NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

This Volunteer Week, Get to Know the Smithsonian Volunteer Who Meticulously Curated Thousands of Tiny Crustaceans

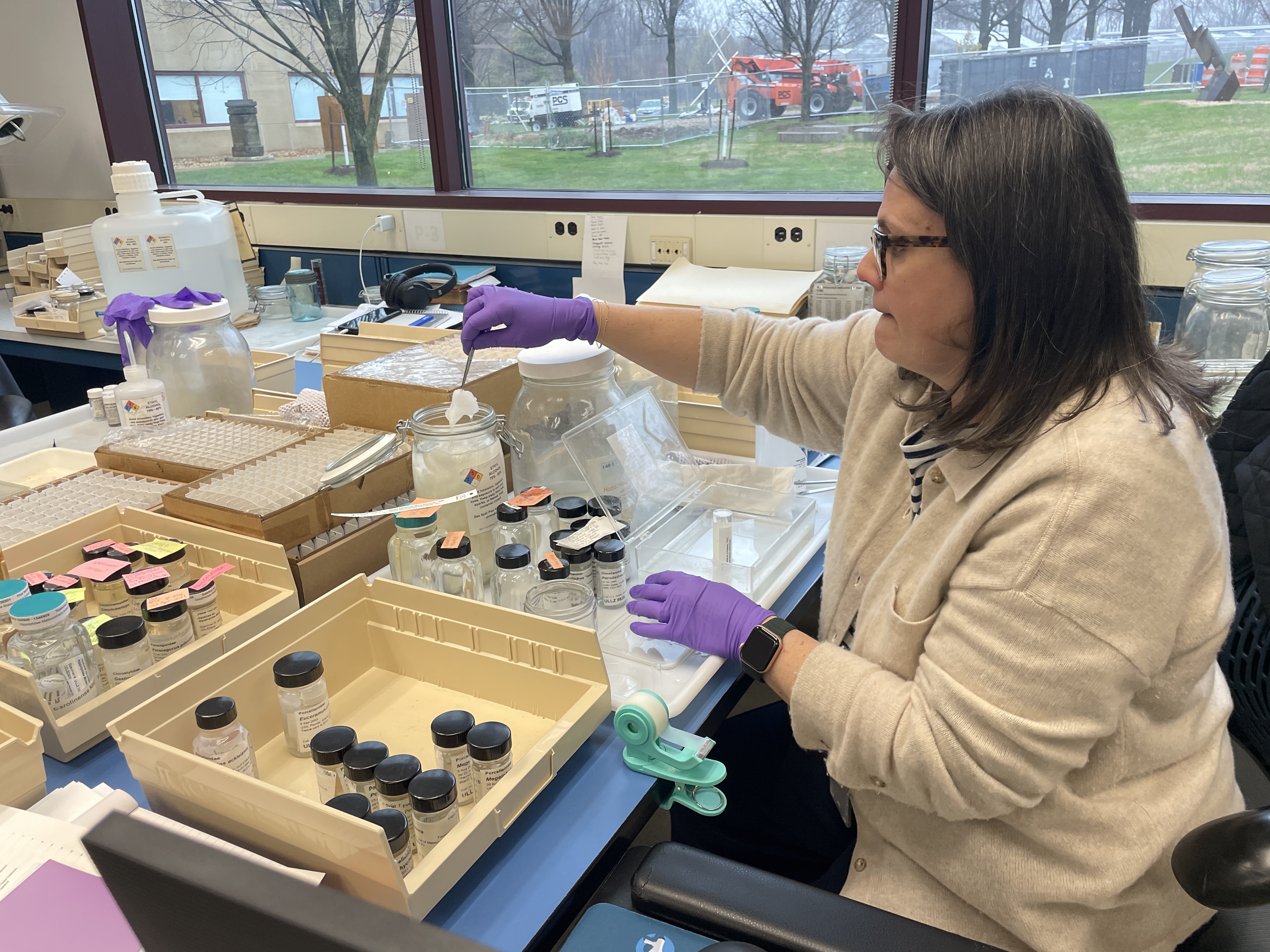

Vial after vial, and label after label, Sofia Barretto Thomas dedicated her time and careful eye to sorting the thousands of amphipods donated by the late cave biologist John R. Holsinger

According to cartoons, every detective needs a trench coat, a spy glass and a brow-obscuring hat. Sofia Barretto Thomas, however, solves mysteries with a keen eye for invertebrate biology. Instead of investigating crimes, Barretto Thomas is diligently organizing a sprawling collection of amphipods, aquatic crustaceans about the size of a macaroni noodle.

For the past three years, Barretto Thomas has volunteered in the Invertebrate Zoology Department of the Museum Support Center of the National Museum of Natural History. She’s spent much of that time carefully disentangling the minute crustaceans, giving each spindly specimen an appropriate label and top-notch housing in museum-grade, ethanol-filled vials. Thomas was recently recognized for this outstanding work by the museum through an award titled “The Holsinger Collection Award.”

John Holsinger, the award's namesake, was a renowned cave biologist who contributed immensely to the field of amphipod identification. His vast amphipod collection, which he dedicated to the Smithsonian upon his death in 2018, contains thousands of specimens representing 300 species, including 59 that were not previously represented in the museum’s Invertebrate Zoology collections. Over 600 of these amphipods are type specimens, which makes them vital for studying and describing these critters. Altogether, Holsinger's specimens hail from 41 states and 40 countries, including Yemen, Mexico and Slovakia.

For Barretto Thomas, following in Holsinger’s footsteps inspired a sense of awe and motivated her to be meticulous when working with the specimens. “You see his life’s work, and you see that you’re the one responsible for these organisms,” Barretto Thomas explained. “I have this respect for what I do and I know the importance of the work for future generations.”

Barretto Thomas’s work cataloguing Holsinger’s amphipods will pay off in the future. Like the rest of the museum’s collections, these specimens are perpetually available for future studies to address a range of questions, many of which scientists aren’t even able to conceptualize yet.

And amphipods are particularly intriguing subjects. According to Baretto Thomas, amphipods are a great indicator of pollution and climate change and might be used in the future to track environmental changes. “We can learn a lot about what’s happening to the environment from these tiny little creatures,” Barretto Thomas said.

But to be research-ready, these specimens require a lot of preparatory work behind the scenes. This is where Barretto Thomas comes in: she takes a large jar or “drum” of amphipods, and separates them by species and when and where they were collected. Using the molecular biology skill set she acquired from her graduate studies in Brazil, Barretto Thomas carefully places an amphipod in a tiny vial, fills it with ethanol and adds cotton to prevent air bubbles. Then, she takes this vial and places it in a second, larger, vial, along with the appropriate label — a process aptly called double-vialing.

Although these steps are delicate and repetitive, Barretto Thomas says she loves doing it. “There’s something very relaxing, almost therapeutic, to curating hundreds of specimens,” Barretto said. “Even though they’re little tiny amphipods, they’re all different species, all different characteristics, and that’s just something that I love to do.”

Barretto Thomas describes herself as a “serial volunteer,” having served on every school and neighborhood committee she could. Of all her volunteer experiences, however, she says the Smithsonian is her favorite because of how it values the volunteers. “Sometimes volunteers are just the people doing work behind the scenes and no one really notices. But here, it’s a different story.”

Barretto Thomas’ coworkers at the Museum Support Center clearly value her. According to her supervisor, Karen Reed, Barretto Thomas stands out because of her dedication. And according to Jocelyn Cooper, a contractor who works across from Sofia in the lab, she is “fantastic to work with.”

While Barretto Thomas’ work is exemplary, she is in good company at the Smithsonian with nearly 4,000 on-site volunteers totaling 230,000 volunteer hours just in 2023. Together with the Smithsonian’s more than 12,000 digital contributors who transcribe museum documents, volunteers are almost as numerous as the intricate amphipods Barretto Thomas carefully sorted.

“There’s something for everyone here,” Barretto Thomas said. “There’s so much work for volunteers, and volunteers are really valued.”

Related Articles

An Appreciation of the Volunteers Who Devote Their Time to the Smithsonian

Interested in Using Museum Collections to Better Understand Freshwater Mussels? There’s Now an App for That

Kidnapper Crustaceans Use Tiny Mollusks as Unwitting Shield

A Huge Shipment of Crustaceans Is Heading North From Louisiana to D.C.