Equipping the Next Generation of Radical Optimists in an Era of Uncertainty

A new series of creativity and critical thinking exercises from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum offers educators prompts, visuals, and big ideas to support student reflection and speculative thinking.

:focal(800x800:801x801)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/a6/17a6bbcf-4790-4975-a617-be4616cb9fd3/chsdm1.jpg)

Between quarantines and the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, powerful moments of protest, and a collective witnessing of the already occurring effects of climate change, it’s more important than ever to connect and evaluate how we respond to the world around us. The effects of these simultaneous crises on our students can’t be ignored. As educators, it is our job to empower students, to spark conversations, and to create space for reflection and creative world-building.

Given this, how might we as museums and educators build students’ creative and social-emotional toolkits to help them proactively envision a better world? As a museum whose mission is to educate, inspire, and empower people through design, we recognize that designers do not see the world as it is, but as it could be.

Different communities have developed ways of responding to the world around them. One such method is the genre of Afrofuturism. With its roots in African American science fiction, Afrofuturism is a genre and cultural expression that fills the gaps where people of color have been left out of the narrative. It combines fantasy, science fiction, African traditions, and speculative thinking to analyze the past and present to build worlds that interrogate or abolish racialized colonial structures and celebrate Blackness and Black culture through film, fashion, dance, music, visual art, and literature. Examples of Afrofuturism include the literary works of Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemisin, the music and aesthetic of artist Janelle Monae, and the comic series and 2018 Marvel film, Black Panther.

The recent opening of Jon Gray of Ghetto Gastro Selects at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum presented a unique opportunity for Cooper Hewitt’s education department to experiment with storytelling through the Learning Lab platform, the Smithsonian-wide digital resource where users can access collections that feature museum objects, videos, activities and more. Jon Gray, the co-founder of Ghetto Gastro, a Bronx-based food and design collective, selected objects from Cooper Hewitt’s collection — many related to Black culture and history — and re-interpreted them through an Afrofuturist narrative. Brooklyn-based artist and educator Oasa DuVerney was commissioned to create drawings bringing the narrative of Jon Gray of Ghetto Gastro Selects to life.

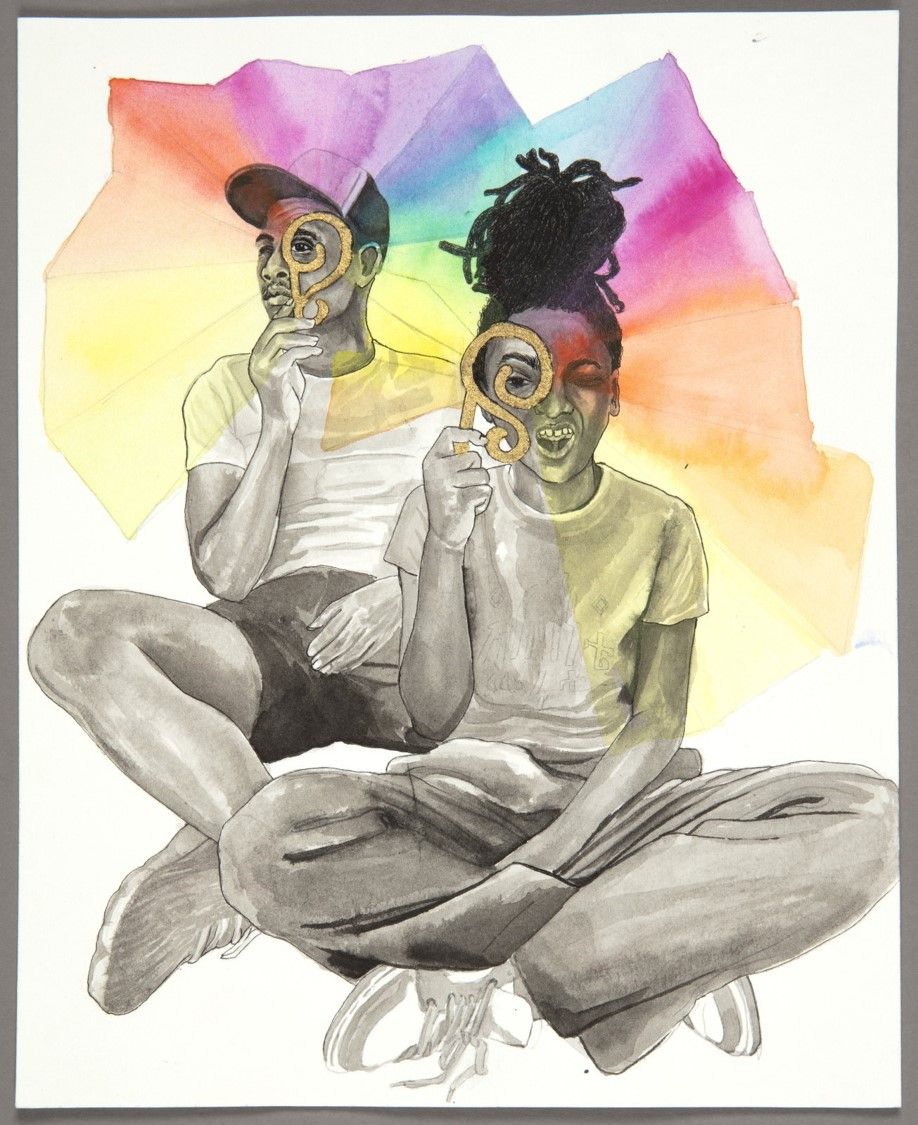

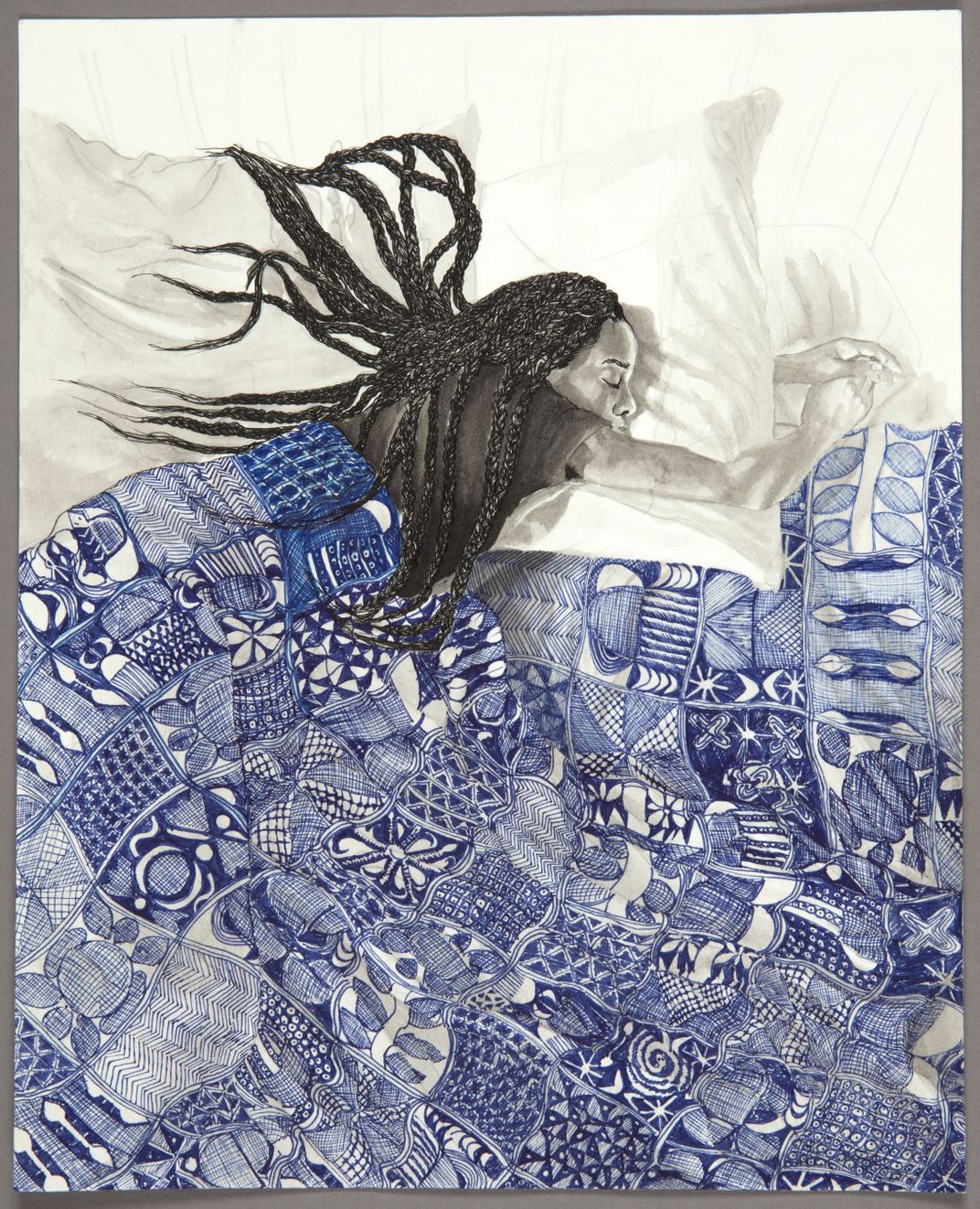

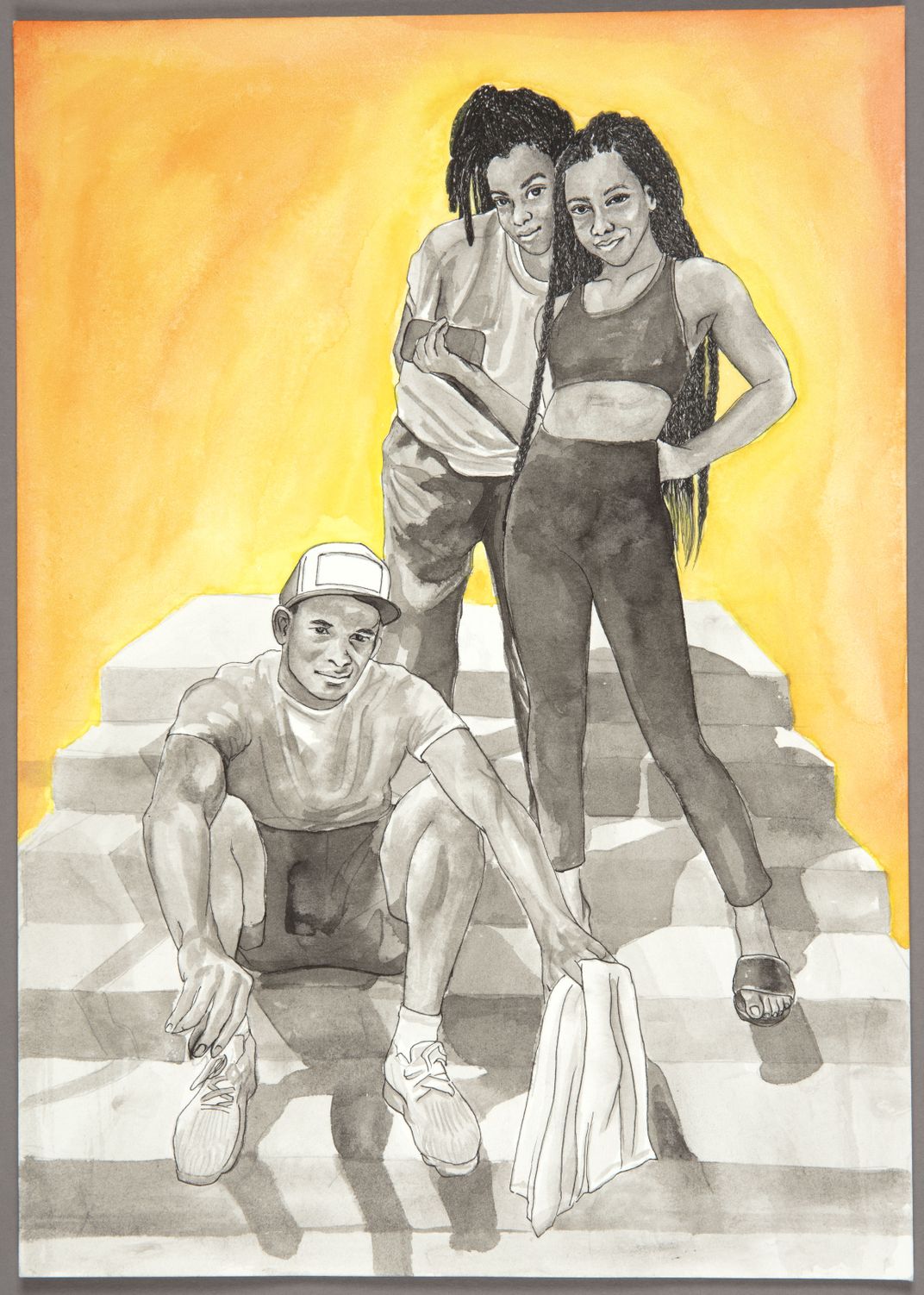

Cooper Hewitt’s Education department then commissioned DuVerney to create additional drawings to be featured in a new Learning Lab series, titled I Saw Your Light and It Was Shining. The title of this project, "I Saw Your Light and It was Shining," is from the poem Rhinoceros Woman by writer and Black Liberation Army activist Assata Shakur. This poem influenced DuVerney's thinking in creating the original drawings, which were inspired by objects from the exhibition and influenced by the belief that through speculative storytelling, we can adapt, dream, and heal. DuVerney’s drawings reinterpret objects from the exhibition through the lens of her teenage children’s experiences during the unrest of the summer of 2020. Through these collections, it was also DuVerney’s desire to reframe and critique objects and museum experiences.

Below we provide a quick introduction to three of the collections from the I Saw Your Light and It Was Shining series and how they can be used to spark conversation and reflection with students.

The first collection, I Saw Your Light and It Was Shining, can be used for students to imagine the world they want to see and be a part of. Through this exercise, we make space for speculative thinking, learn about student interests, and generate stories. What might these imagined worlds say about the student’s present?

Essential Questions:

-

What does it mean to see?

-

What does it mean to be seen and to see others?

-

What does it mean to change your perspective?

Build on these concepts with students:

-

Begin with three objects. They can be familiar or unfamiliar.

-

Ask students to look closely, perhaps drawing or sketching, and combine the three objects.

-

What new object have they created? How might this object be used in 50 years to address a global or societal issue? Ask students to share their objects and the stories connected to them.

Learn more about this exercise via our September 2021 Smithsonian Educator’s Day archived session.

Next, the collection, Rest as Resistance, can be used to investigate the power and importance of rest, especially when engaging in activism or discussing challenging topics.

Essential Questions:

-

How might we think about and care for our mental health?

-

What helps you to relax, recharge, and feel creative?

-

How might you recognize when someone close to you needs help? How might you support good mental health in others?

Build on these concepts with students:

-

In a group, ask students to come up with a list of adjectives- what does good mental health look like to them?

-

From here, ask each student to contribute one activity that helps them relax, recharge or feel creative. Create a class book, anchor chart, or zine for students to return to and put it in a place that everyone can access.

-

Make this a habit: ask students to try to recognize when their peers need help and use these strategies to help them support one another.

Finally, the collection, Returning the Gaze, can be used to tackle challenging objects and think about the ways we might reshape the world in a way that better reflects ourselves and our communities.

Essential Questions:

-

What are (at least) five things people should know about you?

-

How do you recognize and celebrate the individuality of the people around you?

-

If you encountered an object that negatively reflected you or your culture, how might you respond and why?

Build on these concepts with students:

- Ask students to reflect on what traits make them feel the most confident in who they are. In pairs, ask students to share—what similarities might they discover?

- With these answers in mind, ask students to reframe, redesign, or remix an existing object or work of art in their own image. What did they change, and why?

When we encourage students to think speculatively, we allow them to break through expectations and see possibilities that could be. The practice of speculative thinking can act as a light in the dark: it can sustain us, it can bring forth new ideas, and it can be radical in its optimism.