NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Meet the Museum Scientist Who Sails the Ocean and Sifts Through Seafood Markets to Identify Fishes

From field sites in Vietnam and the coast of West Africa to her laboratory in Washington, D.C., Kate Bemis applies her knowledge of fish diversity to support sustainable fisheries

Fishes are key to keeping the world fed. Fishes provide nearly seven percent of global protein intake. And with some communities relying on seafood for most of their protein, sustainable fisheries and seafood safety are critical.

Fishes are also the most diverse group of vertebrates — making up more than half of all species with a backbone. With so many fish in the sea, scientists still have much to learn about this incredibly diverse group.

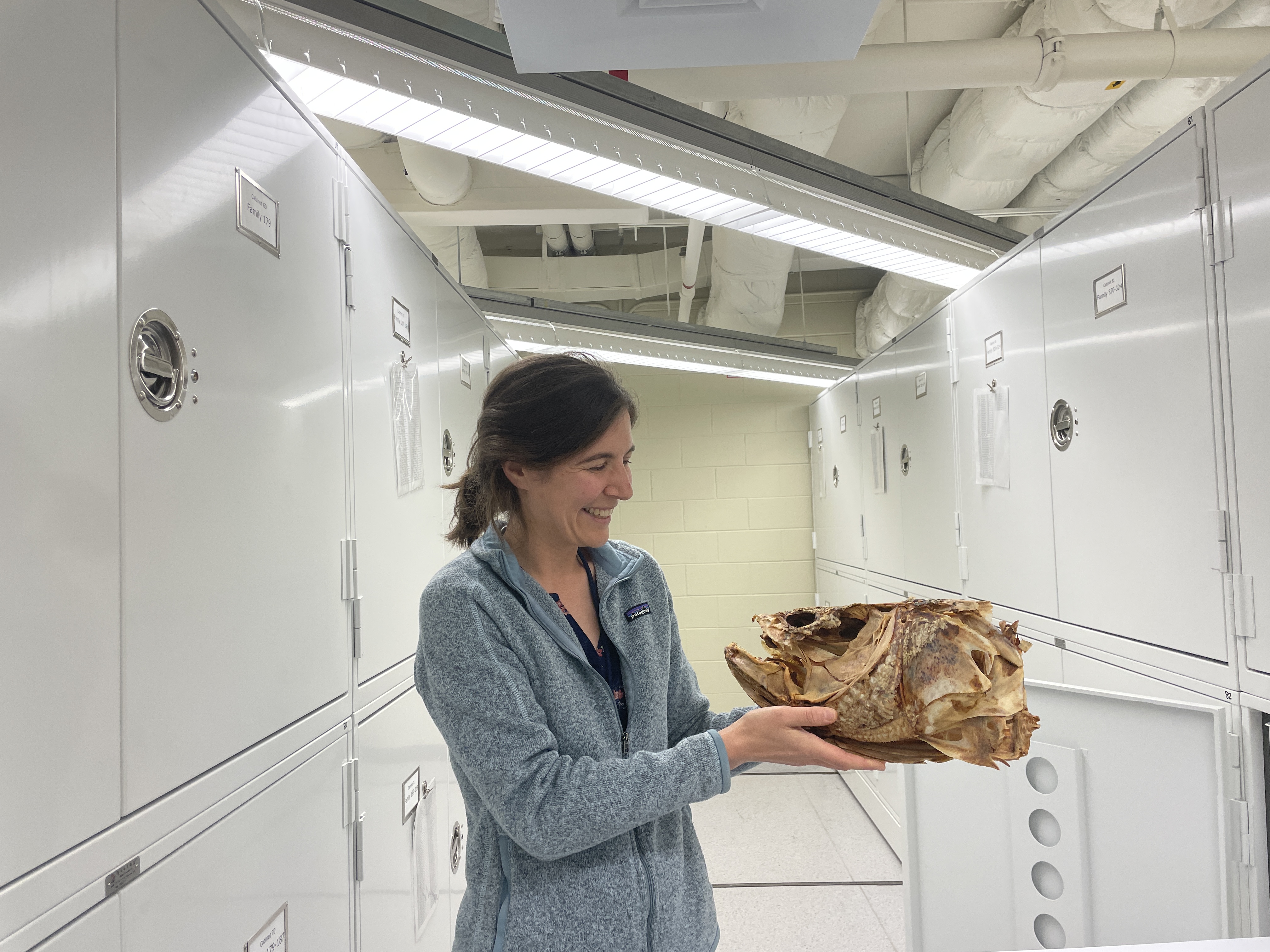

Smithsonian scientist Kate Bemis works at the intersection of sustainable fisheries and fish identification. As a research zoologist in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Systematics Lab and curator of fishes at the National Museum of Natural History, Bemis works in both the Smithsonian collection — the largest fish collection in the world — and aboard research vessels exploring the open ocean.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/30/c7303947-566b-4415-9e13-460208a89a9b/hvcgkaag.jpg)

According to Bemis, who specializes in marine fishes, species identification is the most important part of managing fisheries sustainably. Because each species is different, researchers must understand a particular fish’s biology to make good decisions on how to manage that species. The same goes for food safety, where it is important to properly identify the fishes people are consuming.

Bemis focuses on fishes of the western Atlantic off the US east coast, but has also studied regions of the world where fish diversity is less well understood, such as the Philippines, Vietnam and the Northwest coast of Africa. Above all, however, Bemis studies fishes because she loves learning about all aspects of their biology.

How did you first become interested in studying fishes?

I took a class in high school on sharks and had the chance to see fresh specimens up close. Realizing that we knew very little about their biology was what got me totally hooked. We had a giant frozen Gulper Shark on the table that had been collected by a NOAA Fisheries survey, and yet we had no idea how long they lived for, what the right scientific name was or how many offspring they could produce in a lifetime. Those are just such basic questions, but at the time scientists didn’t know the answers. That was really exciting for me.

What do you like about your job?

I love being in the field, which is something I’ve prioritized in my career. It’s so much fun, and it also helps me understand biodiversity in a different way than if I were just studying the specimens here in the collection. It helps me to see each species as part of a community. I spend a lot of time at sea, particularly on fisheries surveys. When I’m not in the field, I enjoy writing up research and working with students here in the collections.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/13/ff/13ffbb5d-6771-4e5e-83d0-27879198bd20/8jdrh0lq.jpg)

Earlier this year, you were in Vietnam as part of a project funded by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to identify fishes being sold in markets. Why was it important to know which fish were for sale?

Species identification is really the most basic level of seafood safety. We want to know what we’re eating, right?

One of the reasons the FDA project got started is there were filets that were sold in the U.S. that caused people to get sick. When the FDA investigated what they were, they discovered that the fish was incorrectly labeled as a monkfish when it was a pufferfish, which is toxic.

In Vietnam, we worked with colleagues at Nha Trang University to sample fish markets. We picked the best specimens possible and brought them back to the lab. We took color photographs of the fish. Then we take a genetic sample, fix the specimen in formalin, and bring it back to the Smithsonian and archive these samples and their data here at the museum as voucher specimens. These specimens allow us to identify what fishes are being sold in markets and potentially imported to the US.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/7c/727c3566-ce16-4a88-8db1-11f613fa46fd/screenshot_2024-06-06_at_114617am.png)

Why is it important to have both a specimen and a DNA sequence to identify a fish?

We want to have a genetic sample to confirm identifications. Some fish species look similar, and not all seafood, for example a filet, has diagnostic characteristics. By sequencing DNA, we can help inform the identification of seafood that’s being marketed or consumed. Then, the FDA and other agencies interested in seafood safety can compare an unknown fish filet to this information. We use a tool called DNA barcoding, which works by sequencing DNA that is consistent within species, but different between species, to distinguish specimens at the species level. Once we have that sequence data, we can compare across individuals and identify groups that are the same.

But DNA-based identification only works if you have a reference database. So, a lot of my work focuses on building those reference libraries based on voucher specimens, like the ones we collected in Vietnam.

In addition to the specimens and the DNA sequences, I also focus on taking color photographs of specimens and associating them with specimen records. Like a genetic sample, we can use these color photographs to inform identification, and they are a quick tool for improving identification in the field.

The most important thing to take away from museum collections is that when we collect something, we have no idea how it might be used in the future. The more that we can associate with it now — like color photographs, tissue samples, and environmental data — allows those specimens to be the most useful, both for current projects and whenever new technologies or new questions come up in the future that allow us to look at the specimens in new ways.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/b5/b1b5b5be-e8e1-4948-a480-b2cacf5d93d4/kebmgg_2022-033_anthias_nicholsi_usnm_466043_dsc_0492_edited_black_anthias_nicholsi_2_large.jpeg)

Apart from identifying safe seafood, why else is it important to understand the diversity of fish species?

If we’re going to try to conserve our environment, the first step is knowing what we have and understanding each species’ biology. And if we’re going to talk about an animal’s distribution or reproductive biology or age, we need to have a scientific name to be able to tie all that information together.

In some of the places the project has focused — like the Philippines and now Vietnam — fish diversity is really high and there remains so much undescribed biodiversity.

We just published a paper based on the work in the Philippines that identified a new species of fish that was found in a market. And it’s just so cool to me because this was an unknown species and it’s being sold and consumed for food in some parts of the world. These two goals of ensuring seafood safety and understanding biodiversity fit well together.

Speaking about fisheries, you just returned from an exciting research trip to the Eastern Atlantic. Can you tell us what you were studying there?

I just got back from a month-long cruise off the coast of Mauritania, Senegal, and Gambia on the R/V Dr. Fridtjof Nansen, an international research vessel that is a collaboration of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, the Institute of Marine Research in Norway, and Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. The Nansen Programme works with developing countries around the world, including along the west coast of Africa, to collect data that helps countries manage their fisheries sustainably. The Nansen is the only vessel that flies the United Nations Flag, which highlights the vessel’s role as a neutral and international platform for collaborative fishery science.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/93/66935b9b-96c8-41cc-b580-f97f623e0a99/ng6srm8g.jpg)

How can survey data from research vessels like the Nansen help make fisheries more sustainable?

The first step toward sustainable fisheries is to have survey data that lets us know how many fishes are out there. For bottom trawl surveys, we tow a net along the bottom for a standardized time and distance in different areas to collect fishes. We then identify species and collect data on the length and weights of individuals. Species can be hard to tell apart and it’s critical that people are trained in taxonomy so that they can differentiate between species and collect biological data correctly. Data from a single year gives us a snapshot of how fisheries are doing, but the most powerful information comes from having recuring surveys in the same region over time so we can study if species are becoming more or less common or changing their distributions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/43/0f434dcc-d0ba-4e94-9224-aa8cd11057ef/emibvgvg.jpg)

Looking ahead, what are you most excited about for your research?

My immediate hopes are to find ways to strengthen the collaborations that I’ve started to establish. For example, for the Nansen Programme, I’m looking forward to hosting some of the scientists I sailed with to work on the specimens we recently collected that are stored here at the Smithsonian.

I’m excited to get the samples to Smithsonian so we can dig into questions we have about biodiversity. There are just too many good things to work on, and too many good fishes and good people to work with.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Meet a SI-entist: The Smithsonian is so much more than its world-renowned exhibits and artifacts. It is a hub of scientific exploration for hundreds of researchers from around the world. Once a month, we’ll introduce you to a Smithsonian Institution scientist (or SI-entist) and the fascinating work they do behind the scenes at the National Museum of Natural History.

Related Stories

Can Genetics Improve Fisheries Management?

Fishes of the Amazon

Adult Fish Aren’t Truly ‘Protected’ in Many Marine Protected Areas

First global assessment of the sustainability of coral reef fisheries