SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

How to Tell a Bird’s Age By Its Song

On Pipeline Road in Panama’s Soberania National Park, birdwatchers on high-end tours rack up two hundred bird species in a day and move on. But Corey Tarwater and Patrick Kelley have made it their life’s work to understand the daily melodramas of black-crowned antshrikes, first as students and now as faculty at the University of Wyoming. Meanwhile, their own family has grown to include not only 2 children, but a whole tribe of intellectual offspring.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/IMG_0810.JPG)

On Pipeline Road in Panama’s Soberania National Park, birdwatchers on high-end tours rack up 200 bird species in a day and move on. But Corey Tarwater and Patrick Kelley make it their life’s work to understand relationships between Black-crowned antshrikes, first as students and now as faculty members at the University of Wyoming. Meanwhile, their own family has grown to include not only two children, but a whole tribe of students, interns and volunteers.

On a warm morning in March, Panama project manager Laura Gómez and her newest intern, Michael Castaño, load their pickup for a bone-jarring ride into the forest, arriving at the Limbo Plot, a site famous among birdwatchers for the ongoing annual bird survey first conducted here 42 years ago.

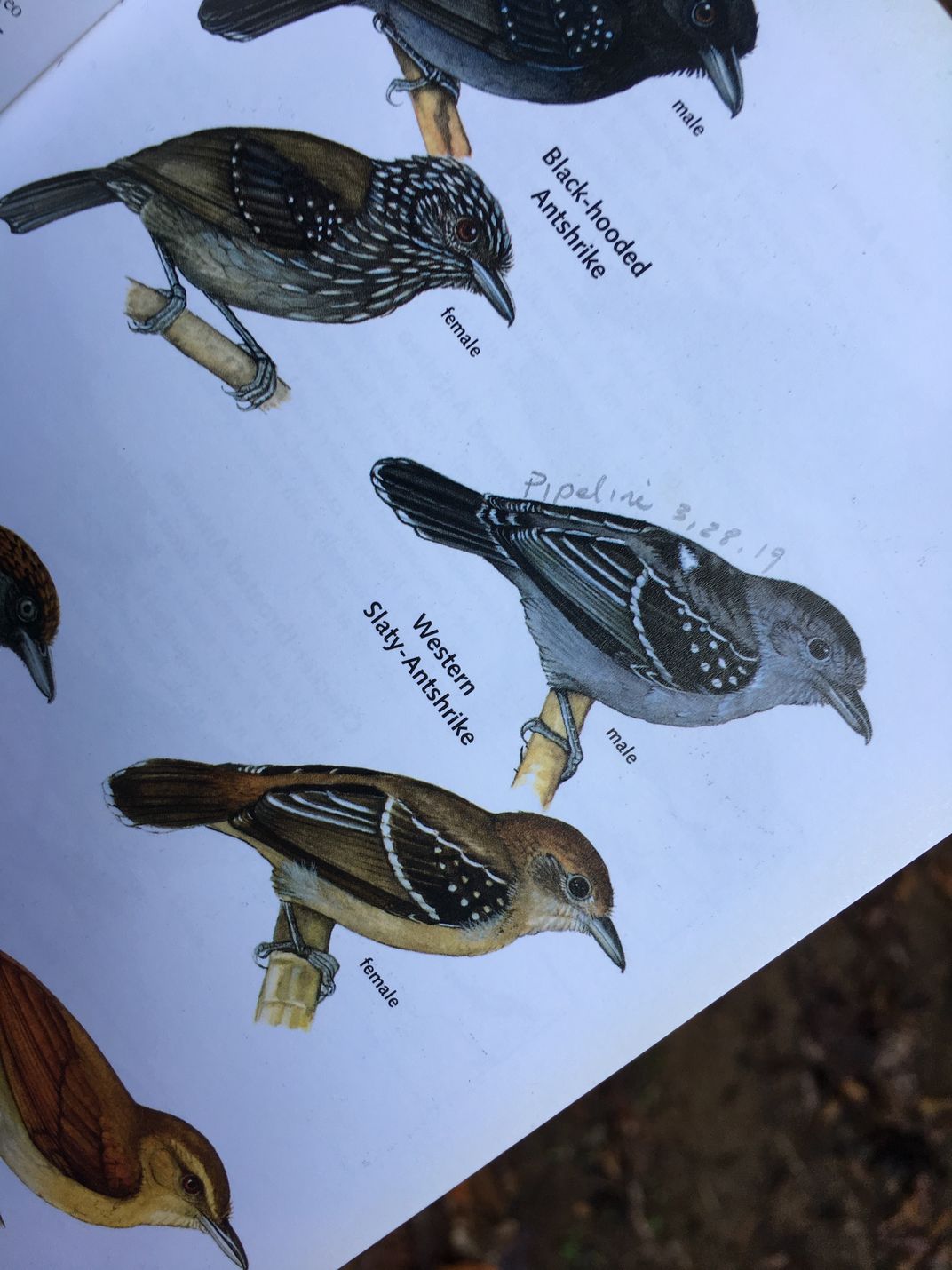

As Laura adjusts the harness of Michael’s digital recorder, the antshrikes are already calling: Uh-uh-uh-uh-uh-uh-ERK, the last note higher than the rest. Pairs sing year-round, aggressively defending their small territories.

“Corey and Patrick know so much about them,” Laura says. “They can estimate the age of any bird based on its song.”

Ghost intruders

Laura tromps through dry leaves to several points where she plays songs of birds of different ages. She’ll record nearby birds to find out if the resident pair in a territory responds differently depending on the age of the invisible intruder.

“About two months after young birds leave the nest they sing what we call the ‘loud song’ minus the ERK sound at the end,” explains Laura. “By 4-6 months they begin to include the ERK, but the song still sounds squawky.” When a juvenile is 6-8 months old, it sounds more confident.

An adult male defends his territory singing a deliberate, low-pitched loud song. Territorial males usually respond to a neighboring male’s loud song. Females may follow suit, first at low amplitude, ramping it up if the dispute persists. Birds that are particularly upset by intruders sing backwards: a chirr call that begins with ERK followed by uh.

“We think the birds may be more likely to answer playbacks of older birds because older males often pair with younger females on Limbo, but it is too early to tell.” First impressions often fail to hold up to data analysis. “We record the song using Marantz recorders and later we analyze the songs using an open source audio editor called Audacity to measure the number of notes each bird sings in a given time to determine its age.” Laura says.

Laura in Limbo

Howler monkeys and doves call in the background as Laura balances her wireless speaker on a branch and sets up her recorder: “We repeat the information that identifies a recording several times, at the beginning at the end, so that it’s easier to identify back at the lab.”

“I am Laura Gómez, it is March 28th, it is 7:55am. There are some clouds, maybe 20 percent cover, but it’s mostly sunny. This is Laura Gómez in Limbo.”

By doing these playback experiments, the group hopes to answer some intriguing questions: Are male territory holders more worried about older male intruders because their long-term female partner may prefer to mate with these males? Or are younger males more of a threat because they are males that usually try to usurp territory holders? Are the female territory holders more tolerant of these older male intruders, but not the young males? And how will the density of antshrikes and the quality of their habitat alter their response to intrusion?

As she sets up at the next site, Laura tells the story about how she came here from Medellin. Her first ornithology fieldwork was in Colombia. Then she had an opportunity to work in Manú National Park and Biosphere Reserve in the Peruvian Amazon. Realizing that to go to graduate school, it would be good to learn some more English, she applied to a job working for Corey and Patrick in Hawaii. At first there was no reply, but then her luck turned: she got an interview based on the recommendation of Patrick’s postdoctoral advisor, who had known her in Peru.

Later, she worked with another group on a bird census along the north eastern seacoast from New York to Maine and at a bird banding station in Pennsylvania called Powdermill—part of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. But when Corey found out she had funds for a long-term project in Panama in 2016, she called to offer Laura a job managing her field crew.

After the 9:43 a.m. playback at a site where there’s a lingering smell of peccaries, Laura says: “I think I’m on the border of two territories.”

Described as “very monogamous,” only a very few young antshrikes are sired by males other than their mother’s constant mate. Fathers provide extensive parental care, feeding their young for several months.

Eventually, after a year or so, parental patience runs out and the adults become increasingly aggressive, finally displaying the white patch of feathers on their back, normally hidden under their wings, to drive their kids out of their territory. The young birds may spend months “floating” from territory to territory until they find a mate and establish a territory of their own.

Murder

As we move on the intense dark eyes a capuchin monkey peers down at us from behind bouquets of rustling leaves far above. It pumps the branches back and forth with its arms as another capuchin runs up the trunk of a nearby sapling, balanced by the curl of its prehensile tail. Smart and short-tempered, the first hurls a stick at Laura, which she catches after it bounces off of several branches on the way down. White-faced capuchins, Cebus capuchinus, play villains in the ongoing antshrike drama.

Both the sound of young birds begging for food and the movements of adult birds as they provision the nest can attract the attention of a predator and increase the risk of nest predation. Parents brought more food in experiments when Corey played begging calls, perhaps as a way to quiet them.

Between 2004 and 2006, Corey videotaped predation by these monkeys, a snake (Pseustes sp.), keel-billed toucans, a double-toothed kite and a fasciated antshrike.

“Toucans are the worst,” says Laura.

As predators approach a nest, adults display aggressively, making a caw or a snarling sound while posturing and revealing a white patch of feathers that is usually hidden among the feathers on their backs. When her young fledgling is in imminent dangers, a mother may draw away a predator’s attention with a helpless warble call as she hops around feigning a broken wing.

Not very many young survive to fledge, but those that do have a good chance of surviving to adulthood. Once a young bird leaves the nest its chances of survival are about 75 greater than the average for young passerines in North America. Almost half of the antshrike fledglings survive to age one. However, they usually do not breed until they are two years old.

Thirst

Predators abound, but more nefarious forces are at work as climate change and development shrink the birds’ habitat.

Laura does playback experiments at 18 different sites including Paraiso, a town along the canal closer to Panama City. She wants to know if antshrike communities are organized in the same way in drier versus wetter habitat and in contiguous versus fragmented habitat and to find out how the age of birds affects how aggressively they defend their territories .

Paraiso is one of the smallest forest fragments in her study. In the national park, the antshrike territories are about 1 hectare on average. Antshrikes in big, protected areas may have more, smaller territories. Elsewhere, their territories may have to be bigger in order to access the resources they need to raise their young, but it will take more data to be sure.

This season’s cliffhanger—a life and death matter for the antshrikes—is about how long summer will last. More frequent El Niño events, longer dry seasons and more intense seasonal drought is bad news for tropical forest birds according to long-term research by Corey and her former advisor Jeff Brawn at the University of Illinois.

Members of the Tarwater and Kelly labs will be back to continue the long-term monitoring study. Laura will spend the next semester in the Tarwater lab at the University of Wyoming, where she will do her Master’s work. “I’ve seen snow before, but I’ve never made a snowman.” But she’s quick to point out that she’ll only have to endure part of the winter because she’ll be back next December for another field season in Panama as this team of birdwatchers follows their extended, singing family.