NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

What A 1000-Year-Old Seal Skull Can Say About Climate Change

In a new study published today, scientists at the Smithsonian explain how a seal native to the South Atlantic but found in Indiana likely swam to the middle of North America over 1000 years ago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Group_of_seals_on_a_rocky_beach..jpg)

Once in a while, scientists re-discover an unusual specimen hidden on the shelves of a museum collection. This time, they found a cast of a skull from a Southern elephant seal, Mirounga leonina, which swam upriver to Indiana over 1000 years ago. The cast had been hidden in a drawer of the fossil marine mammals collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History since the 1970s.

“I picked it up and realized it was kind of a mystery. It’s from the middle of the continent, which is the last place you’d ever expect to find an elephant seal,” said Dr. Nick Pyenson, the curator of the collection. He and co-lead authors Maria Zicos and Ana Valenzuela-Toro explained how the seal likely swam to the middle of North America in a new study published today in the scientific journal PeerJ.

“We think this animal somehow swam to the Atlantic from the South Atlantic to the North Atlantic and then somehow entered through the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi River system,” said Valenzuela-Toro, who is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of California Santa Cruz and a Peter Buck Predoctoral Fellow at museum. “That’s half a world away from where these seals are normally found.”

Elephant seals are long distance swimmers, sometimes covering paths of 10,000 miles as they hunt for food in the ocean. This specimen is important because it shows that a seal swam even farther than is considered normal for its species. It is an extreme example of the wide variety of behavior scientists could expect to see in in any given elephant seal.

Casting for clues

Elephant seals have a reputation for randomly ending up in unexpected places. Because seals are mammals, they don’t have gills to filter oxygen from water. This means it’s easier for them to transition from marine water to freshwater. Sometimes a seal will swim up a river and just stay put. The 1000-year-old elephant seal suggests that this fluke behavior has been happening for a long time.

“When you look at organisms, you realize they have a very broad way of doing things. Marine mammals appear to be able to get really far from their main geographic areas,” said Pyenson. “And species that can disperse across far distances are better buffered against sudden changes to their local environment.”

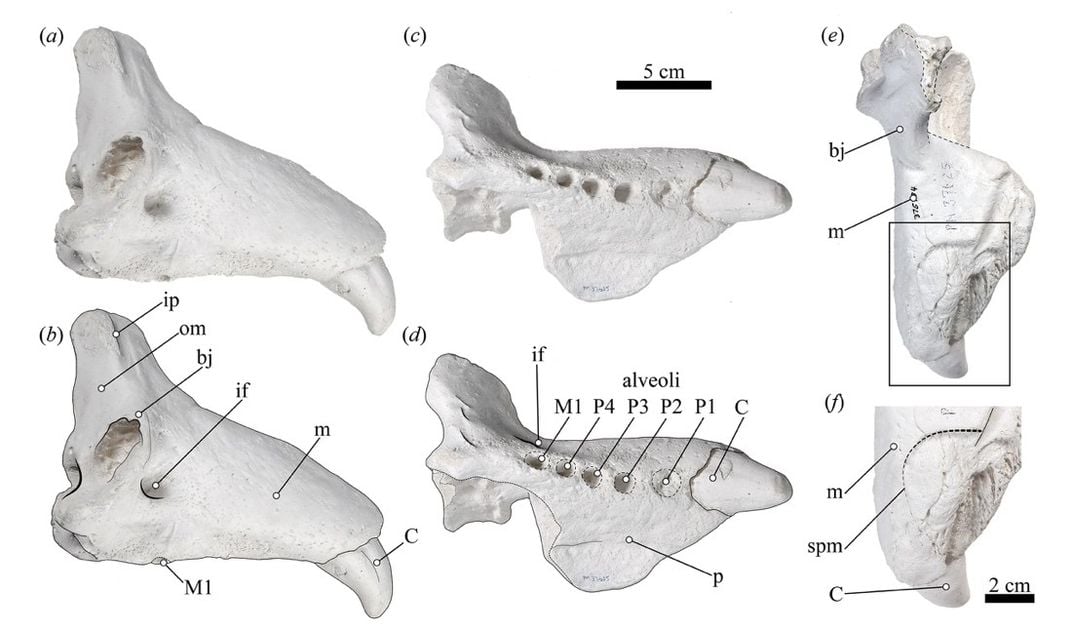

To learn more about the specimen, Valenzuela-Toro, Zicos and Pyenson had to rely solely on morphology — the study of an animal’s physical characteristics to determine its species. They did so by comparing the cast of the skull to more recent specimens in the marine mammals collection.

“We went to the collection and started taking out elephant seal skulls from drawers. That’s where it clicked for me that this was the cast of a skull from an elephant seal,” said co-author Zicos, who is currently a Ph.D. student at Queen Mary University of London.

By comparing the cast with other specimens from different species, they determined that it represented a male Southern elephant seal. It also had some marks that suggest it may have been butchered by Indigenous people after being found. It seemed unlikely that a complete skull was traded from South America to North America, according to the team. Instead, they argued that the seal likely strayed off its annual migration pattern and swam to Indiana by accident. That explanation aligned with behaviors other scientists have observed seals doing today.

The past is about the future

Both Southern and Northern elephant seals suffered from extreme hunting in the 1800s. Today, they face another obstacle: climate change. But by learning more about the species’ range of behavior in the past, scientists can better predict the many ways they could react to global challenges now.

“Understanding the range of what an animal species is, and historically was, capable of is helpful. Sometimes what we think it can do is just a fragment of its actual possibilities,” said Zicos.

This lost elephant seal symbolizes what can happen when an animal’s actions are on the extreme side of its species’ behavioral range. If some seals were already likely to swim very far upriver and get lost during times with less environmental stress, who knows how many of them might do so under extreme environmental upheaval.

Collections record species behavior

There are countless objects in the museum’s fossil marine mammals collection that represent a wide range of past animal behavior, distribution and anatomy. The Smithsonian’s collection of marine mammals currently includes over 15,000 fossils and casts of specimens from 50 million years ago to present day.

“This specimen is very interesting not only because it shows us particular characteristics of past elephant seals but because it also demonstrates the value of recording, maintaining and improving our museum collections,” said Valenzuela-Toro.

Studying the constantly growing collection can help researchers know more about what might happen in the future.

“Our shared future with other species is about what just happened in a very tangible way and there’s nothing more tangible than having a museum record,” said Pyenson.

Related Stories:

10 Popular Scientific Discoveries from 2019

Saving This Rare Whale Skeleton was a Dirty Job

Here's How Scientists Reconstruct Earth's Past Climates