhood also included many English, German, and Norwegian residents who worked at local factories and warehouses. Immigrants brought with them a fondness for drink; at the neighborhood’s peak in 1885, 110 of its 666 retail outlets were liquor establishments, mostly saloons. This, in turn, likely attracted extra government notice where other groups were able to elide attention. Much of the rhetoric of the ever-growing Temperance movement was directed at immigrant watering holes such as those in Irishtown.

“It will not be wondered why Irishtown was so lively and full of fight” in the years after the Civil War, reminisced the Brooklyn Eagle a few years later, when the Temperance movement had gained even more attraction. “For the entire neighborhood was honeycombed with illicit whiskey stills.” There was rum too, “so excellent and its quantity so extensive as to gain for it the distinctive name of Brooklyn rum,” said the New-York Tribune. Irishtown’s alleys smoked with distillery fumes and stills were hidden in cellars or abandoned shanties, built to be dissembled quickly. Distillers constantly played cat-and-mouse with inspectors and were rarely caught, helped by a spy system and neighbors who circled inquisitive strangers. Street gangs, smugglers and thirsty sailors supported the illicit industry, using the waterways to boost the business. Rum and whiskey were shipped up and down the East Coast; some skips even had distilleries on board. The crowded waterfront made it easy to load ships without detection.

Those in charge were canny figures like John Devlin, a leader of some notoriety who began his career in the Navy Yard. Devlin allegedly attempted to take a 20-cent cut out of every whiskey gallon in the neighborhood and was said to have corrupted the entire revenue department. In true underworld fashion, he was also shot multiple times by his own brother, who landed in Sing Sing.

In a closely watched 1868 trial, Devlin was accused of running a distillery without a license and defrauding the government out of $700,000 in six months. He claimed that he had indeed filed the $100 license but the officer in charge ignored it, and Devlin felt he “should not be held responsible for the carelessness of another.” Devlin ended up being fined a laughable $500 and was charged with two years in prison. The Eagle said it was as if a man stole a million dollars but was charged for not buying a ferry ticket. The trial had been intended to set an example to distillers. After a year in Albany Penitentiary, Devlin was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson.

The Irishtown ring was suppressed only after a revenue official was fatally shot, stoking public outrage and stronger government action. After a final, crushing raid, its distilling industry was largely demolished.

These days, the neighborhood is a lot quieter. But whiskey-making returned in 2012, with the arrival of Kings County Distillery. It makes bourbon from organic corn, rather more precious but perhaps just as distinctive as the famed Irishtown rum. The neighborhood’s ghosts would feel triumphant: The distillery is located inside the Navy Yard.