What the Medieval Olympics Looked Like

The Middle Ages didn’t kill the Games, as international sporting competitions thrived with chariot races and jousts

:focal(555x370:556x371)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/4a/e64ae688-57a4-4d19-92a1-a1b909fdea9f/jousting.jpg)

Postponed from last summer because of the global pandemic, the Olympics, beset by controversy for months now, will march on (for now) and open in Tokyo on July 23 (perhaps, however, without fans in attendance). The Games feel woven into the fabric of modern history, offering signposts that fix memory in much bigger stories—for example, of Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics before World War II, the protest by John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and the civil rights movement, or even the 1980 Miracle on Ice and the Cold War. The games at once live in our minds while evoking ancient Greece and conjuring an unbroken connection from now until then.

But the real history of the Olympic Games is a modern invention; its ancient roots heavily mythologized. In this version of the story, the supposed “Dark Ages” disappeared the Games like they supposedly did with so much else. The real history of the Games, and more broadly sports, is much more complicated.

The ancient Olympics likely began sometime in the eighth century B.C.E. but gained prominence in the following century, with participants coming to the ancient Greek religious sanctuary of Olympia on the Peloponnese peninsula from across the Hellenic world. These events eventually became part of a “quadressnial circuit of athletic festivals [including] the Pythia, Nemean and Isthmian games,” in the words of David Goldblatt. Soon, perhaps because of Olympia’s association with the veneration of Zeus, the Olympic Games became the preeminent event in that circuit (a circuit that in fact expanded as other cities created their own athletic competitions) and attracted massive crowds.

The games continued even after the Romans conquered Peloponnese, with the Romans themselves becoming enthusiastic sponsors and participants. They continued the cult of Zeus (now called “Jupiter”) and built heavily in the area, replacing a pseudo-tent city that housed the athletes with permanent structures, constructing more private villas for wealthy spectators, and improving the infrastructure of the stadiums and surrounding community. In addition, they expanded the number of events and participants, opening it up to non-Greeks and extending the length of the games by another day (from five days to six).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/6c/be6c6130-d950-4405-bea2-15292e29df0e/2880px-circus_mosaic1.jpeg)

For a long time, historians blamed the ending of ancient athletic competitions on the rise of Christianity, specifically the Roman emperors who viewed these sports as polytheistic holdovers. But then, as now, the real story can be found by following the money.

New research has shown that regional Olympics, with semi-professional athletes travelling to compete across the Mediterranean, continued until just after the fifth century C.E. The decline was rather one of economics and politics, as financial sponsorship fell heavily away from the state and onto the backs of private donors. Then, as cultural tastes shifted (in part, truthfully, due to Christianization) and local budgets periodically became strained, all events but those in the biggest cities were cancelled, never to return. Even then, some games lingered on until the early sixth century.

The popular perception is often that, in the words of one author, “the Middle Ages are where sports went to die.” But although events branded as “Olympics” came to an end, sports, even formal regional competitions, lived on.

In the Byzantine Empire, events like chariot racing remained a touchstone for civic life in Constantinople (and elsewhere) at least until the 11th century. This was an immensely popular sport in the empire, with formalized “factions” (or teams) competing against one another regularly. Fans dedicated to their faction filled stadiums, patronized fast food stalls, and cheered on their faction’s charioteers, who were often enslaved peoples from across the Mediterranean. Although many died during the course of their races, some (such as one named Calpurnianus who won over 1,100 races in the first century C.E.) could become fabulously famous and wealthy.

Then, as now, sports was also politics and chariot racing could play a central role in the fate of the empire. For example, in 532 C.E., a riot broke out at the Hippodrome in Constantinople when the two major factions of chariot-racing fans—the Blues and the Greens—united and attacked imperial agents. Emperor Justinian considered fleeing the capital but his wife, Theodora, herself a former actor and whose family had been part of the Greens, convinced him to stay with the (probably apocryphal) words, “Reflect for a moment whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you would not gladly exchange such safety for death. As for me, I agree with the adage that the royal purple is the noblest shroud.” Justinian stayed and ordered the army to quell the riot. Some 30,000 people were said to have been killed in the ensuing bloodshed.

In the West, chariot racing died out rather quickly, but beginning in the second half of the 11th century, knightly tournaments were the spectacle of medieval Europe. At their height, beginning in the 12th century and continuing through at least the 16th, participants would, like their ancient Olympic forebears, travel a circuit of competitions across Europe, pitting their skills against other professionals. (The depiction in the 2001 Heath Ledger film A Knight’s Tale was not far from reality.) In these competitions, armored, mounted men would try to unseat their opponents using lance and shield, or battle on foot with blunted (but still dangerous) weapons to determine who was the best warrior, all for an enthusiastic crowd.

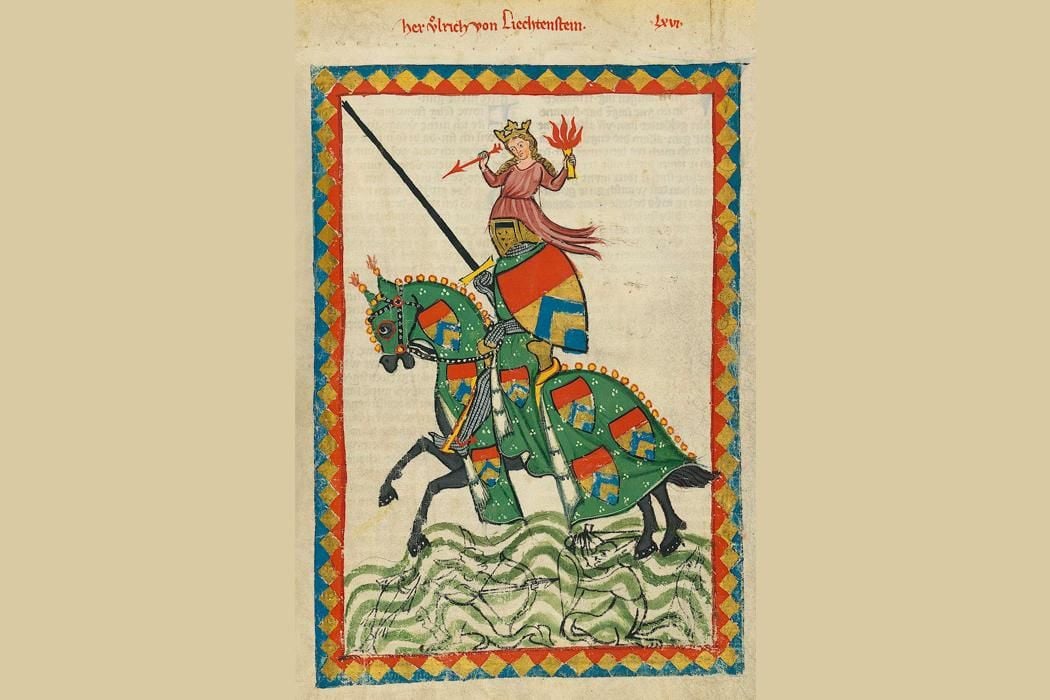

And indeed, these were performances. Lionized in contemporary fiction, and discussed repeatedly in historical chronicles from the period, one scholar has suggested that these were often accompanied—much like the modern Olympics—with theatrical opening and closing ceremonies. An autobiographical set of poems from the 13th century, for example, had the knight Ulrich von Liechtenstein perform a chaste quest for a wealthy (married) noblewoman. Dressed as a woman, specifically the goddess Venus, Ulrich travels across Italy and the Holy Roman Empire defeating all challengers in jousts and hand-to-hand combat.

In another instance, Jean Froissart, a late 14th-century chronicler who enjoyed the patronage of the queen of England and traveled widely during the Hundred Years War, told of one specific joust held at St. Inglevere (near Calais, France). During a lull in the hostilities between the kings of England and France, three French knights proclaimed a tournament and word was spread far and wide. Excitement particularly built in England, where great numbers of nobles wanted to put these French knights in their place. The tournament lasted 30 days and the three French knights tilted with the dozens of challengers one at a time until each had had his chance. At the end, everyone was satisfied and the English and French praised each other’s skill and parted in a “friendly manner.”

We should note the way that Froissart is very specific with names and their individual achievements, and how Ulrich is clear about his own achievements. Much like the modern Olympics, the prowess of the individual was of paramount concern for those who watched and those who read about the tournaments. In addition, both of these examples show how they were not military exercises, but spectacles: competitions and entertainments. Froissart is clear that French and English nobles, who in the past faced each other on the battlefield, were in this context friendly competitors, and these kinds of tournaments as a whole were, perhaps against our expectations, primarily about “amicable physical competition between noblemen from a variety of European courts.”

Sports history is history, in that athletic competitions both shape and reflect the times in which they take place. As the nobility began to spend less time on the battlefield after around 1600, they still rode horses and competed in sports, but the tournament died out. And at the end of the 19th century, the Olympics re-appeared thanks to a heady combination of rising nationalism across Europe and a redefinition of “proper” masculinity by elite white men who emphasized physical education. In 1896, they were held in Athens, then Paris in 1900, and St. Louis in 1904, and now they come to Tokyo. Let the games begin, but remember that sports operate as signposts within a broader history, and always have.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt.png)