Inside a Trailblazing Surgeon’s Quest to Reconstruct WWI Soldiers’ Disfigured Faces

A new book profiles Harold Gillies, whose efforts to restore wounded warriors’ visages laid the groundwork for modern plastic surgery

:focal(2128x1419:2129x1420)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/b7/bab70288-4423-44e5-be95-91fcaf7b692a/default5.jpeg)

Brilliant shards of crimson and gold pierced the eastern sky as dawn broke over Cambrai on November 20, 1917. The French city was a vital supply point for the German army positioned 25 miles from the Belgian border. On the dewy grass of a nearby hillside, Private Percy Clare of the Seventh Battalion, East Surrey Regiment, was lying on his belly next to his commanding officer, awaiting the signal to advance. In the distance, he could hear the faint staccato of the machine guns, and the whistle of the shells as they sailed through the air.

Shortly after the shelling began, his commanding officer gave the signal. Clare fixed his bayonet to his rifle and began marching down the exposed hillside with the other men in his platoon. Along the way, he passed a stream of wounded men, their faces blanched with terror. Suddenly, a shell burst overhead, temporarily obscuring the scene in a cloud of smoke. Once it cleared, Clare saw that the platoon ahead of his had been destroyed. One corpse in particular drew his attention. It was a dead soldier who was entirely naked, “every stitch of clothing blown from the body ... a curious effect of [a] high explosive burst,” Clare recalled in his diary.

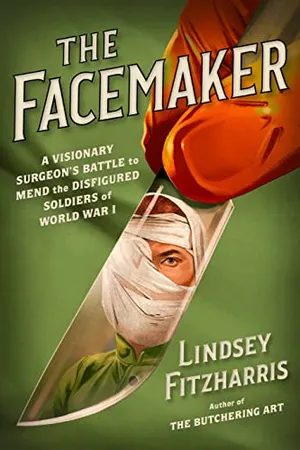

The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

Lindsey Fitzharris, the award-winning author of The Butchering Art, presents the compelling, true story of a visionary surgeon who rebuilt the faces of the First World War’s injured heroes, and in the process ushered in the modern era of plastic surgery.

Clare inched forward and negotiated tangles of barbed wire, keeping low to avoid the bullets flying overhead. Then, 700 yards from the enemy’s trench, he felt a sharp blow to the side of his face. A single bullet had torn through both his cheeks. Blood cascaded from his mouth and nostrils, soaking the front of his uniform. Clare opened his mouth to scream, but no sound escaped. His face was too badly maimed to even arrange itself into a grimace of pain. Clare was now one of countless men whose shattered faces had come to symbolize the worst of a new, mechanized form of war.

After the bullet ripped through his cheek, Clare’s first thought was that the wound would prove fatal. He wobbled on his feet for a moment before sinking to his knees, incredulous at the idea that he might die. “I had been through so many perilous times that I had unconsciously come to look upon myself as immune,” he later recalled in his diary.

As he drifted in and out of consciousness, he prayed that medical help would arrive soon. It did. In spite of daunting obstacles to rescue, he was soon lifted onto a stretcher. He later referred to the wound in his diary as a “Blighty One”—that is, an injury demanding specialized treatment that would require his return to Britain, known colloquially as “Old Blighty.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/f1/24f1bcda-be39-44eb-af9a-c0382732f161/screen_shot_2022-06-30_at_34615_pm.png)

Any relief Clare might have felt at that moment, however, was short-lived. The next time he saw his face in a mirror, he received a shock. With a heavy heart, he concluded, “I was an unlovely object.” Though he didn’t know it then, a forward-thinking surgeon named Harold Gillies was waiting in the wings, ready to offer innovative treatments for these novel injuries, giving Clare and thousands like him a second chance. He just had to survive long enough to reach the medical help that he so desperately needed.

From the moment the first machine gun rang out over the Western Front, one thing was clear: Europe’s military technology had wildly surpassed its medical capabilities. Bullets tore through the air at terrifying speeds. Shells and mortar bombs exploded with a force that flung men around the battlefield like rag dolls. Ammunition containing magnesium fuses ignited when lodged in flesh. And a new threat, in the form of hot chunks of shrapnel, often covered in bacteria-laden mud, wrought terrible injuries on its victims. Bodies were battered, gouged and hacked, but wounds to the face could be especially traumatic. Noses were blown off, jaws were shattered, tongues were torn out and eyeballs were dislodged. In some cases, entire faces were obliterated. In the words of one battlefield nurse, “[T]he science of healing stood baffled before the science of destroying.”

The nature of trench warfare led to high rates of facial injuries. Many combatants were shot in the face simply because they had no idea what to expect: “They seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of machine-gun bullets,” wrote one surgeon. Others, like Clare, sustained their injuries as they advanced across the battlefield. Men were maimed, burned and gassed. Some were kicked in the face by horses. Before the war was over, 280,000 men from France, Germany and Britain alone had sustained some form of facial trauma. In addition to causing death and dismemberment, the war was also an efficient machine for producing millions of walking wounded. Between eight and ten million soldiers died during the war, and over twice as many were wounded, often seriously. Many survived only to be sent back into battle. Others were sent home with lasting disabilities. Those who sustained facial injuries—like Clare—presented some of the greatest challenges to frontline medicine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/50/175097fc-7e61-489a-b3c2-5a3f3523799e/gettyimages-84388882.jpg)

Fortunately for many of these men, the visionary surgeon Gillies had recently established the Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, England—one of the first facilities in the world dedicated solely to facial reconstruction. Over the course of the war, Gillies would adapt and improve existing, rudimentary techniques of plastic surgery and develop entirely new ones, all in the cause of mending faces, and spirits, broken by the hell of the trenches.

Unlike amputees, men with facial features disfigured by war were not necessarily celebrated as heroes. Whereas a missing leg might elicit sympathy and respect, a damaged face often caused feelings of revulsion and disgust. In newspapers of the time, injuries to the face and jaw were portrayed as the worst of the worst, reflecting long-held prejudices against those with facial differences. The Manchester Evening Chronicle wrote that the disfigured soldier “knows that he can turn on to grieving relatives or to wondering, inquisitive strangers only a more or less repulsive mask where there was once a handsome or welcome face.” Indeed, Joanna Bourke, a historian at Birbeck, University of London, has shown that “very severe facial disfigurement” was among the few injuries that the British War Office believed warranted a full pension, alongside such afflictions as loss of multiple limbs, total paralysis and “lunacy”—what the medical community would later term shell shock, the mental disorder suffered by war-traumatized soldiers.

It’s unsurprising that disfigured soldiers were viewed differently from their comrades who sustained other types of injuries. For centuries, a marked face was interpreted as an outward sign of moral or intellectual degeneracy. People often associated facial irregularities with the devastating effects of disease, such as leprosy or syphilis, or with corporal punishment, wickedness and sin. In fact, disfigurement carried with it such a stigma that French combatants who sustained these wounds during the Napoleonic Wars were sometimes simply killed by their comrades, who justified their actions by claiming that they were sparing these injured men from further misery. The misguided belief that disfigurement was a fate worse than death was still alive and well during the First World War.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/4b/014be438-db37-4fd7-9aee-1ce9e15a6729/service-pnp-cph-3c30000-3c37000-3c37100-3c37180v.jpeg)

Upon their return, disfigured soldiers often suffered self-imposed isolation from society. The abrupt transformation from “typical” to “disfigured” was not only a shock to the patient, but also to his friends and family. Fiancées broke off engagements. Children fled at the sight of their fathers. One man recalled the time a doctor refused to look at him because of the severity of his wounds: “I supposed [the doctor] thought it was only a matter of a few hours then I would pass out of existence.” These reactions by outsiders could be painful for veterans. Robert Tait McKenzie, an inspector of convalescent hospitals for Britain’s Royal Army Medical Corps during the war, wrote that disfigured soldiers often became “victims of despondency, of melancholia, leading, in some cases, even to suicide.”

These soldiers’ lives were often left as shattered as their faces. Robbed of their very identities, such men came to symbolize the worst of a new, mechanized form of war. In France, they were called les gueules cassées (the broken faces), while in Germany, they were commonly described as das Gesichts entstellten (twisted faces) or Menschen ohne Gesicht (men without faces). In Britain, they were known simply as the “Loneliest of Tommies”—the most tragic of all war victims—strangers even to themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/35/49/354933c5-f889-453e-b557-e6bce6548f6e/walter_yeo_skin_graft.jpeg)

Doctors and nurses at wartime hospitals experienced enormous challenges, but none was more daunting than the one posed by men with facial injuries. For these patients, survival alone wasn’t enough. Further medical interventions were necessary if these men had any hope of returning to some semblance of their former lives. Whereas a prosthetic limb did not necessarily have to resemble the arm or leg it was replacing, a face was a different matter. Any surgeon willing to take on the monumental task of reconstructing a soldier’s face not only had to address loss of function, such as the ability to eat, but also consider aesthetics in order to reflect what society deemed acceptable.

Complicating matters, plastic surgery was not yet a formal discipline, and virtually no British surgeon had any clinical experience in this field. Efforts in earlier periods to rebuild, repair or otherwise alter the appearance of a patient’s face were typically confined to small, specific areas, such as the nose or the ears. Still, the most basic operations remained rare, even as developments in anesthetics in the latter half of the 19th century made them less painful than in previous periods. “This was a strange new art,” Gillies later recalled, “and unlike the student today, who is weaned on small scar excisions and gradually graduated to a single harelip, we were suddenly asked to produce half a face.” With no textbooks to guide him and no teachers to consult, Gillies had to rely on his imagination to help him visualize solutions to the problems set before him.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/df/43df317e-530d-4bbf-bf8e-fdeea386c689/screen_shot_2022-06-30_at_33849_pm.png)

What was needed, Gillies thought, was a hub where a variety of practitioners could come together to address the staggering number of facial injuries being inflicted on the Western Front. To help him with this daunting challenge, Gillies assembled a unique group of practitioners at the Queen’s Hospital whose task would be to restore what had been torn apart, to recreate what had been destroyed. This multidisciplinary team would include surgeons, physicians, dentists, radiologists, artists, sculptors, mask-makers and photographers, all of whom would assist in the reconstruction process from beginning to end, and some of whom would help restore Clare’s face at Sidcup—and his hope for a life after war. Under Gillies’s leadership, the field of plastic surgery would evolve, and pioneering methods would become standardized as an obscure branch of medicine gained legitimacy and entered the modern era. It has flourished ever since, challenging the ways in which we understand ourselves and our identities through the reconstructive and aesthetic innovations of plastic surgeons the world over.

Excerpted from The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I by Lindsey Fitzharris. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Lindsey Fitzharris. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.