NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

The Italian Campaign, the Lord’s Prayer in Cherokee, and U.S. Army Sergeant Woodrow Wilson Roach

Sgt. Woodrow Wilson Roach (Cherokee, 1912–1984) served with the Fifth Army during the Italian Campaign, the longest continuous combat and some of the fiercest fighting of World War II. Here, his granddaughter tells the museum about his life and the Cherokee language prayer card he carried as a soldier in Europe, then as a combat engineer in the Philippines. We’re especially proud to share Sgt. Roach’s story this weekend, during the groundbreaking for the National Native Veterans Memorial. The memorial—to be dedicated on November 11, 2020, on the grounds of the museum on the National Mall—honors the Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native men and women who have served in the U.S. Armed Forces since the country was founded.

:focal(804x224:805x225)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Woodrow_Roach_WWII_1500_x_900.png)

Family information for this story is provided by Della Boyer.

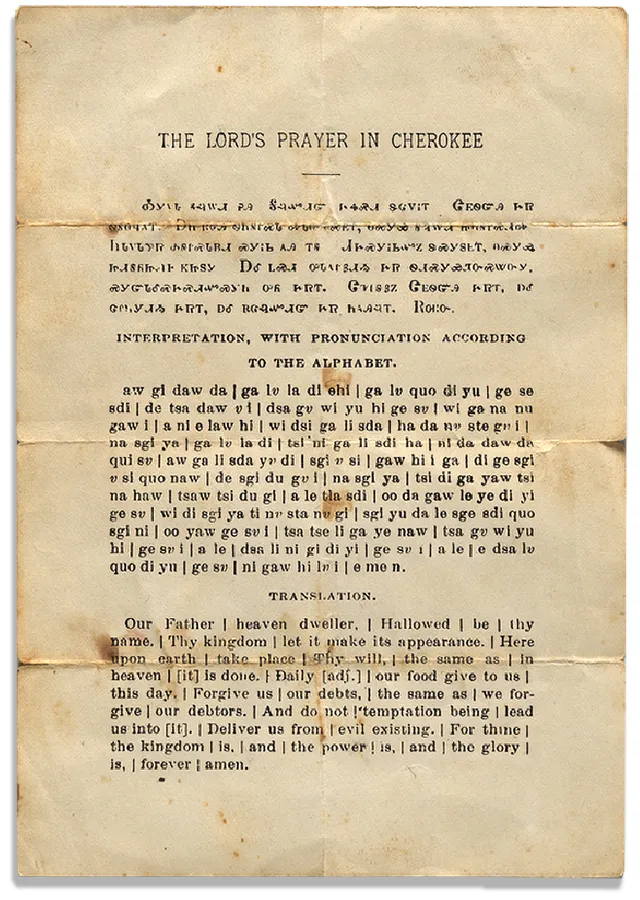

One of the most poignant donations the National Museum of the American Indian has ever received is a Cherokee prayer card carried during World War II by U.S. Army Sergeant Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Roach (Cherokee, 1912–1984). The Lord’s Prayer is printed three times on the carefully preserved prayer card—in the Cherokee syllabary (characters representing syllables), Cherokee phonetics, and English. The prayer card was given to the museum in 2014 by Roach’s granddaughter Della Boyer. Following her grandmother’s wishes, Ms. Boyer made the donation to honor her grandfather’s memory, “so that other people will know of the sacrifice he made for his country.” Ms. Boyer explained that she also made the gift because she knows there are many veterans and families who can relate to her grandfather’s carrying his prayer card with him during the war. “Many soldiers,” she said, “needed that one thing that gave them comfort and security during very trying times.”

According to Ms. Boyer, her grandfather served both in the Fifth Army during the Italian campaign and in an engineering battalion in the Philippines campaign. Trained in amphibious assault, the Fifth Army breached the Italian mainland on September 9, 1943. Tens of thousands of American infantry soldiers and allied troops lost their lives advancing through towns whose names will never be forgotten—Salerno, Cassino, Anzio—as well as across countless valleys, rugged mountains, and mountain passes. Famously, the Fifth Army fought continuously against fierce enemy resistance for 602 days. In 1944 the field army was charged with liberating the Po Valley and freeing all of northern Italy from German control. Woody Roach arrived in the war-torn, bombed-out city of Naples in the summer of that year. The hard-won campaign resulted in the surrender of German forces, which became effective on May 2, 1945.

Roach believed, as does his family, that his prayer card allowed him to return home safely. Trained at Fort Chaffee near Fort Smith, Arkansas, Roach not only saw heavy combat during the Italian campaign but, upon at least one occasion, put his life at grave risk to save his fellow soldiers. He and his unit were under a barrage of enemy gunfire and a road-grader blocked their path. Roach crawled to it and managed to drive the construction machinery out of the American soldiers’ way. After his service in Italy, Roach was sent to the Philippines. The Imperial Japanese Army had attacked that country nine hours after the raid on Pearl Harbor. In 1945 Japanese forces still occupied many Philippine islands. Roach, who had knowledge of mechanics, was transferred to an engineering battalion to help build bridges. U.S. Army combat engineers played a crucial role in the supporting front line American and Filipino troops fighting for the liberation of the Philippines.

Roach was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma. His father, Thomas P. Roach, was an Indian Service police officer, and his mother, Annie, was a teacher. According to Ms. Boyer, her grandfather had a hard life. He grew up in boarding schools. He ran away from Chilocco Indian School in north-central Oklahoma when he was first brought there, eventually earning a boxing scholarship while at the school. Roach graduated from Bacone College in Muskogee during the Depression and the severe drought and dust storms of the 1930s.

It was not an easy time, but Roach came from a family that had survived much adversity. In the late 1830s, his grandfather was one of thousands of Cherokee people forced from their tribal homelands east of the Mississippi River by the U.S. government and removed to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), beyond the settled borders of the United States at that time.

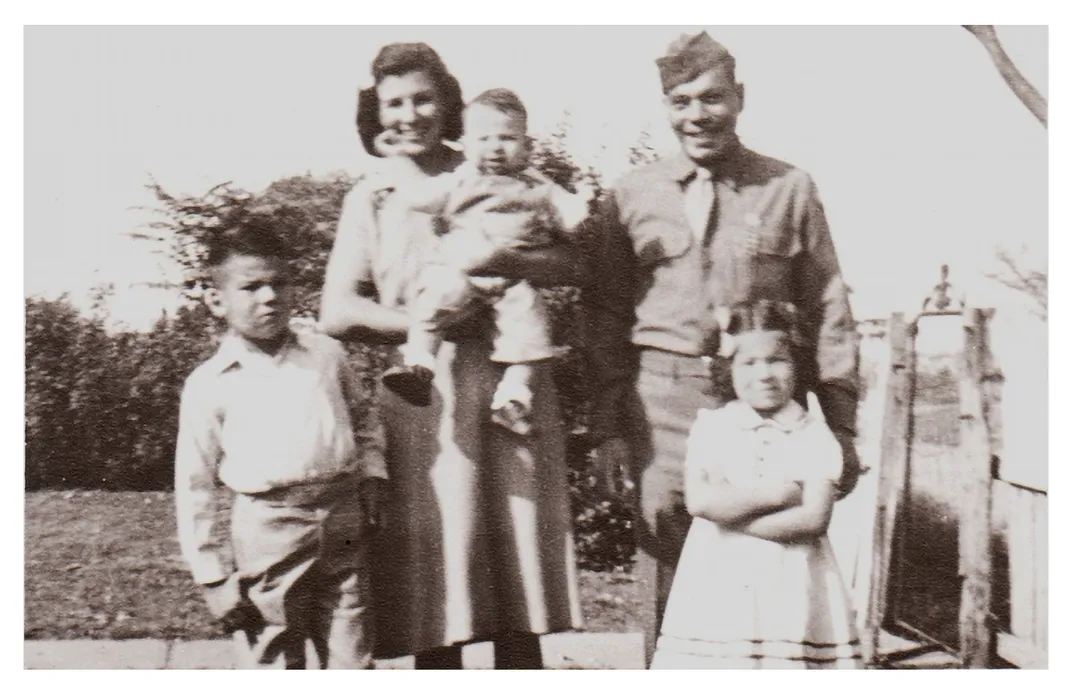

Roach was 32 years old and married with three children under the age of five when he joined the U.S. Army. He did not know if he would ever see his children again. Ms. Boyer notes that, like a lot of women during the war, her grandmother Della took care of the family on her own. The Roaches had two more children after the war. Their son Kenneth (d. 2017) grew up to be a teacher. Their daughter Pat also retired after a career teaching. Both Kenneth and Pat had master’s degrees. Shirley is an attorney and CPA. Paul (d. 2017) was an attorney with a successful career in business. Ed (d. 2014) was a Marine who fought in Vietnam.

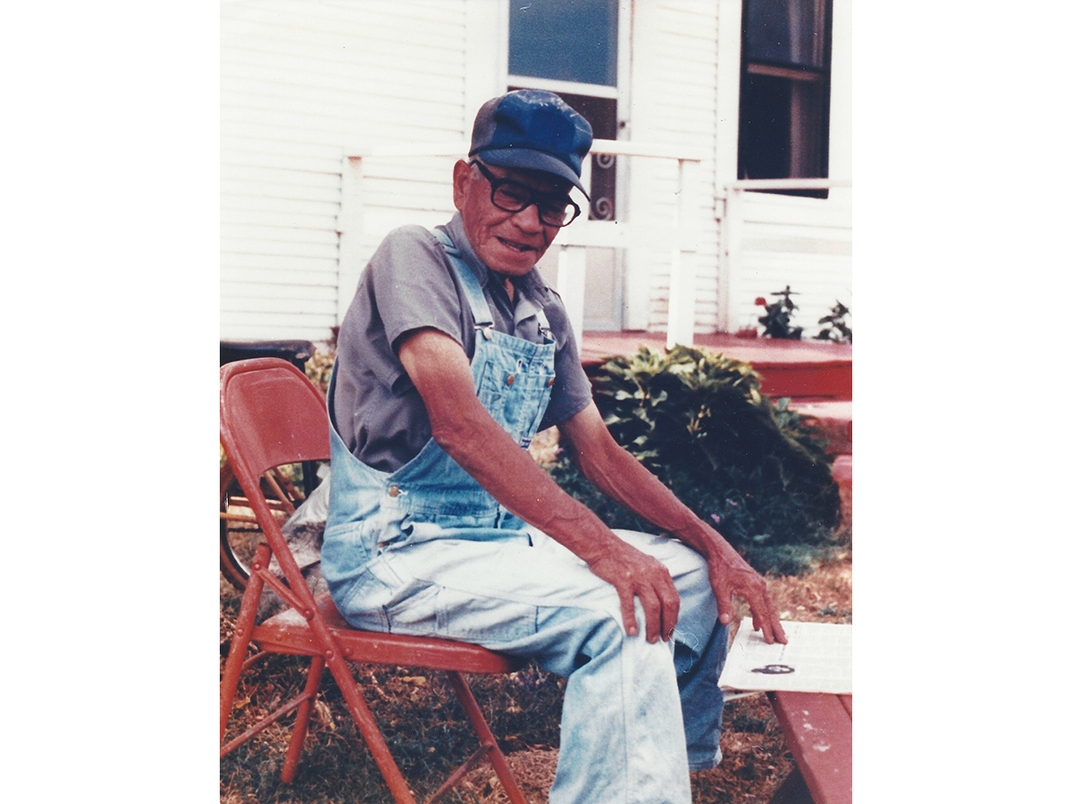

After World War II, Roach worked for many years as an engineer for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). He built roads and bridges in Florida and Mississippi on Seminole and Choctaw reservations. This was during the period of Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination in the South. Once, at a movie theater in Philadelphia, Mississippi, Roach was told that he could not sit with his wife, who was white, in the whites-only section of the theater. Outraged, he called the town’s mayor, who was a friend. Roach watched the movie that evening sitting alongside his wife. When he retired from the BIA, Roach taught industrial arts, or shop class—machine safety, small engine repair, car maintenance, etc.—at the Sequoya Indian School in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Throughout his life he also worked as a farmer and operated a gas station.

Ms. Boyer describes her grandfather as a humble man who did not like to call attention to himself, but also as very smart and articulate. She says that he rose through the military ranks quickly and that his former students describe him as tough but good-hearted, and a positive influence on their lives. Although never officially trained or recruited as code talkers, Roach and a fellow soldier relayed military information in fluent Cherokee. Years later they would chuckle together about “really outsmarting those Germans.” At his funeral, his friend told Della’s grandmother that he was one of the soldiers whose life Roach had saved. After her grandfather’s death, Ms. Boyer also learned from her grandmother that Roach always cherished his friendship with an “old Indian man” named Yellow Eyes who fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, a stunning defeat for the U.S. Army in 1876 and a victory for the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies.

Like so many other veterans of his generation, Roach was a man who shouldered his responsibilities with an unwavering sense of purpose and a strong belief in who and what he was. His prayer card, safeguarded throughout his life, is a reminder not only of his faith and service to his country, but of the United States’ complex and deeply entangled history with American Indians. Native American WWII U.S. Army veteran, Woodrow Wilson Roach survived colon cancer in 1973 but succumbed to lung cancer in 1984. He was buried with a military funeral.

Della Boyer is one of Woodrow Wilson Roach’s 15 grandchildren. Ms. Boyer, a therapist and mother of two, lives outside Denton, Texas.