NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN LATINO

A Funeral for the Caribbean’s Native Extinction Hypothesis

Lawrence Waldron asserts that rumors of Taíno extinction are greatly exaggerated and definitely headed for an extinction of their own.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/IMG_0160_Did_they_resist_EDIT.jpg)

[Versión de este artículo en español disponible aquí.]

Let’s call it the “Extinction Hypothesis,” that centuries-old and stubborn notion that the Indigenous people of the Caribbean were wiped out by the Columbian Conquest, then “replaced” by people from Europe, Africa and Asia. According to the Extinction Hypothesis and its smooth-talking sibling, the Replacement Theory—which both still find a place in archaeological, anthropological and art historical scholarship—the Amerindians are gone, and the Caribbean is now a diasporic space, more satellite of Africa, Europe and Asia than center unto itself. In this peripheral Caribbean where the diasporas continue to work out their mestizo/creole identities and senses of belonging, practicing Amerindian ways or even being a biological descendant of Amerindians is not enough to be recognized as Amerindian. The standards of authenticity for people claiming to be Native are more stringent than for Rastafarians, Hindus or any other Caribbean group. For some scholars and laymen alike, the only authentic Indian is an extinct Indian. Owning a computer, listening to reggae or salsa, or playing baseball or cricket is enough to call into question one’s Taínidad or Kalinagoness. However, the exhibition “Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean,” on view at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in New York through November 12, 2019, asserts that ages-old indigeneity can be preserved and “reasserted [even] by mixed-heritage people.” In so doing, it measures and constructs the coffin (or weaves the burial hammock) for the Extinction Hypothesis.

“Taíno: Native Heritage” is not primarily a fine arts exposition like, say, the lovely and moving T.C. Cannon exhibition across the Custom House rotunda. Neither is it an old natural history museum-type presentation of artifacts from a bygone people with etic labels made by outsiders hovering above it. Rather, this is an exhibition that forges connections between the ancient and the contemporary, art and artifact, image and text, and the personal and the political.

As we snake through the connected chambers of the gallery, we go from a contextualizing map of the Antilles to a cluster of ancient objets d’art that ground us in the pre-Columbian—iconographically loaded, adorned ceramics, both slender and massive stone effigy belts (“stone yokes”), and a large example of those enigmatic trigonolitos (three-pointer stones) that are so unique to and emblematic of the region. Then it’s on to a screening room featuring a film made by the University of Leiden (from their Nexus 1492 project) on unbroken Taíno traditions in ceramics and basketry in the Dominican Republic. These are followed by sections that address in images, infographics and even a playful word cloud of common Taíno terms, the nature of the reckoning between conquest, race, mestizaje (the state of being of mixed heritage), migration and Taíno identity. It is not just that the Conquest happened to the Taíno but that Taíno technologies, domesticates, cuisine, and vocabulary have reshaped the world in which we live. The last two gallery chambers explore both traditional and post-modern expressions of Taínidad (i.e., Taíno-ness)—from the maguey hammock hand-woven by “Doña Esmeralda” Morales-Acevedo and the feather headdress by Kasike Jorge Estévez to volume one of Edgardo Miranda Rodríguez’s superheroine comic book, La Borinqueña, and the petroglyphic motifs on Bert Correa’s Taíno-futurist skateboard.

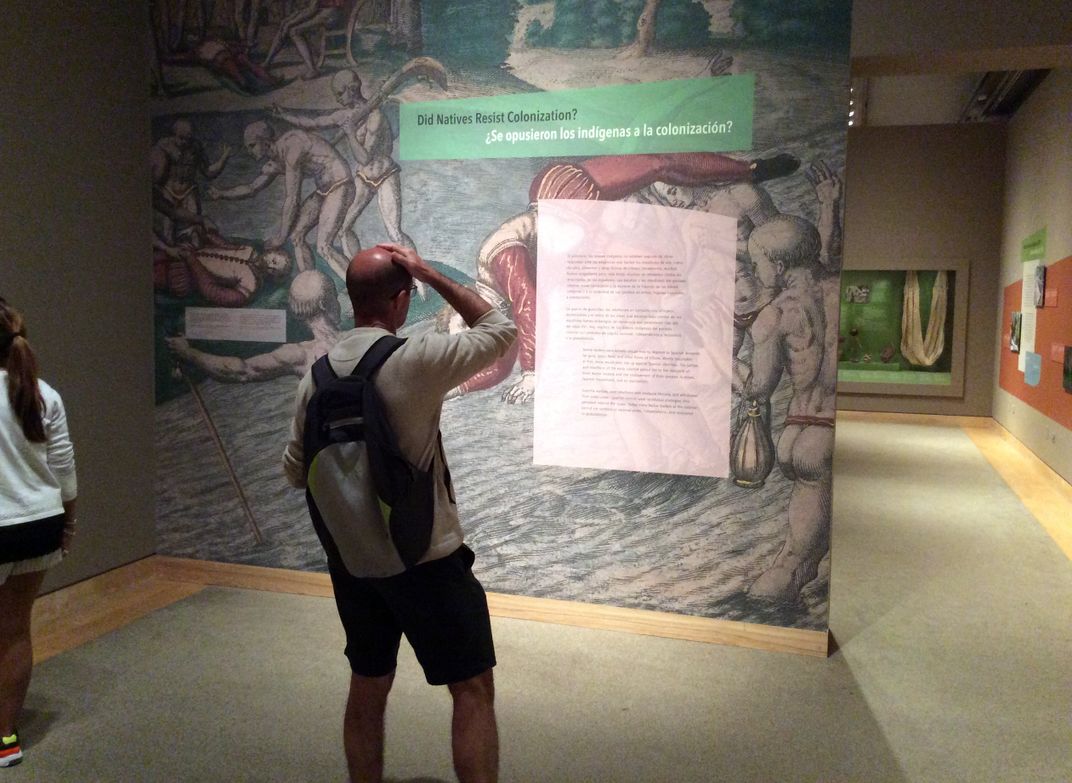

The gallery sections are all strung together by large, boldly colored text blocks and graphics that line the walls, often visible from the neighboring sections and thus conducting us along from point to point of interest. The brightly-lit, geometric chambers might not remind us of, say, the inscribed cave walls of Hoyo de Sanabe (Dominican Republic), dark and selectively lit for spotlight effect by hand-held torches (or smartphone flashlights), but they have a few functions in common with those grand, karstic caverns of the Greater Antilles—to educate, inspire and buttress the people with the power of their living traditions.

“Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean” was brought to the public through the collaborative efforts of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian Latino Center, specifically to reassess the living Native legacies of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and their U.S. diasporas. The engaging show is not just an exegesis upon but an unabashed expression of the knowledge, ideas and sentiments of the Taíno movement. This is a social phenomenon spanning some three decades that has brought into high relief the region’s rich Indigenous legacies, which are most evident in the Caribbean’s rural lifeways. Employing the archival and field research of credentialed scholars such as Native American studies specialist, Dr. José Barreiro (Taíno), and committed tradition-bearers and practitioners such as the aforementioned Jorge Estévez (Taíno), it demonstrates in material objects and (digitized) intangible traditions alike that rumors of Taíno extinction are greatly exaggerated and definitely headed for an extinction of their own.

Un funeral para la hipótesis de extinción indígena en el Caribe.

De Lawrence Waldron

Llamémoslo “la Hipótesis de la Extinción”, una noción tenaz con siglos de antigüedad que los pueblos originarios del Caribe fueron eliminados por la Conquista Colombina, y luego reemplazados por pueblos de Europa, África y Asia. Según la Hipótesis de la Extinción y su par, la Teoría del Reemplazamiento (ambos aún ocupan un lugar en las investigaciones arqueológicas, antropológicas y de historia del arte), los indígenas no están más y el Caribe se convierte en un lugar de diásporas, más como una satélite de África, Europa y Asia que un lugar con su propio centro. En este Caribe periférico donde las diásporas continúan negociando sus identidades mestizas/transculturadas y sus ideas de pertenencia, la práctica de modos de vida indígenas o aún ser un descendiente biológico de indígenas no es suficiente para ser reconocido como indígena. Los estándares de autenticidad para las personas que se identifican como indígenas es más riguroso que para rastafarios, hindúes o cualquier otro grupo caribeño. Para algunos estudiosos, así como para el público en general, el único indio auténtico es el que está extinto. Ser dueño de una computadora, escuchar reggae o salsa, o jugar béisbol o cricket es suficiente para cuestionar la veracidad de la identidad taína o kalinago. Sin embargo, la exposición “Taíno: Herencia e Identidad Indígena en el Caribe”, que estará abierta hasta el 12 de noviembre del 2019 en el Museo Nacional del Indígena Americano en Nueva York, afirma que la indigenidad puede mantenerse a través de los siglos y “ser reafirmada [hasta] por las personas de ascendencia mestiza”. De este modo, la exposición mide y construye el ataúd (o más bien teje la hamaca funeraria) para la Hipótesis de la Extinción.

“Taíno: Herencia Indígena” no es principalmente una exposición de arte, como por ejemplo la bella y conmovedora exposición del pintor T.C. Cannon, que se exhibe al otro lado del museo. Tampoco es una muestra de artefactos de algún pueblo desaparecido al estilo de los anticuados museos de historia natural. Más bien, ésta es una exposición que forja conexiones entre lo ancestral y lo contemporáneo, arte y artefacto, imagen y texto, y entre lo personal y lo político.

A medida que se circula por las salas de la exposición, primero nos orientamos con un mapa de las Antillas y luego pasamos a un ensamblaje de artefactos que nos anclan en tiempos pre-colombinos—cerámicas adornadas con abundante iconografía, aros líticos en ambos estilos delgado y grueso, y un ejemplo grande de los enigmáticos trigonolitos que son particulares a y emblemáticos de la región. De ahí, pasamos a una sala donde se muestra una película hecha por la Universidad de Leiden (de su proyecto Nexus 1492) sobre la continuidad de tradiciones de cerámica y cestería taínas en la República Dominicana. Estos están seguidos por secciones que, mediante imágenes, infografía y hasta una lúdica nube de palabras comunes de origen taíno, exploran la relación entre conceptos de conquista, raza, mestizaje (la condición de ser de descendencias mixtas), migración y la identidad taína. No solo que los taínos pasaron por la conquista, sino que la tecnología, agricultura, tradiciones culinarias y vocabulario de los taínos han formado el mundo en que vivimos. Las últimas dos salas exploran expresiones tradicionales y posmodernas de taínidad—desde la hamaca de maguey de Doña Esmeralda Morales-Acevedo y el penacho de Kasike Jorge Estévez hasta el primer volumen de La Borinqueña de Edgardo Mirando Rodríguez (una historieta de superheroína) y la patineta con diseños de petroglifo en estilo taíno-futurista de Bert Correa.

La exposición está articulada por grandes y coloridos bloques de texto y gráficas que cubren las paredes, y que son frecuentemente visibles desde secciones adyacentes de manera que nos guían entre los distintos puntos de interés. Aunque las salas geométricas con amplia luz quizás no nos recuerden a las paredes pintadas de la cueva de Hoyo de Sanabe en la República Dominicana, cuya oscuridad se ilumina selectivamente con antorchas (o linternas de teléfonos celulares), sí tienen algunas funciones en común con esas grandiosas cavernas kársticas de las Antillas Mayores—educar, inspirar y alentar a las personas con el poder de sus tradiciones vivas.

“Taíno: Herencia e Identidad Indígena en el Caribe” fue presentada al público gracias a los esfuerzos colaborativos del Museo Nacional del Indígena Americano y el Centro Latino Smithsonian específicamente para repensar los legados indígenas vivos de Cuba, la República Dominicana, Puerto Rico y sus diásporas en Estados Unidos. Esta exposición cautivadora no es solo un ejercicio intelectual sino una expresión audaz del conocimiento, ideas y sentimientos del movimiento taíno. Este fenómeno social con más de tres décadas ha destacado los ricos legados indígenas de la región, que son más evidentes dentro de los modos de vivir rurales. Utilizando las investigaciones de archivo y campo de estudiosos reconocidos como el especialista en estudios indígenas Dr. José Barreiro (taíno) y practicantes y portadores de tradiciones comprometidos como Jorge Estévez (taíno), mencionado previamente, la exposición demuestra con objetos materiales y tradiciones intangibles digitalizadas que los rumores de la extinción taína están gravemente exagerados y definitivamente en camino hacia su propia extinción.