Changing the Game with Game-Based Learning

Learn how museum educators at the Smithsonian are going all in with game mechanics for learning and embracing the playful, experimental side of education through the structure of familiar games.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Game_Based_Learning.png)

Learn how museum educators at the Smithsonian are going all in with game mechanics for learning and embracing the playful, experimental side of education through the structure of familiar games.

How might we instill 21st century skills like creativity and problem-solving in students of all ages? How might we explore complex topics like evolution with museum visitors in person and online? How might we engage students in learning about topics that seem out of reach?

Questions like these have guided Smithsonian educators to embrace games as tools for learning. Simply put, educational games work because they make learning fun. Several studies show that students are likely to be more motivated during game-based learning activities. According to recent research published by the Journal of Educational Psychology, incorporating elements of game design as learning strategies can lead to increased student engagement and knowledge retention.

In practice, implementing games in educational settings can take many forms, and at the Smithsonian, educators have used the pedagogy of game-based learning to create innovative programs and activities that open the door to our vast content and collections for learners of all ages.

At the National Museum of Natural History, we have found that the more game-like we can make our opportunities to interact with our collections, the more engaged our visitors will be. In Q?rius, The Coralyn W. Whitney Science Education Center, for example, we have self-guided, collections-based activities set up on tables that borrow heavily from game design. Not only do they encourage visitors to take action--observing and physically moving objects and props--we work very hard to make the presentation attractive and fun, appealing to visitors’ senses, and to make the directions and set-up so clear that visitors know instinctively what to do without instruction.

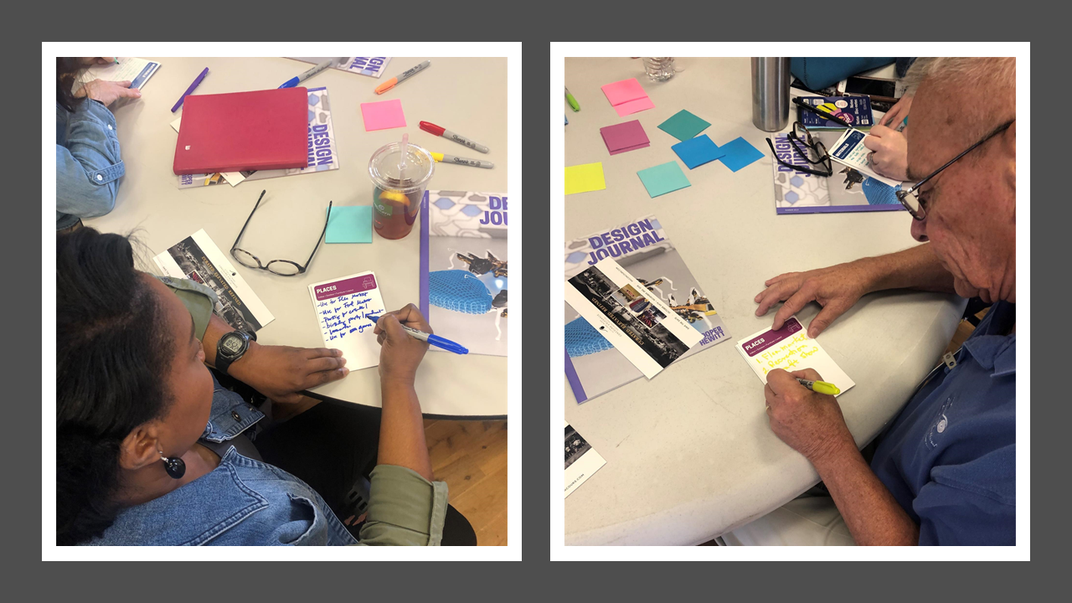

A game-based approach works equally well in a facilitated learning environment. At Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, we know that to successfully teach seemingly intangible soft skills like imaginative thinking, problem solving, and curiosity, providing a tangible structure as a guardrail allows for more creative thinking. Because learners are familiar with the rules and constraints of games, using these structures as a starting point leaves space to focus on content and creativity. In 2017, we began prototyping a brainstorming game using the familiar constraints of Scattergories, a game which asks players to come up with words beginning with a common letter in response to a series of prompts. The player with the most unique words wins. Inspired by this game’s objective of favoring the most unexpected or surprising words, we developed a similar game which begins with a common problem (i.e. a student with a broken leg must get to her second floor classroom). Players come up with unusual new ways to solve this problem within the constraint of a category. How might this problem be solved with technology? With new materials? Through new processes?

At the National Museum of Natural History, we’ve taken this approach of borrowing from game design even further with some of our new activities in the Deep Time Hall, where visitors compare fossil bones of elephant relatives, whale relatives, and bird relatives and use observations of shared characters to place pawns representing those species in their appropriate spot on evolutionary trees. Presenting the trees on colorful game boards, with tokens and toys representing the animals and their traits transforms what is often considered a dry, abstract concept into a fun puzzle for families to solve together.

Using games to teach other abstract concepts- like how to “think outside of the box”- has also worked well at Cooper Hewitt, specifically in our Build-Your-Own Design Brief activity, which we have applied in virtual and in-person settings. Originally developed for high school students, our goal was to create a workshop that would teach students how to both brainstorm ideas in response to a design brief and communicate those ideas to a team. The challenge was creating a workshop that was both fun and educational. Using a structure similar to Mad Libs, we developed a series of open-ended prompts for students to answer, like “a mode of transportation” and “a place you have never been”. The answers to these prompts revealed a unique, open-ended, and often funny design brief (i.e. Design a boat with four wheels to get Mickey Mouse from the school cafeteria to Jupiter).

The success of Cooper Hewitt’s Build-Your-Own Design Brief activity is partly in that it intentionally encourages students to embrace wild, seemingly impossible solutions because the problems they are solving are made up. By removing the pressure of the real world, students learn to flex their creative muscles and develop problem solving skills that can later be applied to complex real-life problems. In many learning environments, students are often asked to find the “right answer”. But there are often several “right ways” to solve a problem. The Build-Your-Own Design Brief’s open-ended structure gives students a chance to find unusual, unprescribed solutions, and practice moving through a process of creativity which deemphasizes the end product.

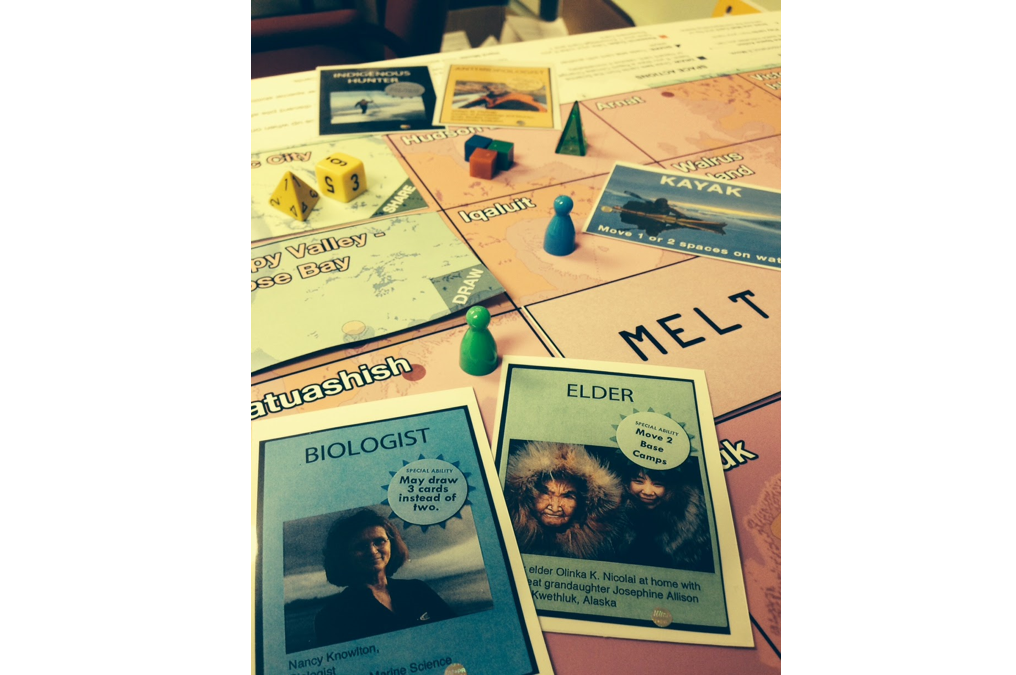

Similarly, at the National Museum of Natural History, we have intentionally kept a board game called Arctic Race in prototype mode because we have found it encourages deeper involvement and thinking if the players know they have a chance to affect the design. In Arctic Race, modelled in part on Forbidden Island and Pandemic tabletop games, players collaborate to gather skills and knowledge before areas in the Arctic change irrevocably due to climate change. Once we had some basic mechanics and game pieces in place, with the help of local Washington, D.C. game store experts Labyrinth Games and Puzzles, we opened it up to kids and families, using it with school groups and in family game nights, always with space allowed to get feedback for making changes. These players have given us fantastic ideas for improvement, some of which we’ve been able to implement and many that we’d like to if we could get more funding. But the main lesson for us as educators is that creating and riffing off games provides fun, creative, focused learning for all ages. Once you open up those possibilities to kids with prompts like, ”How else could we play this?” and “What other content could we use?” they jump in and own their creative learning experience in exciting ways.

Introducing games as an educational tool can take many forms- and need not be limited to a traditional learning environment. What games already exist on your shelf that can be adapted? What rules of play can be tweaked- or even broken- to draw out creativity and innovation in the students in your life? Check out the recommended links below, and share your own ideas with us on social media using #SmithsonianEdu!

-

Lineage Evolution Activities, including "Elephant Evolution," "Whale Evolution," and "Tiny Fossils"