On May 17, 1954, a man named P.D. East spent part of his workday photographing a chicken egg that weighed a quarter of a pound. An egg of that heft qualified as news in Petal, Mississippi, and as the owner of the weekly Petal Paper, East covered the local news. “We have no bones to pick with anyone,” he had announced in his first issue, a few months before. “Therefore, there will be no crusades, except when it is to the public interest.” For the first time in his life, East, at age 32, was making decent money and a place for himself in his community.

Also on that May 17, the Supreme Court of the United States released its decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, outlawing racial segregation in public schools. Over the next several months, as East absorbed what the ruling would mean for Mississippi, he found himself agreeing with the court’s reasoning and its 9-0 opinion. The vast majority of his advertisers did not, so he kept his thoughts to himself. “I didn’t entertain any thought of coming out against the mores of the society in which I had been born and reared,” he recalled.

Then Mississippi, like most Southern states, began taking steps to preserve its segregated society. The legislature passed a law requiring citizens to interpret, in writing, parts of the state constitution in order to register to vote. Lawmakers established the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, which doubled as a tourism-promotion board and an intrastate spy agency. In communities around the state, townspeople organized White Citizens’ Councils to counter advocacy for civil rights.

“I closed my eyes and ears tighter,” East remembered later. “But inside my heart and mind something was wrong. My moods of depression were frequent; my outbursts of temper were frequent. I knew neither why nor what. One thing I did know: I had to get it out, whatever it was.”

So he sat in his office one day in the spring of 1955 and wrote that it was time for a new symbol for the Magnolia State. After all, “once you have seen a magnolia, you have seen all magnolias.” Therefore, “as a 100 percent red-blooded Mississippian, we feel the magnolia should give way to the crawfish—and soon, too.” The crawfish was fitting, he wrote, because it moves only “backward, toward the mud from which he came,” and “progress in our state is made that way.”

When the Petal Paper came out several days later, the response was muted: East received two phone calls, both from men who seemed to mistake his sarcasm as ridiculing Mississippi’s black population. They bought subscriptions. “Unfortunately,” the newspaperman recalled, “the lack of reaction gave me a false sense of security; it let me go blindly into a fool’s paradise.”

**********

Thus the tiny Petal Paper, circulation 2,300 at its peak, launched one of the most relentless and single-minded crusades in the history of the Southern press, during which East went from being an eager-to-please businessman to what he called an “ulcerated, pistol-packing editor” who took on the biggest issue of his day with unforgiving satire. His unique stand for racial equality put him in touch with Eleanor Roosevelt, William Faulkner, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Upton Sinclair, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and the TV entertainer Steve Allen and his actress wife, Jayne Meadows. It also got East spied on, spat upon and threatened with violence and worse.

Historians have described Jim Crow-era Mississippi in exceptionally harsh terms. Joseph B. Atkins, a journalism professor at the University of Mississippi, notes that in the 1950s and ’60s it was “as close to a fascist state as has ever existed in the United States.” James W. Silver, in his landmark 1964 book Mississippi: The Closed Society, described the state as a place where the tenets of white supremacy went virtually unchallenged in the press, in the pulpit and in politics. East matters because he raised a voice in protest when almost no one else would (and in a county named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general and founder of the Ku Klux Klan). The Petal Paper was “a beacon of hope in an otherwise dark area,” a fellow Mississippi editor, Easton King, wrote to him. He added: “If you can take the stand for moderation you have and survive, others will take hope and eventually may speak out in behalf of sanity.”

In time, other Southern journalists did so, and their work has long overshadowed East’s. That’s partly because his newspaper was so small, but also because his preferred method was satire. Though he was right to say “if you can make a body laugh at himself, you can make some progress,” such progress is difficult to measure. Unlike other editorialists, East didn’t target a specific law or regulation and thus received no credit for overturning one; rather, he took aim at racism itself. Now scholars are reassessing his pioneering but forgotten brand of social satire. One expert sees East as a sort of Jon Stewart precursor—acerbic and angry, combating hypocrisy with humor, yet idealistic and persistent in a time and place that vilified dissent in the press. East got into the fight for equality early on, and he stayed as long as he could.

Percy Dale East was a big man—6-foot-2 and 225 pounds—and he’d learned how to fight as a child. Born in 1921, he was raised in a series of sawmill camps in southern Mississippi. His father was a blacksmith, and his mother ran a series of boardinghouses. He learned the prejudices of the South both at home and at school. His mother once told him to stay away from a kindly Italian produce vendor because “he’s just different from us,” and while he was in elementary school in the village of Carnes, he watched a principal take a tire iron to a black man’s head for asking the educator to move his car. At the same time, East’s status as a child of the camps led him to understand prejudice from the other side. In Carnes, as he and other students walked nearly a mile from the camp to the school, a school bus would pass them by. “There was enough room for all of us to ride on the bus,” he recalled, “but we were not allowed to do so.”

After graduating from high school, he was rejected by the Navy, thrown out of a community college, and briefly employed in Greyhound’s baggage department. Around the time the Army drafted him, in 1942, his mother asked that he visit her. When he did, she told him the true story of his birth: He’d been adopted as an infant. His birth mother, a touring pianist, had been on her way to her family’s farm in northern Mississippi when she gave birth to a son she did not want. A local doctor helped James and Birdie East take the boy in.

The revelation “knocked the props from under me,” he recalled. Later, when he was stationed at Camp Butner, in North Carolina, he received a letter from Birdie East saying his birth mother had died in Texas. He began suffering inexplicable blackouts, and he was medically discharged. He moved to Hattiesburg, a Mississippi railroad town of 30,000 people, but his distress persisted until he visited his birth mother’s burial site. “As I stood in the cemetery beside the grave,” he said, “I felt the deepest compassion I’ve ever known....I felt a great desire to weep, but tears wouldn’t come. I think it was pity or compassion in the broadest sense of the word. In any event, I didn’t hate the woman, and I was glad to know that.”

Over the next decade he got married (to the first of four wives) and worked for a railroad company long enough to figure out that he wanted to do something else. In 1951, having taken some writing courses at Mississippi Southern College, he began editing two union papers in Hattiesburg, the Union Review and the Local Advocate. He liked the work, especially the $600 a month it paid, and decided to start a community newspaper. Hattiesburg already had a daily, the American, so East set up shop in Petal, on the other bank of the Leaf River, in 1953.

The Petal Paper made money almost immediately. Its owner moved into a better house, bought a second car and joined the Kiwanis Club. On the paper’s first anniversary, in November 1954, he printed a notice thanking readers and advertisers and saying he was “looking forward to another year of pleasant associations with each of you.” But Brown had already been the law of the land for six months, and East couldn’t hold his tongue any longer.

A few days after he printed his crawfish editorial, he received a note from Hodding Carter II, owner of the Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville and another rare advocate for equality. Carter clearly got the point. “I hope you leave a forwarding address,” he wrote.

But East had no intention of leaving.

**********

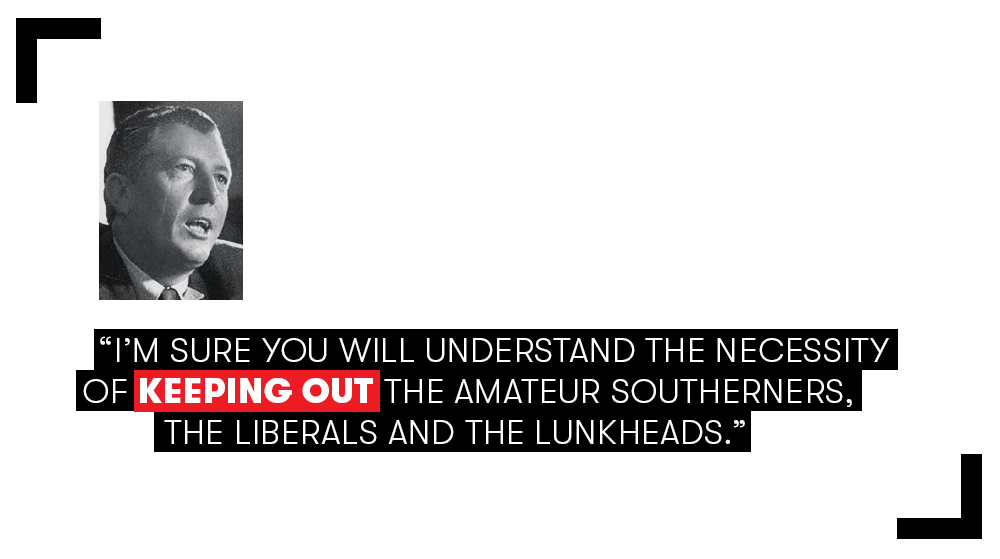

In 1955, Mississippians elected a new governor, James P. Coleman, who disputed those who characterized him as a moderate and proclaimed himself a “successful segregationist.” During the campaign, East invented a character named Jefferson D. Dixiecrat and printed in the Petal Paper a speech Dixiecrat gave as president of the Mississippi chapter of the Professional Southerners Club.

“I want to apologize to each of you at this time for asking that your Professional Southerners Club cards be inspected at the door before you were allowed to enter,” he wrote, “however, I’m sure you will understand the necessity of keeping out the amateur Southerners, the liberals and the lunkheads.” After noting the threat to “everything we hold sacred,” he continued his caricature, having Dixiecrat use an offensive word for African-American: “Our enemies say that our state needs more industry, but I say to you we need no industry where the n----- can make good wages, buy good clothes, good food, good homes. I say to you we need to return to the days when cotton was a dollar a pound and n----- labor was a dollar a day.”

After the parody appeared, Mark Ethridge, editor of the Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky, wrote East: “I wish Mississippi had more voices like yours and I hope you stay there.” Sentiment around Petal was different. “My relationship with some of the members of Kiwanis was, to put it mildly, strained,” East said. He quit the club. When a Hattiesburg businessman declined to buy an ad in the Petal Paper because East had criticized the man’s favored candidate for governor, the publisher went into high dudgeon in an editorial: “With the help of God, and to this we swear, as long as we can keep our head above water we will print what we please in this paper, so long as we believe it to be right, fair, or true. And if the time should come that to keep our head above water means to submit to pressure of any kind, then we will go under without hesitation, and at least with a clear conscience.”

“The editorial did little for business,” he wrote later, “but for my soul—it helped.”

Later in 1955, the University of Mississippi invited the Rev. Alvin Kershaw, a white Episcopal priest from Ohio, to speak during Religious Emphasis Week—and then disinvited him after he donated $32,000 he’d won on a TV quiz show to civil rights organizations. “Let it be said that Rev. Kershaw made a wrong decision,” East wrote in an editorial. “Had he decided to give some of his TV winnings to the Citizens’ Councils of Mississippi, then he would have been welcomed in our fair State.”

While East sounded resolute on the page, he struggled with depression, what he called “black days.” “In my desperation I found one place to go, a place I’d not been for a long time, and that was on my knees,” he recalled. “...While I still didn’t hear a word out of God, I began to understand the value of prayer.” This awakening, in turn, led East, in early 1956, to mock Christians who opposed integration: “Well, in view of the ruling of the United States Supreme Court, we have begun to wonder how it will affect that city called Heaven, if at all,” he wrote. “We have always sort of thought that Heaven was reserved for white folks, Mississippi Christians, especially. But now we have some doubt about the whole business.”

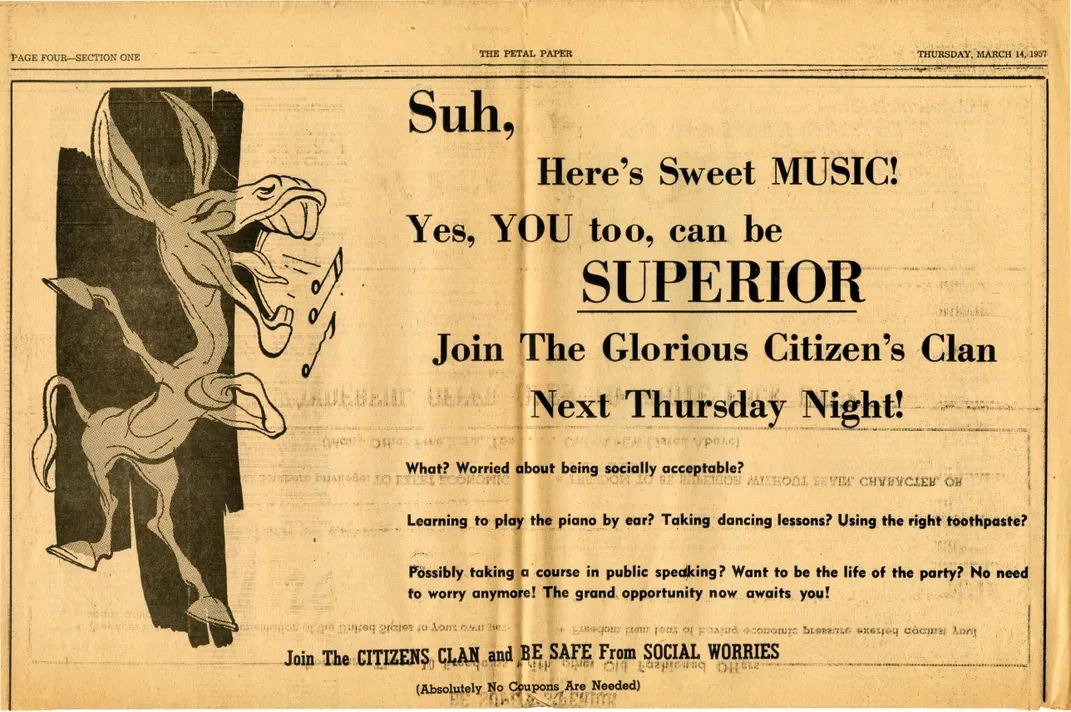

The following month, the White Citizens’ Council formed a Hattiesburg chapter. East published a fake full-page ad featuring a singing jackass. “Suh, here’s sweet MUSIC!” the animal sang. “Yes, YOU too, can be SUPERIOR. Join the Glorious Citizen’s Clan.” Below the fold, the ad noted that members were free to “interpret the Constitution of the United States to your own personal advantage,” as well as “to be superior with brain, character, or principle!” He later printed a list of all the good things the council had accomplished for Mississippi. The page was blank.

He started getting phone calls from readers, “one or two seeing fit to let me know they considered me a ‘n-----—loving, Jew-loving, Communist son-of-a-bitch.’” As he kept on, the epithets turned into threats, and became so numerous that East made the telephone line private. He later joked that the Petal Paper was the nation’s only newspaper with an unlisted number.

The stress, though, was getting to him. His hair was going prematurely gray and he was developing a stomach ulcer. “As the weeks passed my apprehension grew,” he recalled. “I had no idea what to expect next.” He began carrying a Luger.

**********

In the summer of 1956, East was invited to Oxford to speak with other Mississippians about starting a political party for moderates. William Faulkner, who hosted the group, asked East how a man with his background had come to hold his views on equality. “Bill,” East said, “I think for the simple reason that I believe in God.” The political party never came together, but when the novelist recruited him to edit a satirical newspaper aimed at college students, East produced the four-page Southern Reposure almost single-handedly. It was vintage East satire—it purported to be a member of the “Confederate Press Association” and railed against “the Scotch-Irish among us” as “a terrible menace to our way of life.” It vanished after a single issue.

Now the Petal Paper was in trouble. By the end of 1956, circulation was down to 1,000—and only nine subscribers were local. East went $4,000 in debt and considered folding the business, but Easton King wrote to remind him, “The Petal Paper is important as a symbol.”

That December, when the segregationist president of a private Baptist college in Mississippi retired, East published a fictitious job ad: “Must be a Baptist preacher, have Ph.D. union card. Must arrange for time for various speaking engagements for the Ku Klux Councils of Mississippi....Botanical knowledge not a necessity, but applicant must be able to determine difference between white magnolia and black orchid.”

To save money, East closed the paper’s office and worked out of his house. Respite of a sort came in 1957, after Albert Vorspan, director of the Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism, wrote a profile of East that appeared in the March issue of the magazine The Reporter. “My colleagues thought I was crazy for going to that dangerous state to spend time and try to help such a nobody,” Vorspan, who is now 94, told me. “I loved P.D. for his courage, his humor and the gutsy little Petal Paper.” The profile led to a spike in out-of-state subscriptions. Within two years, a group of non-Mississippians, including Steve Allen, Eleanor Roosevelt and the writer Maxwell Geismar, formed the Friends of P.D. East. They donated money to him for the rest of his life.

Such support did nothing for his standing in Mississippi. In 1959, an agent for the Sovereignty Commission wrote a memo recommending that “further efforts should be made to determine background information relative to Percy Dale East and just what he might be endeavouring to do at Petal. Any connection he might have with the NAACP should be developed. It has also been indicated that he might have an interest in the Communist Party.”

That year, while John Howard Griffin was traveling the South with his white skin dyed black to research his groundbreaking book Black Like Me, East took him in for several days. Griffin’s book describes his shock at the extent of East and his second wife’s isolation: “Except for two Jewish families, they are ostracized from society in Hattiesburg.”

In 1960, Simon & Schuster published East’s memoir, The Magnolia Jungle, in which he struggled to articulate how he came to believe so fiercely in equality. “Perhaps I’m the confused and frustrated soul that I am because of a man whose name I don’t remember, a man ‘who’s just not our kind of people,’ who sold fruit and vegetables at a sawmill camp....One thing I know: it not only could be, it is, the fact that I want a better place in which to live.”

To promote the book East appeared on the “Today” show, and not long after that, at a gas station in Mississippi, a stranger approached him and said, “Somebody ought to kill you, you son of a bitch.” As East eased into his Plymouth, the man added, “You’re a God damned traitor.” When East drove away, the man spit on his back window. A man passing him on the sidewalk called him a bastard. Another, spotting him in a grocery store, hollered, “Hello, Mr. NAACP.” With the election in 1959 of Gov. Ross Barnett, a staunch segregationist and the son of a Confederate veteran, Mississippi’s white supremacists had been emboldened.

The Magnolia Jungle: The Life, Times, and Education of a Southern Editor

First published in 1960, this book tells of author P. D. East’s trials and tribulations as a liberal editor during the times of the civil rights movement in the Deep South.

By 1962, East suspected a neighbor was jotting down the license-plate number of anyone who visited his house. He might have been paranoid, but his Sovereignty Commission file includes a 1963 letter suggesting he was under surveillance. The writer—whose name was redacted, but who apparently was a non-Southerner who had visited Mississippi to help register voters, and was writing to someone back home—recounted that he had asked East “what whites here could do, and he said he’s been trying to answer that question for 10 years.”

By the fall of that year East was divorcing his third wife, but their disunion seems to not have been rancorous: In mid-October, she called him from Texas and warned him to get out of Mississippi. Her lawyer, based in Hattiesburg, had told her that a segregationist group in Jackson was offering $25,000 to anyone who silenced East. He doubted it until the next day, when his former brother-in-law told him another group, one closer to Hattiesburg, was plotting to kill him.

“I don’t mind telling you,” East wrote to Geismar, “I’m scared.” Geismar told him to keep packing his gun: “I have lost patience to a degree with the idea of pacifism in situations like this, when you can be a sitting duck for racist hoods.”

The year 1963 brought a wave of spectacular violence directed at members of the civil rights movement. In April, Bill Moore, a white member of the Congress of Racial Equality, was shot twice in the head at close range while on a march in Alabama. In June, an assassin gunned down Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s Mississippi field secretary, in his driveway in Jackson. In September—just a few weeks after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C.—a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham killed four young girls and injured 22 other people.

Now, after eight years of trying to prick the conscience of his community, East was ready to move on. Griffin suggested he move to Texas with him, but East declined. He said he wanted to stay closer to home: “If I have roots, God help me, they’re here.”

**********

East moved to Fairhope, Alabama, and published the Petal Paper monthly out of his rented house, but it wasn’t the same. The paper was losing money—and some of its fire. His voice was most powerful when it was coming from close proximity to the White Citizens’ Council.

On one of his habitual visits to a Mobile bookstore, he met Mary Cameron Plummer, the owner’s daughter. Cammie, as she was called, was an undergraduate at Wellesley College, and had once been the novelist Harper Lee’s guest for a week in New York City. She was 19, East 42. He launched a prolonged charm offensive to overcome Cammie’s parents’ unease, and the couple were married in December 1965. They had friends. They gave parties. Students and faculty from the University of South Alabama’s history department would drop by to discuss current events. Strangers often showed up at his doorstep, looking to pay their respects. A houseguest of East’s during this time recalled his playing Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” on the phonograph and humming along as he made breakfast. “He said he didn’t like people,” Cammie would write in the final issue of the Petal Paper, “and yet I’ve never seen anyone as persistent or as thoughtful in enjoying friendships or in trying to help a friend.”

But East’s ideas weren’t always popular. The Easts bought a boat and christened it Chicken of the Sea, but they were denied admission to the Fairhope Yacht Club—members feared that he would invite African-American guests to dinner, Cammie recalled. A mechanic and a postmaster once told her some law-enforcement types had been around asking about what P.D. was up to. When the couple had to travel through Mississippi, P.D. insisted that Cammie drive, lest he be stopped on a trumped-up traffic charge.

By the late 1960s, his health was failing. He had headaches and trouble with his ulcer. A doctor diagnosed acromegaly, a gland disorder that causes bones in the head, hands and feet to grow unnaturally. P.D. East died on New Year’s Eve, 1971, in a Fairhope hospital, at the age of 50. A doctor said his liver failed. Cammie’s view is different. “In a sense,” she told me, “he died of Mississippi.”

**********

In the years after Brown was decided, most Southern newspaper editors either glossed over the upheaval that followed or sided with the segregationists. The exceptions were notable.

Hodding Carter II was one. In 1955, after state legislators passed a resolution denouncing him as a liar, he told them, in his newspaper, to “go to hell, collectively or singly, and wait there until I back down.” Ira Harkey, editor and publisher of the Chronicle Star in Pascagoula, pushed for the desegregation of the University of Mississippi and won a Pulitzer Prize for his editorials in 1963. The next year, Hazel Brannon Smith of the Lexington Advertiser became the first woman to win the Pulitzer for editorial writing, for her protests against racial injustice. The New York Times published obituaries of Carter, Harkey and Smith, celebrating their steadfastness in the face of hostility and financial ruin.

When Percy Dale East died, the Northern press took no notice, and the weekly Fairhope Times misidentified him as “Pete D. East.”

The memoir he’d left behind was well-reviewed but rarely purchased. A biography of East, Rebel With a Cause, by Gary Huey, was published in 1985 but has long been out of print. The Press and Race, a 2001 collection of essays about Mississippi journalists and the civil rights movement, included none of his writing.

But the editor of that collection, David R. Davies, has come to regret that decision. “Moderate and liberal editors constituted the first cracks in the solid wall segregating the races,” Davies told me, and East mattered because he was one of the first into the fray. Other researchers have reached similar conclusions. East was “the Jon Stewart of his day,” in the judgment of Davis Houck, the Fannie Lou Hamer professor of rhetorical studies at Florida State University. Clive Webb, a historian at the University of Sussex who came across East’s work while researching Jewish figures in the civil rights movement, said he is “unjustly neglected.”

Hodding Carter III, who succeeded his father at the Delta Democrat-Times before he served as an assistant secretary of state during the Carter administration, told me he admired East’s work even as he questioned his satirical means. “In small-town Mississippi, you either stayed in step or kept your mouth shut if you wanted to stay in business, stay in town and stay above ground,” he said. “P.D. did neither, which made him well nigh unique.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/f5/62f5be91-ef72-4648-ad1b-e2977d3e4c9a/sep2018_c04_pdeast.jpg)