Why Poor School Reports Didn’t Stop One Artist from Spelling Success

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_pachwalt_40522_SIV_crop.jpg)

Packing my two boys off to school in September, after a lazy (for them at least) ten week summer break, has left me feeling rather like I’ve been shot from a cannon. Predictably each morning finds me frantically exhorting my nine-year-old son to put down his Calvin and Hobbes book, or the latest Lego micro-spaceship he’s designed, or whatever piece of plastic junk has caught his attention this week, and put on his shoes so we can get to school already! Once again I’m fretting about how to help him stay focused and engaged as the ever more pressing weight of school work competes in his fourth grade brain with more appealing childhood distractions. Not that I’m worried about him. He’s a curious, happy and empathetic kid, and I don’t have a problem getting him to read or play on his own—I just have a problem getting him to do anything else. So when I came across these school letters in the Walter Pach papers, describing the twelve-year-old Pach, I recognized a familiar scenario.

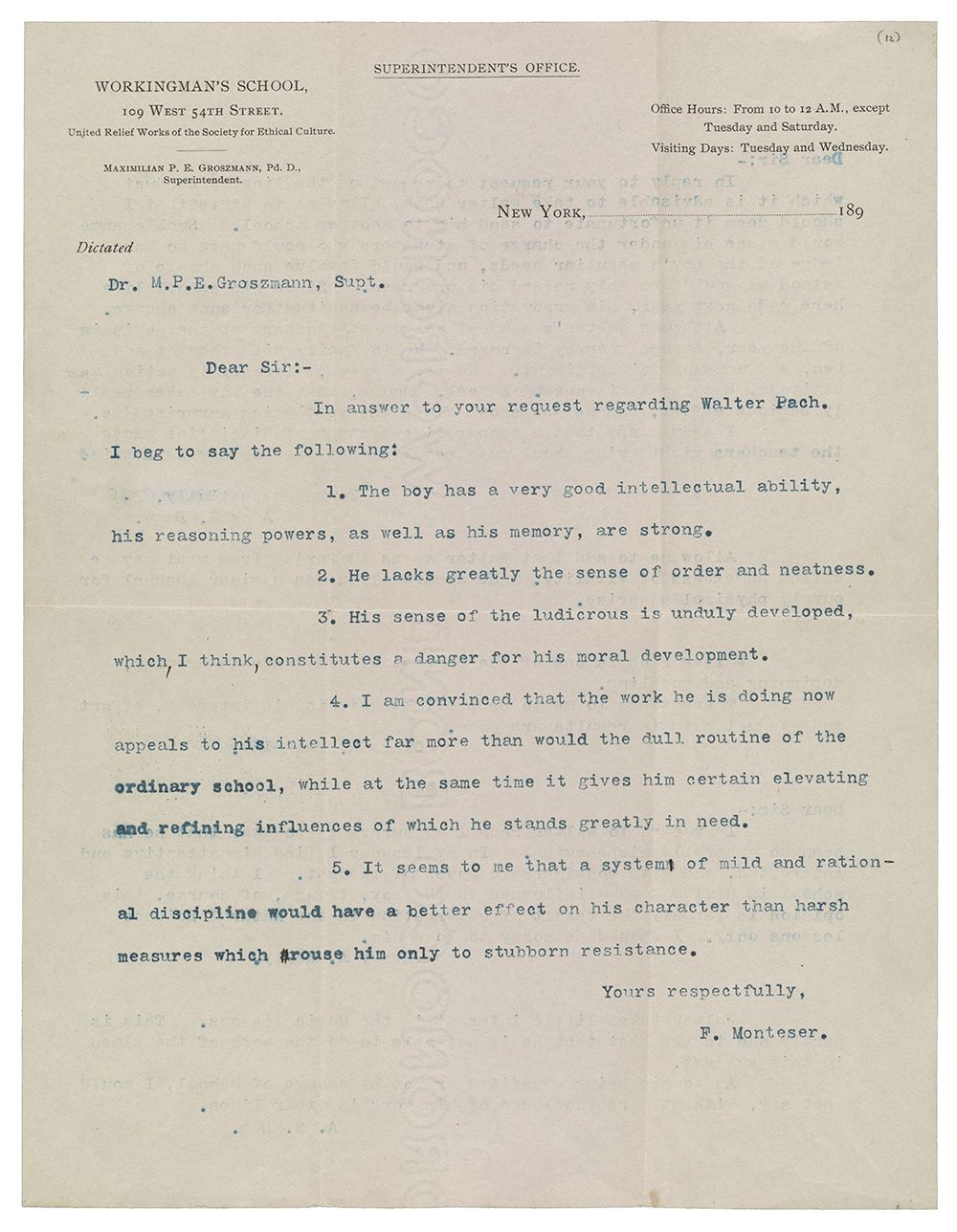

Walter Pach, influential artist, critic, writer, and art consultant who helped bring the avant-garde to America in the landmark Armory show of 1913, was attending the private Workingman’s School in New York City in 1895. Soon to be renamed the Ethical Culture School, it was renowned for a commitment to social justice, racial equality and intellectual freedom. In 1895 Pach would have been in seventh grade and, by all accounts, he was struggling.

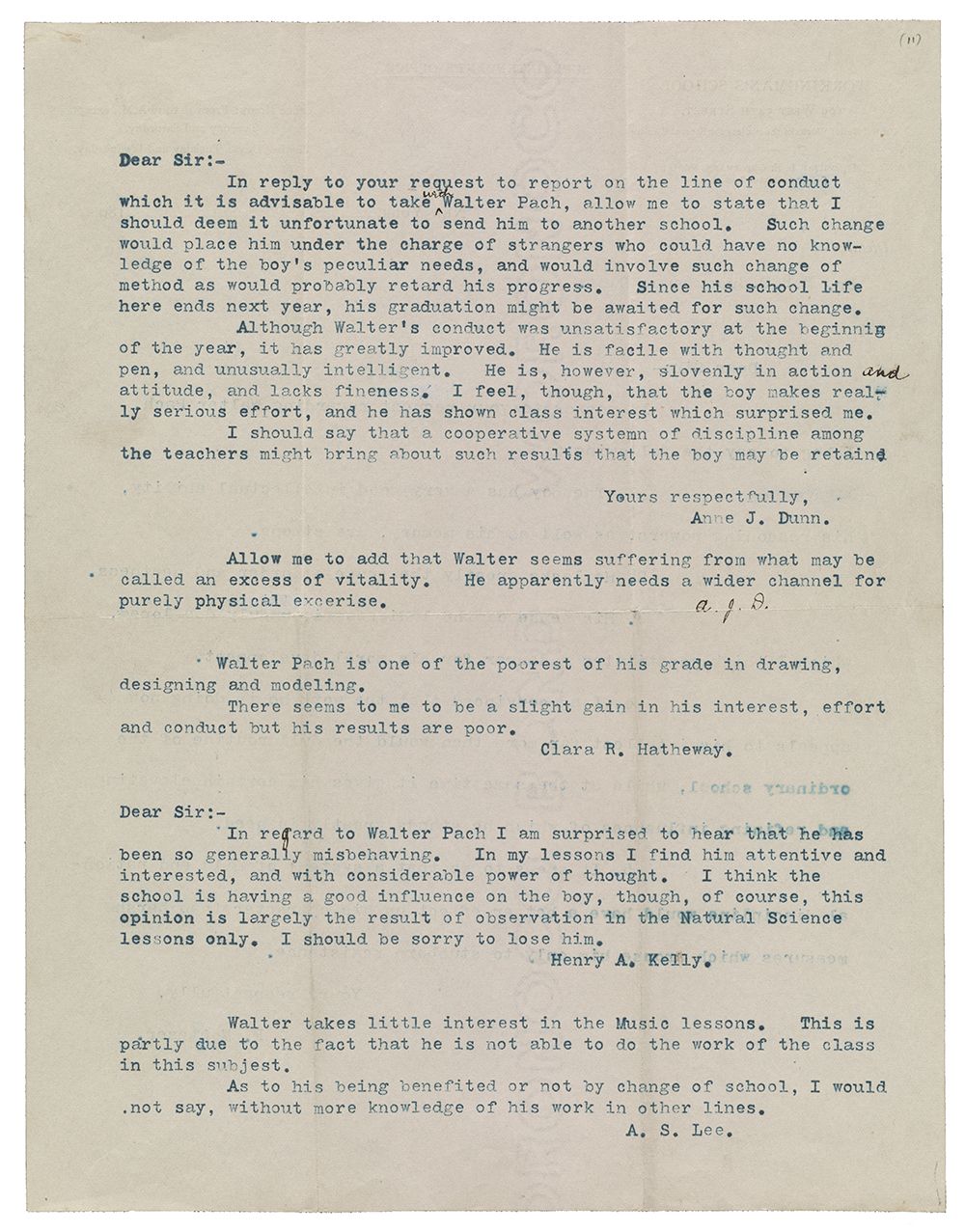

Following a meeting with his father, Pach’s teachers had been asked to report on the child’s progress and weigh in on the possibility of his suspension and transfer to the public school system. Walter, one said, suffered from “an excess of vitality.” The young Pach questioned why he should be made to do mechanical drawing when he hated it, took “little interest in music,” and was “one of the poorest of his grade in drawing, designing and modeling.” He lacked “greatly” the qualities of “order and neatness” and had a “sense of the ludicrous” so “unduly developed” that it constituted “a danger for his moral development.”

Despite a rocky beginning in seventh grade, Pach’s teachers nevertheless noted his “very good intellectual ability” and had discerned some improvement as the year progressed. They saw a boy who was “facile with thought and pen and unusually intelligent,” despite being “slovenly in action and attitude,” and most felt that he would benefit from remaining at the school and receiving the special attention he needed to overcome his “faults.” There was a general consensus that the harsh disciplinary measures likely to be meted out in public school would be counter-productive for the feisty Pach, who was prone to “stubborn resistance” when disciplined. “The moment I censure him,” remarked one teacher, “he gets all excited and he is not the master of himself.” Now that sounds familiar.

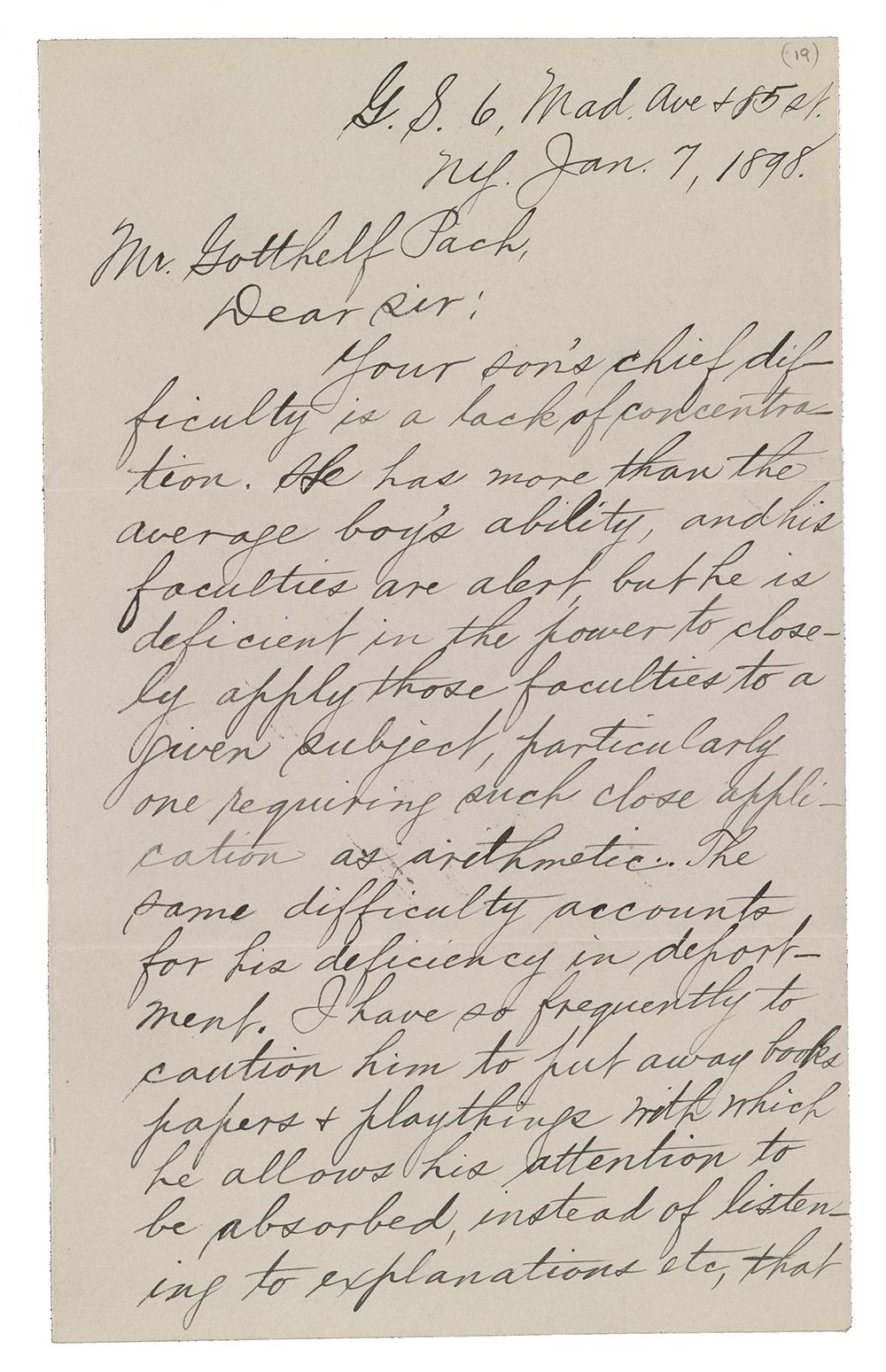

Nevertheless, Pach was transferred to Public School 6 on the Upper West Side at some point during the next few years. In 1898, arithmetic teacher Magnus Gross lamented in a letter to Pach’s father that he had “so frequently to caution him to put away books, papers and playthings with which he allows his attention to be absorbed,” that he recommended “that all reading (except upon subjects connected with his studies) be forbidden him....and that all distractions of any nature (except a due amount of physical exercise) be removed from him.” Poor Walter.

Not that I’m comparing the potential of my offspring to that of a renowned art-world figure, but it’s reassuring to know that a dearth of interest in arithmetic and a penchant for (gasp!) books and playthings during childhood does not necessarily doom a boy to failure. The young Pach clearly had a mind of his own, and while he appears to have struggled, at least for a time, to apply it effectively within the constraints of a grade school education, his intellect was eager and quick and hinted at a fascinating life to come: Pach befriended and corresponded with some of the major European, American and Mexican artists and art-world figures of the first half of the twentieth century. He helped to form the legendary collections of Walter Arensberg and John Quinn. Fluent in French, German and Spanish he was able to effectively translate avant-garde ideas emerging from Europe for an American audience, and he wrote extensively on art, artists, and museums. On top of all that he was an artist in his own right. Not bad for the poorest in his grade.

A version of this post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.