What You Don’t Know About Ancient Rome Could Fill a Book. Mary Beard Wrote That Book

The British historian reveals some surprises about the ancient Roman people and their customs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/e5/dce58054-38a1-436f-9554-61d3184eec3b/aabr003619.jpg)

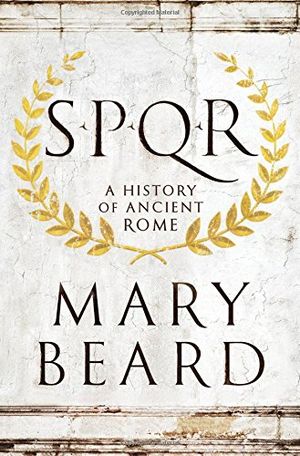

Mary Beard, a professor of classics at the University of Cambridge, is known for her frank and provocative reading of history. More than a dozen books and frequent newspaper articles, book reviews, TV documentaries and a prolific Twitter account have made her one of England’s best-known public intellectuals. She has a new book, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, out this month. We spoke to her by email about Rome’s most interesting characters, best slogans and surprising legacies, including its cutting-edge lavatory design.

The title of your new book is an acronym for a Latin phrase meaning "The Senate and the Roman People." Why did you choose that?

Two thousand years ago it was the instantly recognizable shorthand for the city, and the state, of Rome. And it still is. You see “SPQR” plastered on modern Roman trash bins and street lights. It must be one of the longest-lasting abbreviations the world has ever known. (And it has plenty of parodies too. As the modern Romans themselves like to say, 'sono pazzi questi romani'—'These Romans are bonkers.')

Which Roman figures would you most like to invite to your dinner table?

Cicero would be my first choice. Despite the great novels by Robert Harris, he has a modern rep as a fearful old bore; but the Romans thought he was the wittiest man ever. (Cicero's problem, they said, was that he just couldn't stop cracking gags.) To sit next to him, I'd hope for the empress Livia—I don't believe the allegations of her poisoning habits. And a massage artist from some grand set of Roman baths, who would surely have the best stories to tell of all.

What would surprise people to learn comes from ancient Rome?

They were the first people in the West to sort out lavatory technology, though we would find strange their enthusiasm for “multi-seater” bathrooms, with everyone going together.

How about something that might surprise people about the way ancient Romans themselves lived?

Despite the popular image, they didn’t usually wear togas (those were more the ancient equivalent of a tux). In any Roman town you'd find people in tunics, even trousers, and brightly colored ones at that. But perhaps my favorite “little known fact” about Roman life is that when they wanted to talk about the size of a house, they didn't do it by floor area or number of rooms, but by the number of tiles it had on its roof!

Is there a period during ancient Rome's roughly thousand-year existence that you'd most like to visit, and why?

Before I wrote SPQR, I would have said the period under the first emperor Augustus, when Rome was being transformed from a ramshackle city of brick into a grand capital city. But as I worked on the book, I realized that the rather murky fourth century B.C. was the period when Rome stopped being just some ordinary little place in Italy, and really became “Rome” as we know it. So I'd like to go back there and take a peek at what was going on.

Do you have a favorite Roman slogan?

When the historian Tacitus said “They create desolation and call it peace” to describe the Roman conquest of Britain, he gave us a phrase that described the effects of many conquests over the centuries, up to our own.

Why does Rome still matter?

The extraordinary tradition that underpins much of Western literature is one thing—there has not been a day since 19 B.C. when someone hasn’t been reading Virgil's Aeneid. But so is the inheritance of our politics beyond terminology (Senate, capitol). The arguments that followed Cicero's execution of the Catiline without trial in 63 B.C. still inform our own debates about civil liberties and homeland security.