Why We’d Be Better Off if Napoleon Never Lost at Waterloo

On the bicentennial of the most famous battle in world history, a distinguished historian looks at what could have been

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/f7/37f76041-e0f6-4087-8388-ec211c26a9fb/jun2015_j04_waterloo.jpg)

"Come general, the affair is over, we have lost the day," Napoleon told one of his officers. "Let us be off." The day was June 18, 1815. By about 8 p.m., the emperor of France knew he had been decisively defeated at a village called Waterloo, and he was now keen to escape from his enemies, some of whom—such as the Prussians—had sworn to execute him.

Less than an hour earlier, Napoleon had sent eight battalions of his elite Imperial Guard into the attack up the main Charleroi-to-Brussels road in a desperate attempt to break the line of the Anglo-Allied army commanded by the Duke of Wellington. But Wellington had repulsed the assault with a massive concentration of firepower. "Bullets and grapeshot left the road strewn with dead and wounded," recalled a French eyewitness. The guard stopped, staggered and fell back. A shocked—indeed, astounded—cry went up from the rest of the French Army, one unheard on any European battlefield in the unit's 16-year history: "La Garde recule!" ("The Guard recoils!")

The next cry spelled disaster for any hopes Napoleon might have had for an orderly retreat: "Sauve qui peut!" ("Save yourselves!"). Across the three-mile battlefront men threw down their muskets and fled, terrified of the Prussian lancers who were being ordered to pursue them with their eight-foot spears. In mid-June, darkness would not descend on that part of Europe for hours. Soon general panic set in.

“The whole army was in the most appalling disorder,” recalled Gen. Jean-Martin Petit. “Infantry, cavalry, artillery—everybody was fleeing in all directions.” Napoleon had ordered two squares of the Imperial Guard to form up on both sides of the highway to cover such a rout, and he took refuge within one of them as his army collapsed. “The enemy was close at our heels,” wrote Petit, who commanded the squares, “and, fearing that he might penetrate the squares, we were obliged to fire at the men who were being pursued.”

Taking a few trusted aides with him, as well as a squadron of light cavalry for personal protection, Napoleon left the square on horseback for the farmhouse at Le Caillou where he had breakfasted that morning, full of hopes for victory. There he transferred into his carriage. In the crush of fugitives on the road outside the town of Genappe he had to abandon it for a horse once again, although there were so many people that he could hardly go at much more than a walking pace.

“Of personal fear there was not the slightest trace,” one of Napoleon’s entourage, the Comte de Flahaut, wrote later. But the emperor was “so overcome by fatigue and the exertion of the preceding days that several times he was unable to resist the sleepiness which overcame him, and if I had not been there to uphold him, he would have fallen from his horse.” By 5 a.m. on June 19 they stopped by a fire some soldiers had made in a meadow. As Napoleon warmed himself he said to one of his generals, “Eh bien, monsieur, we have done a fine thing.” It’s a sign of his extraordinary sangfroid that even then, he was able to joke, however glumly.

Timeline of Napoleon's Life

1769 - Birth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/8c/ae8cbed7-8134-43c0-b9af-54dcc5afd3f8/waterloobirth.jpg)

Letizia di Bunoaparte barely makes it home from church in time to give birth to Napoleon, her fourth child, on August 15 (right, his birth certificate).

1785 - Commissioning as Second Lieutenant

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/b5/8cb5b245-ba3d-4665-ad14-80fb44218e66/jun2015_j12_waterloo.jpg)

Napoleon completes the two-year artillery program at the École Militaire in one year; is commissioned a second lieutenant at age 16.

1789 - Storming of the Bastille

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/d1/a3d12a81-baa1-4f6c-8ab2-ec817dd20dd6/jun2015_j11_waterloo.jpg)

"Calm will return" in a month, he writes, but the storming of the Bastille unleashes a decade of violence.

1791 - King Louis XVI Captured

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/4b/d34b8e14-1b0c-4c59-8927-27df592b625e/42-63210318.jpg)

King Louis XVI is captured trying to escape France. "This country is full of zeal and fire," writes Napoleon, now a first lieutenant and a proponent of the French Revolution.

1793 - French Government Guillotines Louis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/6b/166b6579-9044-40a1-adb2-f5480c7e341f/waterlooguillotine.jpg)

The French government guillotines Louis; Napoleon laments, "Had the French been more moderate and not put Louis to death, all Europe would have been revolutionized."

1793 - Liberation of Toulon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/56/fa56f746-7d66-4524-b7ee-064349a74245/42-17214686.jpg)

Even with his horse shot out from under him, Napoleon liberates the French port of Toulon from monarchist forces; is promoted to brigadier general at age 24.

1794 - Imprisonment on Suspicion of Treason

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/6b/1c6b2b6a-d53c-41cc-b292-821e17d7c5c1/jun2015_j05_waterloo.jpg)

As some of his patrons are executed during France's Reign of Terror, Napoleon is imprisoned on suspicion of treason but released 11 days later for lack of evidence. He remains faithful to the ideals of the Revolution.

1795 - Insurrection in Paris

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/e5/50e5cc8e-355a-480e-b5dc-3205407a3f7a/42-57712541.jpg)

He uses artillery to quell an insurrection in Paris, saying, "The rabble must be moved by terror."

1796 - Marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/7c/fe7cf609-998f-44b2-bbd5-06a35ea803b4/jun2015_j01_waterloo.jpg)

He marries Joséphine de Beauharnais, a widow with two children, and leaves two days later to conquer Italy; she cuckolds him within weeks.

1799 - Becoming First Consul

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/7a/eb7a1208-c04b-4e08-aa86-a39015bf92e1/jun2015_j10_waterloo.jpg)

After a coup, Napoleon becomes first consul; in 1804 he is declared emperor, to be succeeded by an heir.

1809 - Marriage to Austrian Archduchess Marie Louise

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/e8/c7e821a0-ad48-45fe-b8a2-14d464734f59/jun2015_j14_waterloo.jpg)

"You have children, I have none," he tells Joséphine as they divorce; he soon marries the Austrian archduchess Marie Louise, who bears an heir.

1814 - Exile to Elba

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/20/bf2040b7-3b8c-4b50-9edd-d260c9299009/42-26406881.jpg)

Enemy forces take Paris and restore the monarchy as Napoleon retreats from Moscow; he is exiled to Elba, which he calls an "operetta kingdom."

1815 - Escape to Paris

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/d1/53d113be-431e-405b-897c-9cf4f72c3813/sf39042.jpg)

Napoleon escapes to Paris; King Louis XVIII flees; Europe's monarchies call Napoleon "a disturber of the world" and unite to crush him.

1821 - Death

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/c9/3cc946f6-b225-4104-b263-619cb5cd47f8/jun2015_j03_waterloo.jpg)

He dies of cancer at age 51 on St. Helena; while in exile there, he had said, "If I had gone to America, we might have founded a State there."

There was no denying that the Battle of Waterloo had been catastrophic. Except for the Battle of Borodino, which Napoleon had fought in Russia in his disastrous 1812 campaign, this was the costliest single day of the 23 years of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Between 25,000 and 31,000 Frenchmen were killed or wounded, and vast numbers more were captured. Of Napoleon’s 64 most senior generals, no fewer than 26 were casualties. The losses for the Allies were severe, too—Wellington lost 17,200 men, the Prussian commander Marshal Gebhard von Blücher a further 7,000. Within a month, the disaster cost Napoleon his throne.

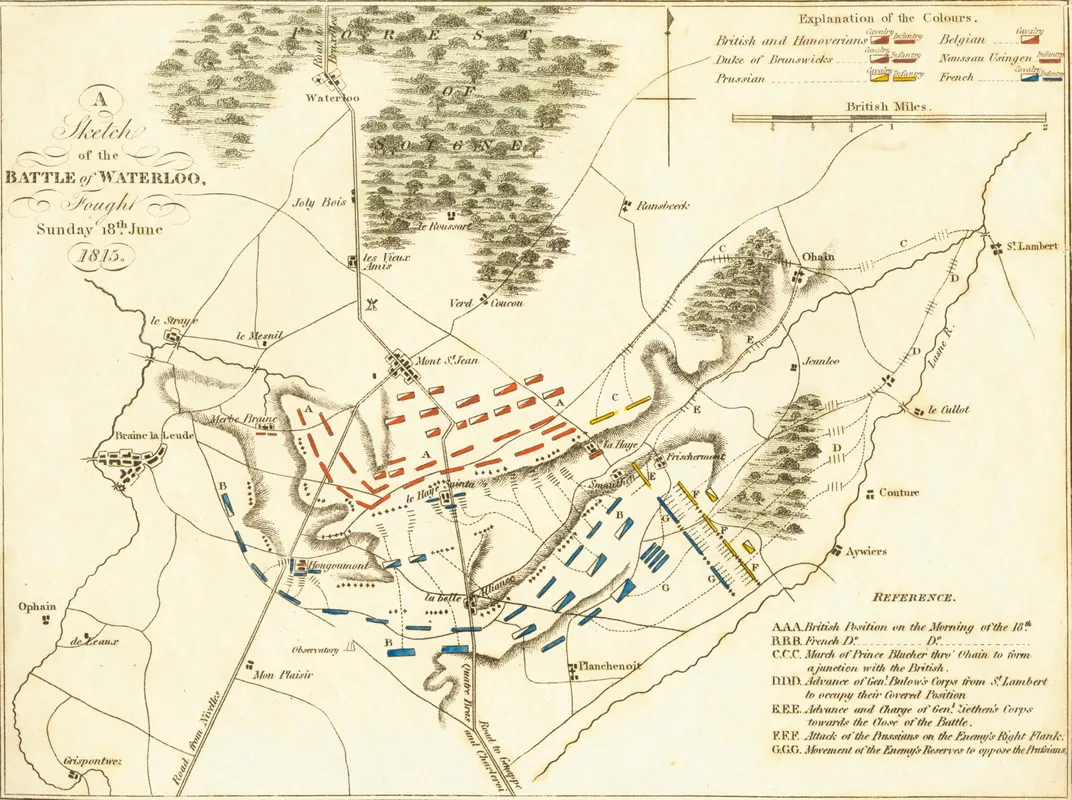

Walking the battlefield today, it’s all too easy to understand why he lost. From the 140-foot-high Lion’s Mound, which was built in the 1820s on top of Wellington’s front line, one can see what Napoleon could not: the woods to the east from which 50,000 Prussians started to emerge at 1 p.m. to stave in the French right flank, plus the two stone farmhouses of La Haie Sainte and Hougoumont, which disrupted and funneled the French attack for most of the day.

A vast amount of literature has explored why Napoleon fought such an unimaginative, error-prone battle at Waterloo. Hundreds of thousands of historians have pored over the questions of why he attacked when, where and how he attacked. Yet 200 years after the fact, a different question must be asked: Why was the Battle of Waterloo even fought? Was it really necessary to secure the peace and security of Europe?

**********

The future emperor of the French didn’t learn to speak their language until he was sent to boarding school at the age of 9. It was not his second language, but his third. Napoleone di Buonaparte was born on August 15, 1769, on the island of Corsica; for centuries a backwater province of Genoa, it had been sold to the French the previous year. He grew up speaking the corsicano dialect and Italian, and his name was Gaulified to Napoleon Bonaparte as he and his family painfully accommodated themselves to French rule. In fact, he was extremely anti-French until the age of 20, going through a period of adolescent angst in which he identified them as the enemy of his beloved freedom-loving Corsica.

Napoleon’s charming but indolent father, Carlo, died of cancer when Napoleon was only 15; the schoolboy had to mature early to help take care of his nearly bankrupt family. Yet at the military academy at Brienne he still had time to read and reread Goethe’s romantic novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, identifying with its honest but tragic hero. He later wrote his own melodramatic novel, Clisson and Eugénie, whose protagonist is a brilliant soldier crossed in love by a gorgeous but faithless beauty, clearly based on Eugénie Désirée Clary, a girlfriend who had recently refused his offer of marriage.

His antipathy for the French notwithstanding, the youthful Napoleon primarily identified with the Enlightenment and the dreams of Rousseau and Voltaire. That both were forced into exile by the French State only increased their appeal for him, as did their praise for the Corsican experiment that had been snuffed out the year before Napoleon was born. He also drew inspiration from the American Revolutionaries, who finally triumphed when Napoleon was an impressionable 14. (After George Washington died, in 1799, the recently installed French leader ordered that his nation go into ten days of mourning, compared with a mere two days after his first wife, the empress Joséphine, died 15 years later.) The French Revolution broke out with the fall of the Bastille when Napoleon was nearly 20; he eagerly embraced the Enlightenment ideas it at least initially represented.

Napoleon’s years at Brienne and then at the École Militaire in Paris (near where the Eiffel Tower is today) taught him the essence of modern warcraft. He put that knowledge to invaluable use in defense of the Revolution at the Battle of Toulon in 1793, which won him promotion to a generalship at the age of 24. Overall, he would win no fewer than 48 of the 60 battles he fought, drawing five and losing only seven (three of which were comparatively minor), establishing him as one of the greatest military commanders of all time.

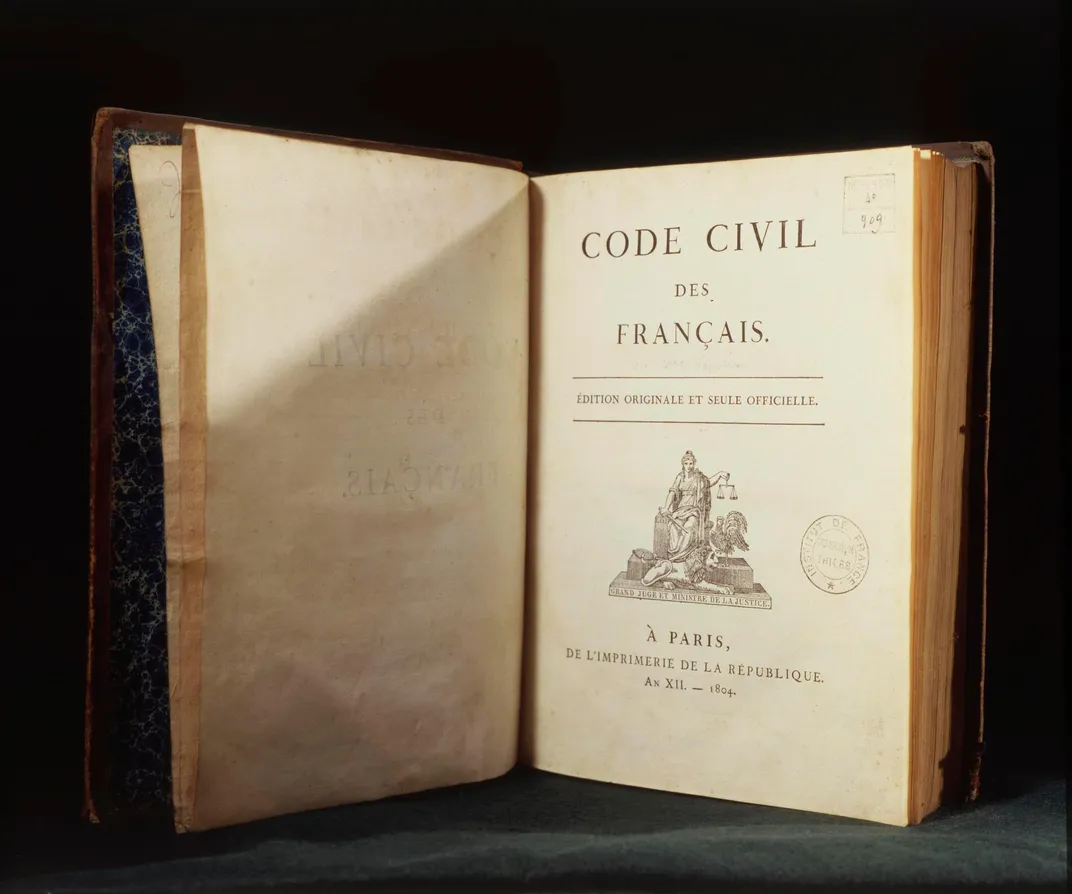

Yet he said he would be remembered not for his military victories, but for his domestic reforms, especially the Code Napoleon, that brilliant distillation of 42 competing and often contradictory legal codes into a single, easily comprehensible body of French law. In fact, Napoleon’s years as first consul, from 1799 to 1804, were extraordinarily peaceful and productive. He also created the educational system based on lycées and grandes écoles and the Sorbonne, which put France at the forefront of European educational achievement. He consolidated the administrative system based on departments and prefects. He initiated the Council of State, which still vets the laws of France, and the Court of Audit, which oversees its public accounts. He organized the Banque de France and the Légion d’Honneur, which thrive today. He also built or renovated much of the Parisian architecture that we still enjoy, both the useful—the quays along the Seine and four bridges over it, the sewers and reservoirs—and the beautiful, such as the Arc de Triomphe, the Rue de Rivoli and the Vendôme column.

Not least, Napoleon negotiated the 1803 sale to the nascent United States of the vast territory called the Louisiana Purchase. Americans are familiar with their side of the deal: It doubled their territory overnight at less than four cents an acre and instantly established the country “among the powers of first rank,” as Robert R. Livingston, President Thomas Jefferson’s chief negotiator, put it. But the French averted war with the United States over its inevitable expansion westward, and the 80 million francs they received allowed Napoleon to rebuild France, especially its army.

Napoleon crowned himself emperor on December 2, 1804, turning the French Republic into the French Empire, with a Bonaparte line of succession. He felt that this provision for continuity was prudent, given that the Bourbons launched a series of assassination attempts on him—30 in all. Yet this return to monarchy did not alleviate the ancien régime powers’ rancor over the French occupation of lands in Germany and Italy that had belonged to Austria for decades. In September 1805, Austria invaded Napoleon’s ally Bavaria, and Russia declared war on France as well. Napoleon swiftly won the ensuing War of the Third Coalition with his finest victory, at Austerlitz in 1805. The next year the Prussians also declared war on him, but they were soundly defeated at Jena; Napoleon’s peace treaty of Tilsit with Russia and Prussia followed. The Austrians declared war on France once more in 1809, but were dispatched at the Battle of Wagram and signed yet another peace treaty.

Napoleon started none of those wars, but he won all of them. After 1809 there was an uneasy peace with the three other Continental powers, but in 1812 he responded to France’s being cut out of Russian markets—in violation of the Tilsit terms—by invading Russia. That ended in the catastrophic retreat from Moscow, which cost him more than half a million casualties and left his Grande Armée too vitiated to deter Austria and Prussia from joining his enemies Russia and Britain in 1813.

**********

Napoleon’s relationship with Joséphine was not the Romeo-and-Juliet story often told. Shortly before their marriage, in March 1796, he was appointed commander in chief of the Army of Italy, where he won an astonishing series of more than a dozen victories against Austria, the papacy and local states, all the while writing her scores of erotic, emotionally needy love letters, even while under enemy fire. But within weeks his bride took a lover in Paris—the dandyish cavalry officer Lt. Hippolyte Charles, whom one of their contemporaries said “had the elegance of a wigmaker’s boy.” When Napoleon finally found out about the affair two years later, he was in the middle of the Egyptian desert, on his way to Cairo. He responded by bedding Pauline Fourès, the wife of one of his junior officers—the first of no fewer than 22 mistresses over the next 17 years.

When he returned to Paris a year later, Napoleon unexpectedly forgave Joséphine, and they created what amounted—his mistresses excepted—to a loving bourgeois family environment in which to raise Joséphine’s children by an earlier marriage at their palaces of Malmaison, Fontainebleau, the Tuileries and elsewhere. It was only in 1809, when it had become clear that Joséphine could not bear the son Napoleon needed to continue the Bonaparte dynasty, that he reluctantly divorced her and the next year married the Archduchess Marie Louise von Habsburg, the daughter of Emperor Francis I of Austria. She quickly bore a son, the king of Rome.

Napoleon later said he greatly regretted not marrying instead the sister of Czar Alexander I of Russia, believing—probably wrongly—that he would not have had to invade Russia in 1812. In any event, after he retreated from Moscow, the Continental powers and the British pursued his army into France. The emperor’s military skill was intact—he won four victories in five days in the Champagne region in February 1814—but he could not prevent his boyhood friend and longtime comrade in arms Marshal Auguste de Marmont from surrendering Paris to the Austrians, Prussians and Russians the next month. Napoleon abdicated rather than plunge France into a civil war. He was exiled to the tiny Mediterranean island of Elba in May.

That month Louis XVIII, the head of the Bourbon family, returned to France “in the baggage train of the Allies,” as the contemptuous but essentially accurate Bonapartist phrase put it. The Bourbons began ruling in France for the first time since Louis’ elder brother Louis XVI and his sister-in-law Marie Antoinette had been guillotined some 21 years earlier. As Napoleon adjusted to life ruling a much-reduced domain, he kept a close eye on what was happening in France.

It was said of the Bourbons that they “had learned nothing and forgotten nothing” when they returned to power. They had not learned from the French Revolution and Napoleonic Empire that the French people had changed profoundly and now took for granted meritocracy, low direct taxation, secular education and a certain degree of military glory. Nor had the Bourbons forgotten the expropriations and executions suffered by the royal family, the aristocracy and the Catholic Church during the Reign of Terror in the 1790s. As a result, they returned to France ill-prepared to effect a grand settlement that could reconcile the contesting demands of the army, clergy, aristocracy, peasantry, merchants, Bonapartists, liberals, ex-revolutionaries and conservatives.

Perhaps the task was impossible, but after nine months it became clear, even on distant Elba, that Louis XVIII had failed. Napoleon was emboldened to take the last and greatest gamble of his life.

**********

On February 26, 1815, he secretly boarded the largest ship in his tiny fleet and sailed to Golfe-Juan, on the south coast of France. The British and Bourbon frigates in the area didn’t learn of his escape until it was too late. Landing on March 1, Napoleon struck north with the 600 Imperial Guardsmen he had brought with him, over mountain passes and through tiny villages, sometimes on foot when the paths were too steep and narrow to ride down. The route he took from Cannes to Grenoble—today mapped out as the Route Napoleon for tourists, hikers and cyclists—is one of the loveliest (if more vertiginous) trails in the country.

Of course Louis XVIII sent armies to arrest him. But the commanders, Marshals Nicolas Soult and Michel Ney, and their men switched sides the moment they came into contact with the charisma of their former sovereign. On March 20, Napoleon reached the Tuileries Palace in Paris—on the site of the Louvre today—and was acclaimed by the populace. Col. Léon-Michel Routier, who was chatting with fellow officers nearby, recalled: “Suddenly very simple carriages without any escort showed up at the wicket-gate by the river and the emperor was announced....The carriages enter, we all rush around them and we see Napoleon get out. Then everyone’s in delirium; we jump on him in disorder, we surround him, we squeeze him, we almost suffocate him.” It was a “magical arrival, the result of a road of over two hundred leagues traveled in eighteen days on French soil without spilling one drop of blood.”

That night Napoleon sat down to eat the dinner that had been cooked for Louis XVIII, who had fled Paris only hours earlier. Not one shot had been fired in the Bourbons’ defense. “Never before in history,” said Parisian wags, “has an emperor won an empire simply by showing his hat.” (Napoleon’s bicorn hat had long been one of his many instantly recognizable symbols. This past November, one of his hats was auctioned to a South Korean businessman for $2.4 million.)

The Allies reacted with shocked disbelief. They were gathered at a congress in Vienna when news of his escape reached them on March 7, but initially the representatives of Austria, Russia, Britain and Prussia had no idea where he had gone. Once they established four days later that Napoleon had returned to France, they issued what has been called the Vienna Declaration: “By appearing again in France with projects of confusion and disorder, he has deprived himself of the protection of the law and has manifested before the world that there can be neither peace nor truce with him. The Powers consequently declare that Napoleon Bonaparte has placed himself beyond the pale of civil and social relations, and that as an enemy and disturber of the tranquility of the world, he has delivered himself up to public vengeance.”

This language, which seems extremely tough to modern ears, was a compromise from a draft offered by the French government, “which virtually called Napoleon a wild beast and invited any peasant lad or maniac to shoot him down at sight,” as the historian Enno E. Kraehe later put it. The Austrian chancellor, Prince Klemens von Metternich, softened the wording because Napoleon was still the son-in-law of the emperor of Austria, and the Duke of Wellington denounced the language as encouraging the assassination of monarchs. Nonetheless, the declaration clearly foreclosed any negotiation.

On April 4 Napoleon wrote to the Allies, “After presenting the spectacle of great campaigns to the world, from now on it will be more pleasant to know no other rivalry than that of the benefits of peace, of no other struggle than the holy conflict of the happiness of peoples.” By then the Allies had already formed the Seventh Coalition to destroy him and restore the Bourbons to the French throne, in defiance of the wishes the French people had expressed in a referendum. Thus they made the Waterloo campaign as inevitable as it was ultimately unnecessary.

**********

The foremost motive that the British, Austrians, Prussians, Russians and lesser powers publicly gave for declaring war was that Napoleon couldn’t be trusted to keep the peace. As one British member of Parliament put it, peace “must always be uncertain with such a man, and...whilst he reigns, would require a constant armament, and hostile preparations more intolerable than war itself.” That may have been true during his imperial period, but this time around Napoleon’s behavior suggested that the Allies could have taken him at his word.

He told his council that he had renounced any dream of reconstituting the empire and that “henceforth the happiness and the consolidation” of France “shall be the object of all my thoughts.” He refrained from taking measures against anyone who had betrayed him the previous year. “Of all that individuals have done, written or said since the taking of Paris,” he proclaimed, “I shall forever remain ignorant.” He immediately set about instituting a new liberal constitution incorporating trial by jury, freedom of speech and a bicameral legislature that curtailed some of his own powers; it was written by the former opposition politician Benjamin Constant, whom he had once sent into internal exile.

Napoleon well knew that after 23 years of almost constant war, the French people wanted no more of it. His greatest hope was for a peaceful period like his days as first consul, in which he could re-establish the legitimacy of his dynasty, return the nation’s battered economy to strength and restore the civil order the Bourbons had disturbed.

And so he resumed building various public works in Paris, including the elephant fountain at the Bastille, a new marketplace at St. Germain, the foreign ministry at the Quai d’Orsay, and the Louvre. He sent the actor François-Joseph Talma to teach at the Conservatory, which the Bourbons had closed, and also returned to their government jobs Vivant Denon, the director of the Louvre; the painter Jacques-Louis David; the architect Pierre Fontaine; and the doctor Jean-Nicolas Corvisart. On March 31, he visited the orphaned daughters of members of the Légion d’Honneur, whose school at Saint-Denis had had its funding cut by the Bourbons. That same day he restored the University of France to its former footing, appointing the Comte de Lacépède as chancellor. At a concert at the Tuileries he kindled a romance with the celebrated 36-year-old actress and beauty Anne Hippolyte Boutet Salvetat (whose stage name was Mademoiselle Mars).

All that Napoleon achieved in just 12 weeks after he returned to Paris—even as he prepared for the war the Allies had declared on him.

Like the Bourbons, they were in no mood to forgive or forget. In addition to their declared distrust, they had less-public motives for moving against him. The autocratic rulers of Russia, Prussia and Austria wanted to crush the revolutionary ideas for which Napoleon stood, including meritocracy, equality before the law, anti-feudalism and religious toleration. Essentially, they wanted to turn the clock back to a time when Europe was safe for aristocracy. At this they succeeded—until the outbreak of the Great War a century later.

The British had long enjoyed most of the key Enlightenment values, having beheaded King Charles I 140 years before the French guillotined Louis XVI, but they had other reasons for wanting to destroy Napoleon. Anything that distracted the British public’s attention from Andrew Jackson’s victory at New Orleans in January 1815 was very welcome, not least because the British commander there, Gen. Edward Pakenham, was the Duke of Wellington’s brother-in-law. More gravely, Britain and France had fought each other for no fewer than 56 years in the preceding 125, and Napoleon himself had posed a threat of invasion before Lord Nelson destroyed the French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar in 1805. With the French threat removed, the British were able to sign a peace treaty securing strategically important points around the globe, such as Cape Town, Jamaica and Sri Lanka, from which they could project their maritime power into a new empire to replace the one they’d lost in America. They, too, succeeded, building the largest empire in world history, which by the dawn of the 20th century covered nearly a quarter of the world’s land surface. The British could have achieved those goals even if they’d left Napoleon alone; they had total control of the oceans.

Once it became clear that the Allies were amassing huge armies to invade France and depose him again, Napoleon acted swiftly, leaving Paris on June 12 and striking north to defeat the Anglo-Allied army under Wellington and the Prussian Army under von Blücher before the Austrian and Russian armies, totaling half a million men, could arrive.

**********

Wellington later described the Battle of Waterloo as “the nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life.” Initially, the French outnumbered their opponents, especially in artillery. They were a homogeneous national force, and their morale was high, since they believed their commander was the greatest soldier since Julius Caesar. The first stages of the Waterloo campaign also saw Napoleon returning to the best of his strategic abilities. He wanted to fight in modern-day Belgium (then officially known as the Austrian Netherlands, though they no longer belonged to Austria) because the British and Prussian troops were far apart, and because capturing Brussels would be a great boost to French morale and might force the British Army off the Continent altogether. By achieving a brilliant feint toward the west, he managed to steal a day’s march on Wellington. “Napoleon has humbugged me, by God,” the Briton exclaimed.

Napoleon wanted to strike at the hinge between the Prussian and British armies, as he had done on other battlefields for nearly 20 years, and at first it seemed as if he’d succeeded. At the Battle of Ligny on June 16, he pinned the Prussians in place with a frontal attack and ordered a corps of 20,000 men under Gen. Jean-Baptiste d’Erlon to fall on the enemy’s exposed right flank. Had d’Erlon arrived as planned, it would have turned a respectable victory for Napoleon into a devastating rout of the Prussians. Instead, just as he was about to engage, d’Erlon received urgent orders from Marshal Ney to support Ney miles to the west, and so d’Erlon marched.

“Incomprehensible day,” Napoleon later said of that fateful June 18, admitting that he “did not thoroughly understand the battle,” the loss of which he blamed on “a combination of extraordinary Fates.” In fact, it was not incomprehensible at all: Napoleon split his army disastrously the day before the battle, put his senior marshals in the wrong roles, failed to attack early enough in the morning, didn’t discern that the Prussians were going to arrive in the afternoon, launched his major infantry attack in the wrong formation and his major cavalry attack at the wrong time (and unsupported by infantry and horse artillery), and unleashed his Imperial Guard too late. As he told one of his captors the following year: “In war, the game is always with him who commits the fewest faults.” At Waterloo, that was undoubtedly Wellington.

If Napoleon had remained emperor of France for the six years remaining in his natural life, European civilization would have benefited inestimably. The reactionary Holy Alliance of Russia, Prussia and Austria would not have been able to crush liberal constitutionalist movements in Spain, Greece, Eastern Europe and elsewhere; pressure to join France in abolishing slavery in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean would have grown; the benefits of meritocracy over feudalism would have had time to become more widely appreciated; Jews would not have been forced back into their ghettos in the Papal States and made to wear the yellow star again; encouragement of the arts and sciences would have been better understood and copied; and the plans to rebuild Paris would have been implemented, making it the most gorgeous city in the world.

Napoleon deserved to lose Waterloo, and Wellington to win it, but the essential point in this bicentenary year is that the epic battle did not need to be fought—and the world would have been better off if it hadn’t been.

Related Reads

Napoleon: A Life