SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Have Antillean Manatees Crossed the Panama Canal into the Pacific?

Over half a century ago, a group of manatees from Panama’s Caribbean region of Bocas del Toro was flown into the Panama Canal to control the abundance of aquatic plants in its water reservoir and prevent the proliferation of disease-transmitting mosquitoes. Where are they now?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/13/7c1326ba-80a7-4497-891d-4d9929a8557a/vol_ii_no51_06_junio-12-1964-001-pamelita_ii.jpg)

In the mid-sixties, almost 50 years after the creation of the artificial Gatun Lake for the operations of the Panama Canal, the Health Bureau of the Panama Canal Company (PCC) flew manatees (Trichechus manatus manatus) in to populate the water reservoir. Aquatic plants, such as the water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes), had become abundant and health authorities feared their potential as breeding grounds for disease-transmitting mosquitoes. Manatees, as had been tested in Guyana, were a species that could help control the problem.

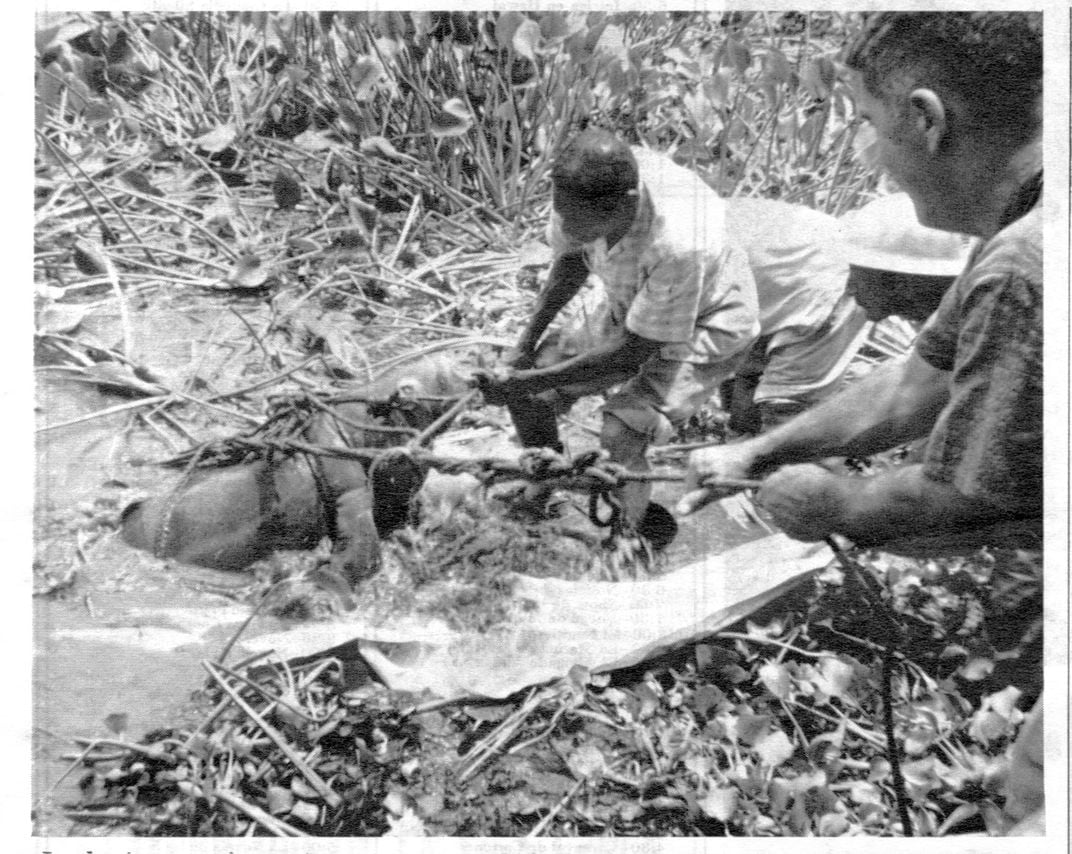

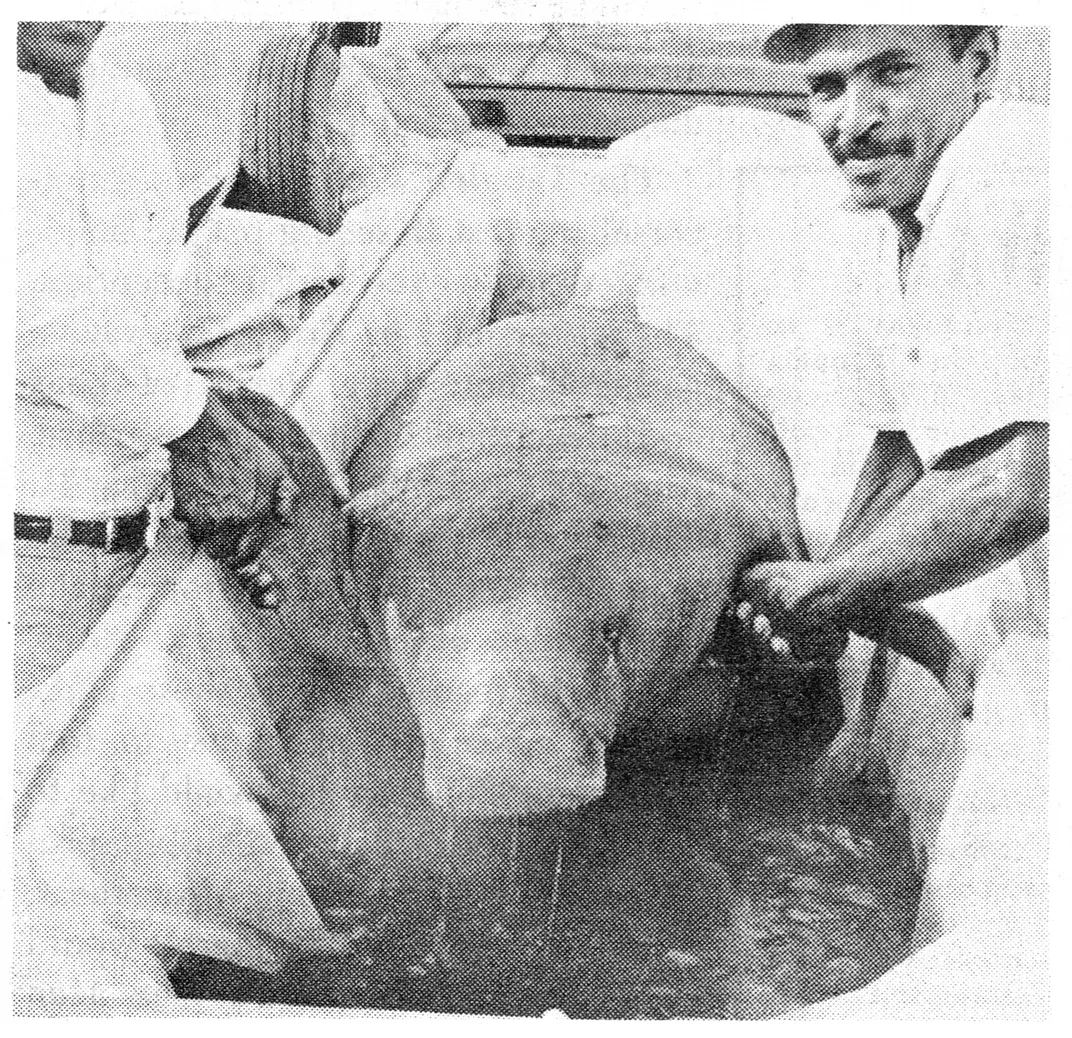

The first manatee to be flown to the Panama Canal was not from the Caribbean, as planned. It was a nonnative male Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis) from Peru. Nine other manatees were transported from the Bocas del Toro Province in northwestern Panama in C-47 cargo planes. The first two were females, which created the expectation of interbreeding, as “the fact that the new additions are female gave the Health Bureau manatee experts hope for a future population explosion in the manatee lagoon…”, according to a new article published in Marine Mammal Science.

Soon, several other T. manatus manatus individuals were flown in, including a pregnant female, and by the end of 1965, eleven manatees were freely feeding throughout the Panama Canal after the fence in the semi-enclosed area where they had been placed —“Manatee Lagoon”— was broken. Over 50 years later, in 2020, a manatee was sighted near the west Miraflores Locks, on the Pacific side of the Isthmus, prompting aerial and boat searches that were unsuccessful.

This event led marine ecologist Héctor M. Guzmán, and marine biologist Candy K. Real, from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, to ask themselves: “have Antillean manatees entered the Eastern Pacific Ocean?” In other words, has a marine mammal that is native to the Caribbean crossed over to an unfamiliar habitat —one where it has not lived for several million years? The answer is possibly yes. Since 1977, over 50 sightings have been reported between the Gatun Lake and the Miraflores Locks, located near the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal.

Even though the manatee program to control aquatic plant growth was abandoned shortly after its creation, given that thousands of them would be needed to achieve a real impact, the animals continued to be surveyed by what eventually became the Panama Canal Authority (ACP). In 2015, after an aerial survey, a population of between 20-25 manatees was estimated in the Gatun Lake.

“Although the possible passage is based on a single sighting in September 2020 made from a tanker, the idea is not far-fetched,” said biologist Martin Mitre from the ACP. “Manatees, although small in numbers, move freely around the lake, and some could pass through the locks.”

According to Guzmán and Real, it is unknown whether other manatees might have passed into the Pacific Ocean. However, it is possible. It is also best to prevent any more of them from crossing over through different management options.

“Ideally, the animals would be captured to prevent them from crossing over to the Pacific, with three options: return them to their native region (Bocas del Toro), isolate them within a safe lagoon of the Canal so that they serve to educate and promote tourism, or a combination of both,” said Guzmán. “But for that, we must first finish evaluating the size, distribution, and genetics of the current Canal population. We should support the ACP, which unfortunately inherited this historical mistake.”

The authors thank the Panama Canal Authority for the consent to publish this first record and for providing the permit to investigate the population status and distribution. Special thanks to Pilot Captains Eric Hendrick and Captain Ivo Quiroz Jr., Daniel Muschett, Angel Tribaldos, and Angel Ureña for the assistance and logistical support.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is part of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.