NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Marking the 400th Anniversary of Pocahontas’s Death

The broad strokes of Pocahontas’s biography are well known—unusually so for a 17th-century Indigenous woman. Yet her life has long been shrouded by misunderstandings and misinformation, and by the seemingly inexhaustible output of kitsch representations of her supposed likeness. The conference “Pocahontas and After,” organized by the University of London and the British Library, sought a deeper understanding of Pocahontas’s life and the lasting impact of the clash of empires that took place in the heart of the Powhatan Confederacy during the 17th-century.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Pocahontas__Elizabeth_I_1500x860.png)

March 21, 2017, was the 400th anniversary of Pocahontas’s death. She was about 22 years old when she died, and both her life and death are being commemorated in London. One key event—a three-day conference titled "Pocahontas and after: Historical culture and transatlantic encounters, 1617–2017"—was organized by the University of London School of Advanced Studies’ Institute for Historical Research and the British Library, and took place March 16 through 18. Pocahontas spent the last nine months of her life in London and was known there as Lady Rebecca.

Born Amonute, Pocahontas was the daughter of the leader of the powerful Powhatan Confederacy. The confederacy dominated the coastal mid-Atlantic region when, in 1607, English colonists established James Fort, a for-profit colony, along the Chesapeake Bay. Pocahontas, a child at the time, often accompanied her father’s men to the fort, signaling that their mission was peaceful. Amazingly or not, the English arrived poorly equipped, lacked provisions, and were almost entirely dependent on the Powhatan for food. Over the years, Pocahontas was among those who brought food to the fort.

Relations between the English and Powhatan, however, were always fraught. And in 1613 Pocahontas, then about 18 years old, was abducted by the English and held hostage for more than a year. The Christian theologian Alexander Whitaker eagerly began to instruct Pocahontas, already learning to speak English, in the tenets of Anglicanism. While captive, Pocahontas met the colonist John Rolfe, who—according to various English accounts, including his own—fell in love with her. Pocahontas agreed to marry Rolfe and, shortly before her marriage, received a Christian baptism. It was Rolfe who developed the strain of tobacco that would make the colony prosperous, enrich its investors and Britain, and eventually lead to the collapse of the Powhatan Confederacy.

In 1616 Pocahontas traveled to London with Rolfe and their infant son, Thomas. Her trip was sponsored by the James Fort investors. Famously, Pocahontas, accompanied by an entourage of high-standing Powhatan, was feted throughout London. She was twice received in the Court of King James—to be presented to the king and to attend a Twelfth Night masque. Pocahontas never returned home. She died at outset of her return voyage and was buried in Gravesend, an ancient town on the banks of the Thames Estuary.

Although the broad strokes of Pocahontas’s biography are well known—unusual for a 17th-century Indigenous woman—her life has long been shrouded by misunderstandings and misinformation, and by the seemingly inexhaustible output of kitsch representations of her supposed likeness. Within a few years after her death, the Theodore De Bry family’s 13-volume publication America, translated into several languages, provided the book-reading public beyond London with what they considered to be their first real and comprehensive glimpse of the New World’s indigenous peoples, including Pocahontas. Four hundred years later, her name has become familiar to children worldwide through Walt Disney Picture’s 1995 animated film Pocahontas, strong on memorable melodies, although weak on historical and cultural accuracy.

It is known that, while she was in London, Pocahontas met Captain John Smith, at one time president of the council for the James Fort colony, and expressed her displeasure with him and those of his countrymen who “lie much.” Those familiar with the facts of Pocahontas’s life, however, are only too aware that her thoughts surrounding the events that dramatically impacted her and her people are largely unrecorded by history. "Pocahontas and after" brought together approximately 50 international scholars—including several Native scholars—from a variety of disciplines to reflect upon what is actually known of Pocahontas’s life and times, on both sides of the Atlantic, and on the ways in which her life has been construed and misconstrued over the last four centuries.

To give but a suggestion of their scope, conference papers ranged in topic from American Indian marriage practices for establishing and maintaining political alliances, to the lives of two English boys allowed to live among the Powhatan in order to learn Algonquian, the biblical significance of the name Rebecca, the startling number of American Indians who voyaged to London in the early 17th century, the James Fort investors’ motivations for bringing Pocahontas to London, and the political meanings embedded in the three representations of Pocahontas on view in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Among those taking part was Chief Robert Gray of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe. The Pamunkey people descend from the Powhatan. On the last day of the conference, Chief Gray spoke at the British Library on the history of the Pamunkey. His paper was titled “Pamunkey Civil Rights and the Legacy of Pocahontas.” In the Q&A that followed his presentation, and as a surprise to some, he further addressed the issue of why many Pamunkey people have ambivalent feelings towards Pocahontas. He spoke candidly about Pamunkeys’ general displeasure with Pocahontas’s story having been appropriated by non-tribal members. He shared his people's priority and overriding desire to make known the history of such Pamunkey as Chief George Major Cook (1860–1930), who fought to defend Pamunkey rights during the Jim Crow era, when racial segregation was written into the law, and the period surrounding the 1924 Racial Integrity Act, when the state of Virginia forced all citizens to have their race, “colored” or “white,” registered at birth and forbade interracial marriage. These laws essentially sought to legislate Pamunkeys and other Virginian Indian tribes out of existence. Gray was frank in explaining how Pamunkeys long invoked the name Pocahontas to assert their sovereignty, to no avail, while politically influential Virginians successfully invoked their descent from Pocahontas to have an exemption written into the Racial Integrity Act that classified them as “white.”

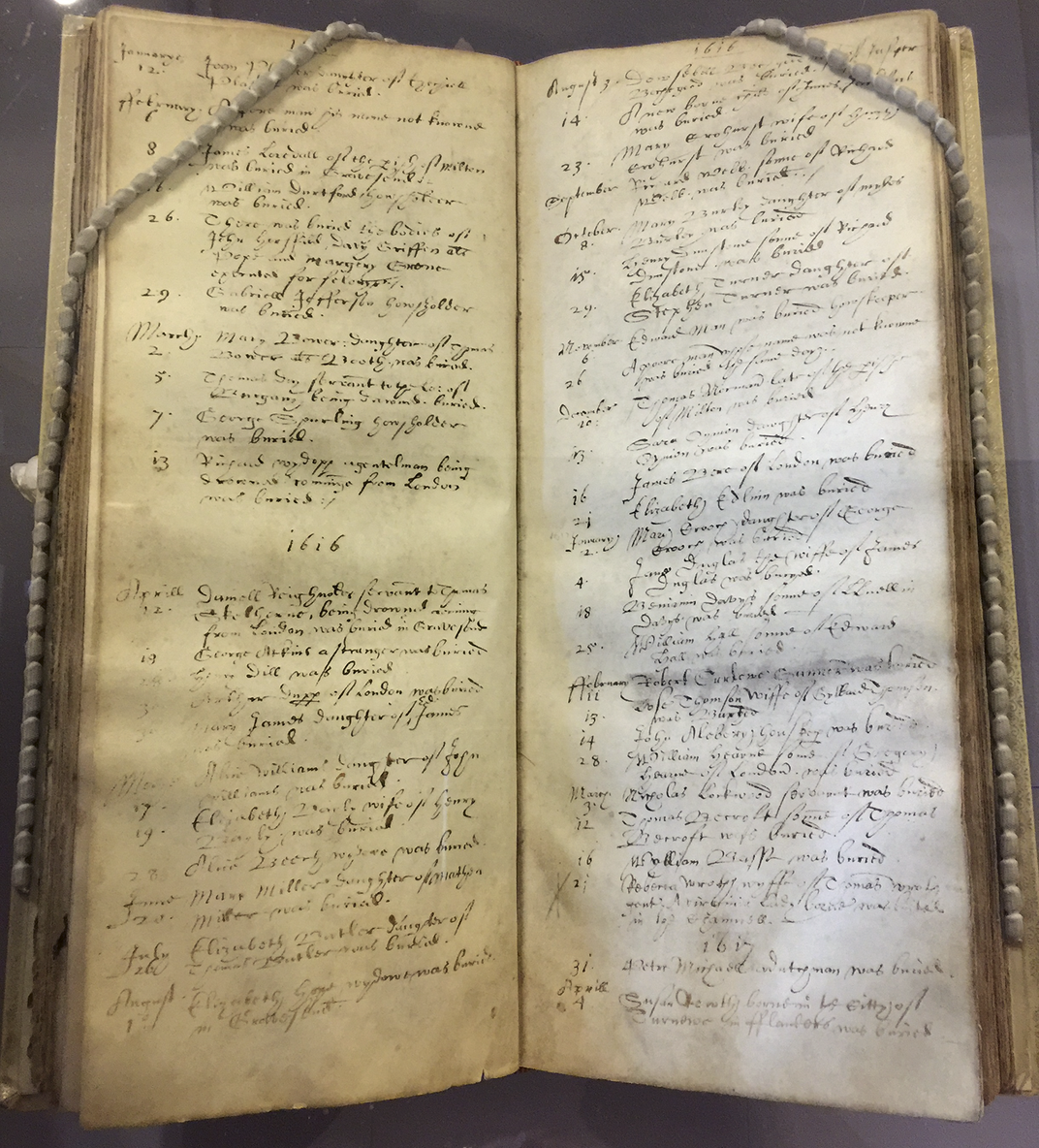

Pocahontas continues to hold a singular and singularly contested place in history. "Pocahontas and after" succeeded in conveying to all present that the shroud covering Pocahontas’s life needs to be lifted. For the anniversary week of Pocahontas’s death, and to commemorate her life, the rector of St. George’s Church displayed the church registry that dates back to 1597 and records her burial. In keeping with the Christian and English tradition of acknowledging the death of a person of high social standing, Pocahontas was buried in St. George’s chancel. The registry is poignant evidence of the life of a young Powhatan woman who lived and died in the maelstrom of the British–Powhatan encounter in the early 17th century.

It seems likely that we will never fully know what Pocahontas thought of her abduction, instruction in the tenets of Anglicanism, marriage to John Rolfe, and experiences in London. But an understanding can be built around her life based, not on fabrications, but on Pamunkey knowledge and scholarly research that cuts through 400 years of appropriations, misinformation, and romanticism. There emerged at the conference a sense that a picture of early 17th century life in the mid-Atlantic region can be brought to light that gives greater insight into the clash of empires that occurred in the heart of the Powhatan Confederacy and that illuminates the historic processes and legacies of European colonization, and Native strategies for confronting them.

Notes

Based on English sources, Pocahontas’s birth date is estimated to be 1595.

A collection of portraits, Baziliologia: A Booke of Kings (1618) was republished with slightly varying titles. For a history of the various editions, see H. C. Levis’s discussion of them in the Grolier Club’s 1913 reproduction of the 1618 edition of Baziliologia: A Booke of Kings, Notes on a Rare Series of Engraved Royal Portraits From William the Conqueror to James I. The van de Passe engraving of Pocahontas and engravings of other prominent notables were added to a later edition. Few of any editions survive, and all that do appear to vary in content. An “Expanded Baziliologia” held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford includes the Pocahontas engraved portrait.

The text in the oval frame encircling Pocahontas's portrait reads, "MATOAKA AĽS REBECCA FILIA POTENTISS: PRINC: POWHATANI IMP: VIRGINIÆ." The text below her portrait reads: "Matoaks als Rebecka daughter to the mighty Prince Powhâtan Emperour of Attanoughkomouck als virginia converted and baptized in the Christian faith, and wife to the wor.ff Mr. Joh Rolfe." Pocahontas was a nickname given to Amonute by her father. Matoaka was her private name, which she revealed to the English colonists. Rebecca was the Christian name she received when she was baptized. Lady is an English title accorded noblewomen. Pocahontas was recognized as the daughter of an emperor of Virginia.

Pocahontas entered European history books before she even sailed to London. In 1614, two years before her transatlantic voyage, Ralph Hamor, one of the original James Fort colonists, published A True Discourse of the Present State of Virginia. In it he described her abduction. In 1619, the Theodore de Bry family published volume 10 of America and not only recounted the abduction story, but illustrated it with an engraving. In 1624, Jamestown colonist John Smith published his Generall Historie of Virginia, New England & the Summer Isles and it included, for the first time, his dramatic account of his capture and imminent death at the hands of Powhatan and his men. He described how his life—and by extension, the colony—was saved by Pocahontas. The Simon van de Passe Pocahontas portrait was published in Smith’s Generall Historie of Virginia, as well as in certain editions of Baziliologia: A Booke of Kings.

For Pocahontas's London meeting with John Smith, see Camilla Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma (2004), pages 154–156.