SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Struggle for Native Lands in Indianola, Washington

Indianola’s beaches were once the home of the Suquamish Tribe, or in their language, Southern Lushootseed, suq̀wabš—People of Clear Salt Water.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/indianola-dock.jpg)

“We would like to begin by acknowledging that the land on which we gather is within the aboriginal territory of the suq̀wabš — ‘People of Clear Salt Water’ (Suquamish People). Expert fishermen, canoe builders and basket weavers, the suq̀wabš live in harmony with the lands and waterways along Washington’s Central Salish Sea as they have for thousands of years. Here, the suq̀wabš live and protect the land and waters of their ancestors for future generations as promised by the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855.”

—The Suquamish Tribe Land Acknowledgement

Growing up on an island in Washington State, I spent my childhood exploring the waterways and inlets that make up the Puget Sound. A number of times I visited a town called Indianola, about ten miles northwest of downtown Seattle. It’s small—a cluster of beach houses in a thick second-growth forest. About 3,500 people live in this model tight-knit, middle-class community. I remember clearly the overwhelming beauty of the area. From the dock stretching out into the water, you can see the Seattle skyline, the snowcapped Olympic Mountains, and iconic Mount Rainier. The strong salty brine of the sound fills the air, a constant reminder of the beach’s presence.

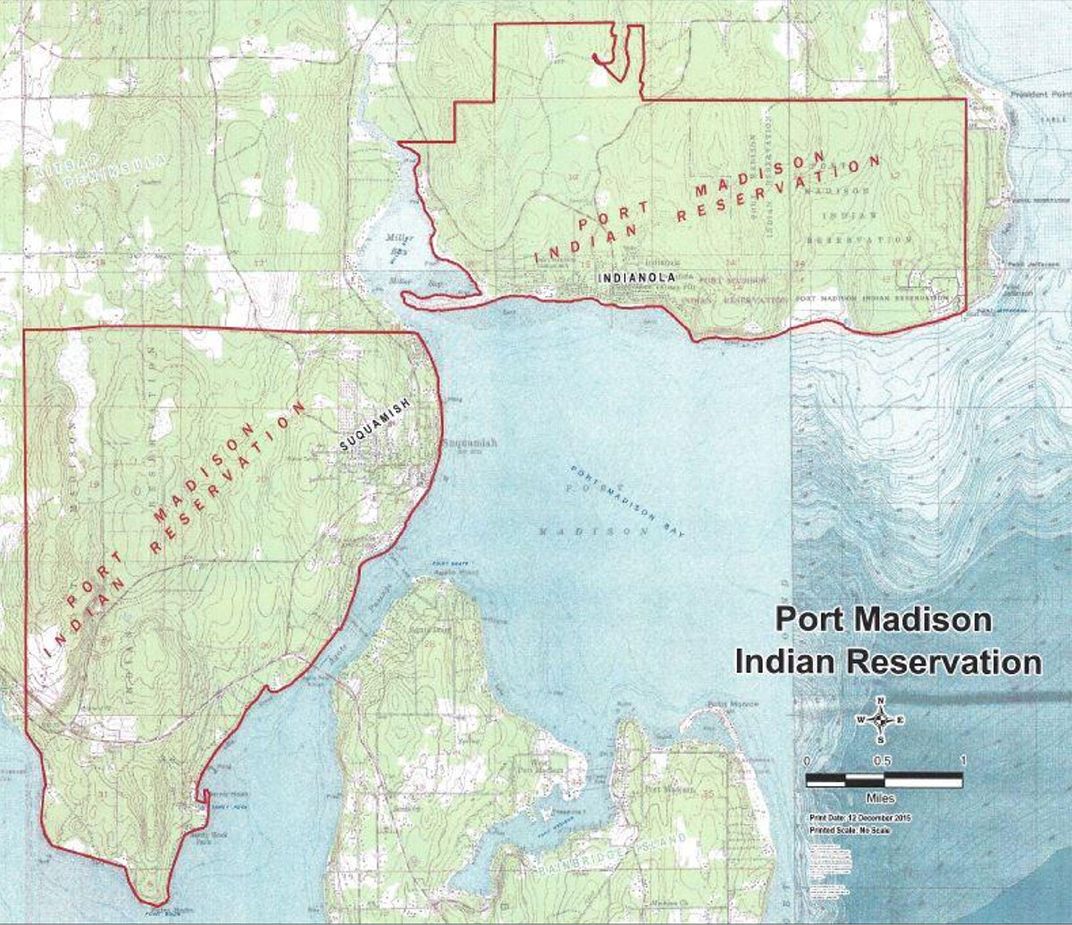

I only recently learned that the town is located within the boundaries of the Port Madison Indian Reservation and that the town’s residents are almost completely non-Native.

Indianola’s beaches were once the home of the Suquamish Tribe, or in their language, Southern Lushootseed, suq̀wabš—People of Clear Salt Water. Today, the Suquamish live in towns dispersed throughout the reservation, created in 1855 by the Point Elliot Treaty, which allotted them 7,657 acres of land. Only fifty-seven percent of that land remains Native-owned. The first non-Native residents arrived in the early 1900s, and ever since a sharp divide has existed between the Suquamish and non-Native communities. Today, there is little, if any, public acknowledgement that the town sits on an Indian reservation.

Above is the Suquamish Tribe’s land acknowledgement. It’s meant to bring awareness to the existence of the Suquamish people, although many Suquamish see public recognition of this sort as the bare minimum.

“Land acknowledgements do not do a lot for Native people,” says Lydia Sigo, a Suquamish Tribal member and curator at the Suquamish Museum. “There needs to be some kind of saying like ‘honor the treaties,’ because that is something concrete that non-Native people can do to support tribes. Without these treaties being honored, the U.S. doesn’t even have land to govern. It’s squatting illegally until it honors the treaties that are enshrined in the Constitution.”

Some people in Indianola are at the beginning of a journey to examine the history that surrounds the land on which they live.

The non-Native families who reside here have legal rights to the land, but the circumstances leading to this ownership involve colonialist alterations to the law and manipulation of a people unfamiliar with Western ideas of ownership. Thinking about history in this way challenges the Western concepts of land entitlement and exposes alternative paths for the future.

“By the time you bought your land, how many hands had it passed through?” says Janet Smoak, a non-Native director of the Suquamish Museum. “People use this idea to absolve themselves from the colonization story—‘it wasn’t really you who did this.’ In reality, history doesn’t end at a certain moment in time and start over again. Those threads keep pulling through.”

Understanding the history of how this situation came to be reveals the problematic nature of the relationship between the Suquamish people and the non-Native residents of Indianola.

Lawrence Webster was a respected Elder and Tribal Council Chairman of the Suquamish Tribe who grew up in the neighboring town, Suquamish. In 1990, a year before his death, he gave an interview addressing life on the reservation in the early 1900s and the U.S. government.

“I was born in 1899,” Webster said. “The first white man I saw was the sub-agent who came into Suquamish in about 1900. I found out they’d sold half of the village for a fort to the Army with the promise that if they never built a fort there that it’d be returned to the Suquamish Tribe. The Indians moved off in 1906—they had to get off from there and go to homesteads. So we came over here to Indianola.”

Although the Army never built the fort, they soon sold the land to non-Native developers for beach homes instead of returning it to the Tribe.

The sub-agent and his family resided in Indianola with the Suquamish residents to watch over the area for the federal government and enforce the prohibition of traditional Suquamish ways of life.

“The sub-agent helped us build some houses, but they made sure that the ceiling was low so that we couldn’t practice our ceremonies,” says Marilyn Wandrey, a Suquamish Elder born in 1940, the daughter of Lawrence Webster.

The town was not in the hands of the Suquamish for long.

“The head of each family got 160 acres of Tribal Trust Land, but in the late 1800s ’til the 1940s, those Indians could sell their land off for nothing,” Ed Carriere says. Carriere is a Suquamish Elder, master basket maker, and the only Native person to still own waterfront property in Indianola. He was born in 1934.

What Carriere is referring to is the federal Dawes Act of 1887. Together with the federal Burke Act of 1906, the legislation allowed non-Natives to buy Tribal Trust Land if the natives who owned that land were deemed “incompetent.” The sub-agent determined that from something as small as not being able to speak English or being elderly. Developers, such as the Indianola Beach Land Company owned by Warren Lea Gazzam, started to buy up this land to build houses.

“In 1910, the government started selling the allotments of the Indians that were ‘incompetent’ or didn’t have a way of making a living,” Webster explained. “They advertised and sold it. Some of the allotments were sold without the Indians even knowing it. They gave them $25 a month per person for their land until the money was used up. Some of them used up their money and didn’t ever know where to go. They had to go on some relation’s land and build a house.”

In 1916, the Indianola Beach Land Company built a ferry dock to welcome prospective land buyers from Seattle. Over the decades, an influx of non-Native people crossed the water in search of an escape from the city. To them, the beautiful beaches of the reservation met all the criteria. While some Suquamish were forced to sell their land because they were deemed “incompetent,” others were forced to sell just to eat.

Carriere’s great-grandparents sold about half of their land to developers, but they managed to maintain ownership over a parcel that today is the last Native-owned property on the Indianola beach. They were able to maintain this ownership and provide for themselves by working for non-Native people.

“My grandma and I had to live off the bay—fish, clams, ducks, whatever we could find,” Carriere says. “We had to make our living by either doing odd jobs for non-Native residents, digging and selling clams, selling fish, any type of work that we could do. It was very hard to eke out a living that way.”

In the early 1900s, all of Indianola’s Tribal families were forced to send their children to government boarding schools, where they were chastised for speaking Southern Lushootseed and forbidden from practicing their way of life. After separating the children from their families and community, the schools forced them to learn English and Western traditions and trades. This was central to the systematic government effort to erase the Suquamish culture.

“My great grandma never taught me our language because she was punished for speaking it in boarding school,” Carriere says. “I tried to learn it later, but it didn’t stick. There wasn’t any emphasis on song, dance, or artwork when I was growing up. I practically didn’t even know that there was a Tribe.”

Today, the divide between the Suquamish and the new non-Native residents runs deep. Only a handful of Native families have remained in town since the early 1900s.

“Over the years, as I was a teenager being raised in Indianola, I noticed that I was on the reservation and that the white people that lived near me were separated from us,” Carriere remembers. “They had a lifestyle that was so foreign, so different to our lifestyle. There was a complete separation.”

For the town, this separateness and the history that led to it is an uncomfortable, unacknowledged truth.

“As a child growing up in Indianola, it wasn’t very apparent to me that I was on an Indian reservation with very few Indians. I didn’t think about that,” says Lisa Sibbett, a non-Native who grew up in Indianola in the 1990s.

Most Indianola residents are ignorant of the town’s colonial past. Children are taught little about the historical context surrounding the land that their houses sit on, allowing that past to continue into the present.

In the mid-1980s, the Tribe planned to buy land in Indianola with the intention of building affordable housing for Tribal members.

“Some of the residents were very angry,” says Suquamish Elder Marilyn Wandrey. “They didn’t want the Indians to be building homes there, so they talked the landowners out of selling it to the Tribe. There was so much hate.”

Eventually, the Tribe was able to purchase another piece of land and build the affordable housing there. In order to foster connections between these new Native residents and the rest of the Indianola community, the Tribe reached out to the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker social justice organization that operates across the United States to foster peace and mediate conflicts. At the time, Wandrey was a member of this group and volunteered to help organize a way forward.

“The plan was to bring some friendly people from Indianola together with the Tribal family members that were going to move into those homes,” Wandrey says. “I organized a number of those meetings, and eventually they came up with three committees.”

Between 1989 and 1990, the communities joined forces to build a public baseball field, perform a land blessing ceremony, and conduct twelve interviews with both Native and non-Native Elders of Indianola.

“I met some really awesome people,” Wandrey says. “There were so many that came forward that wanted to help. There’s not many left now, but I made quite a few friends.”

Over the last thirty years, the work of these people faded. As death claims the friendships that were made in the 1990 project, only a few close relationships between the Tribal community and non-Native Indianola residents remain.

In July 2020, another conflict unsettled the two communities. The Indianola Beach Improvement Club hired a security guard to monitor the Indianola dock and put up signs declaring the beach off-limits to all non-residents. For the Native people of the Puget Sound, the beach has been the center of community life since before colonizers ever set foot on U.S. soil, and now they are not welcome.

A small group of non-Native property owners in Indianola invited Robin Sigo, a Tribal councilwoman, to an Indianola community meeting, to talk about beach access. Some were excited to learn about the beach’s history, but many were unreceptive.

“It didn’t go very well,” says Melinda West, a resident of Indianola since 1980. “I didn’t feel like Sigo was respected for what she was bringing. She tried to bring more of the Suquamish experience of the Indianola beach to these people. But some of the people at the meeting were only there because they’d owned beach land since 1916, and they didn’t want other people sitting on their logs. They were very vocal.”

In response to these attitudes toward the Suquamish people, a small group of residents came together to form a group called the Indianola Good Neighbors. Their goal is to educate people about the history of Indianola and to connect the Tribe and town once more.

“We in Indianola have a lot of work to do around racism and our relationship with the Suquamish Tribe,” says Janice Gutman, one of the group’s founders. “Of course, our country being in upheaval around issues of racial justice played a part. So, I sent out a letter inviting friends and neighbors to come together and figure out what we can do.”

The Indianola Good Neighbors formed into committees. One group is advocating for replacing the “Private” signs with new ones that commemorate the Native history of the beach. Another group is putting up signs throughout the town to educate people on the uncensored history of land ownership in Indianola. Another is partnering with a realtor to investigate ways of returning land to Native hands.

A separate group of residents, headed by Paul Kikuchi, Marilyn Wandrey, and Melinda West, is recovering the interviews from 1990 and preparing them to be archived in the Suquamish Museum. These oral histories reveal how the Suquamish people worked with the beaches for their food as well as building materials. One of the Elders interviewed was Ethel Kitsap Sam.

I was born and raised in Indianola. And when I grew up to be about six years old, my grandmother and I used to go clam digging all over the beaches. No white man, nothing. She would never have money. We just traded for deer meat and dry salmon.

We’d camp out there at Port Orchard. We’d camp out in the open, no tent or nothing. Just make a big bonfire and sleep right there by the fire. Next day we’d wait for the tide to go out and then my grandma would dig clams. I must have been too young to be digging. I used to just play on the beach. She used to roast the crabs by the fire too. She’d get the ashes and put the ashes over the crabs to cook it. We didn’t have a pot to cook it with—just used the ashes.

The Suquamish Museum is located in nearby Suquamish, a fifteen-minute drive from Indianola. Curators will mine these interviews to educate the public on the history of the area.

After learning more about Indianola’s past, Lisa Sibbett joined the Indianola Good Neighbors group’s Decolonization Committee, focused on finding ways of compensating the Tribe for the stolen land.

“I’m somebody who potentially stands to inherit land in Indianola from my parents,” Sibbett says. “I thought, would it be possible for, when a generation dies, instead of handing their property to their children, return it to the Tribe? Decolonizing is not just about decolonizing minds. It’s about decolonizing land and waterways.”

Recently, a number of Indianola residents committed to willing their land to the Tribe after they pass. “We want to find a way to pass our land back to the Tribe,” says Sarah White, a current resident. “Every day we feel grateful and aware that we are only stewards. We do not know what this will look like yet, but our intention is to honor the treaties and return this land.”

Sibbett is currently working with the Tribe’s realtor to educate non-Native residents on their options if they choose to give their land back. “It’s a scary thought,” Sibbett says. “The thing that makes it feel more doable is that there is a way to give ownership of the land to the Tribe but allow the descendants of the people who returned the property to continue to use it. The Suquamish people have stewarded this land until this point. I think the Tribe should have autonomy and sovereignty over what is done with the land, which was promised to the Tribal people in their treaties.”

For a less intensive form of compensation, many Tribes across the United States have a system in place to receive monthly donations from non-Native people who live on land that used to be stewarded by the Tribe. Some call it a land tax, or Real Rent. “We just have to find the scale that we’re comfortable with and then push ourselves a little bit,” Sibbett says.

The Indianola Good Neighbors group’s recent steps to improve relations between Native and non-Native residents are still in their infancy and only include a small portion of the Indianola community. “Every time that there is work to be done, it brings community members together,” Janet Smoak says. “But it’s not something that you can just say you want to happen. You have to literally do the work together. And that’s going to be true once again as Good Neighbors try to come together and figure out all those alarmists that think they need to patrol a public dock. Against what?”

Lydia Sigo believes that it is not the Tribe’s job to decolonize the minds of their neighbors. She believes that this process must come from within. Although there is movement in this direction, she is not prepared to congratulate the group quite yet.

“Young people like myself didn’t know that they were doing any of that work in the ’90s,” Sigo says. “Us younger generation feel the non-Native Indianolans don’t want us here. That’s all we know, and they show us that through the security guards, the ‘Indianola Residents Only’ sign, and the way their well-off kids are not being integrated into our community. Now they say that they are going to do something about this, but they are at the beginning of their journey of trying to be a good ally to the Tribe again. It would be cool if they make a big effort toward working together in our community. I hope that happens.”

As the next generation takes leadership positions in their communities, there is opportunity for growth.

“I believe in change,” Wandrey says. “I believe in positive kinds of changes that can happen because of the involvement of young parents that we have now. I believe that there are going to be leaders coming up from them. Good things will come. I’ve got a lot of faith.”

Julian White-Davis is a media intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and an undergraduate at Carleton College, where he is studying sociology and political theory. A special thanks to Marilyn Wandrey and Melinda West for their guidance with this article and their deep commitment to their communities. Also thank you to the Suquamish Museum for providing resources and counsel.