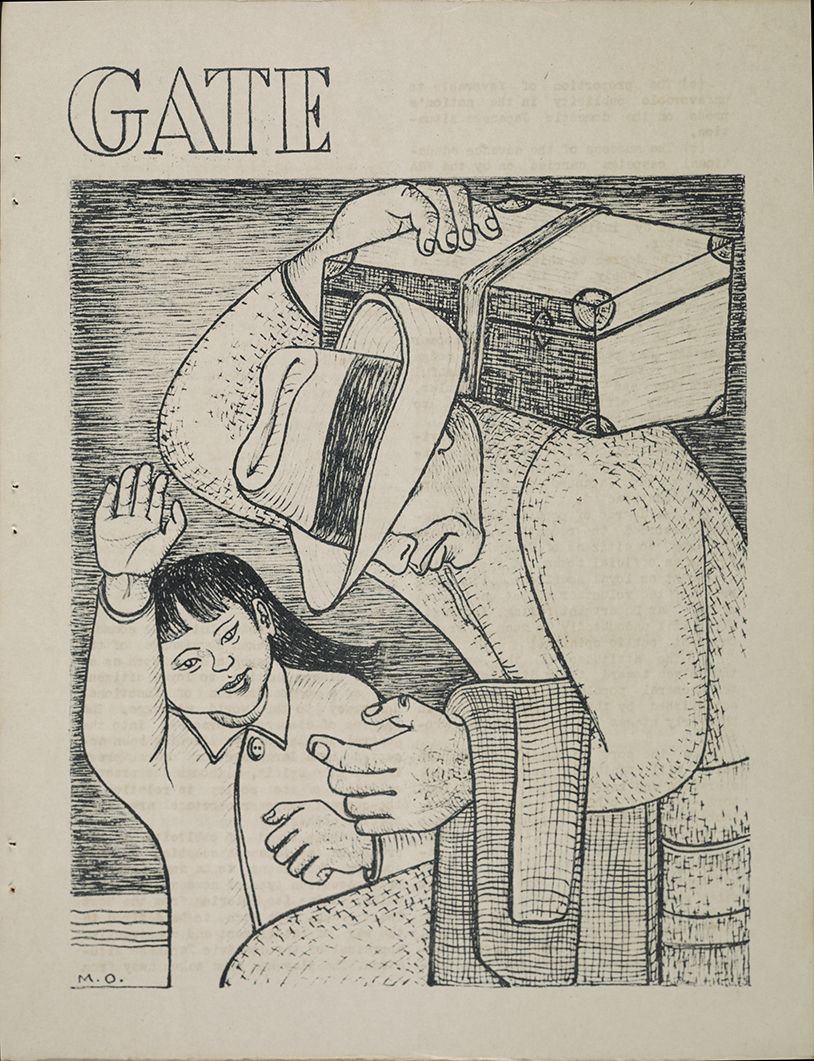

Miné Okubo, Number 13660

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_mccoesth_58623_detail_SIV.jpg)

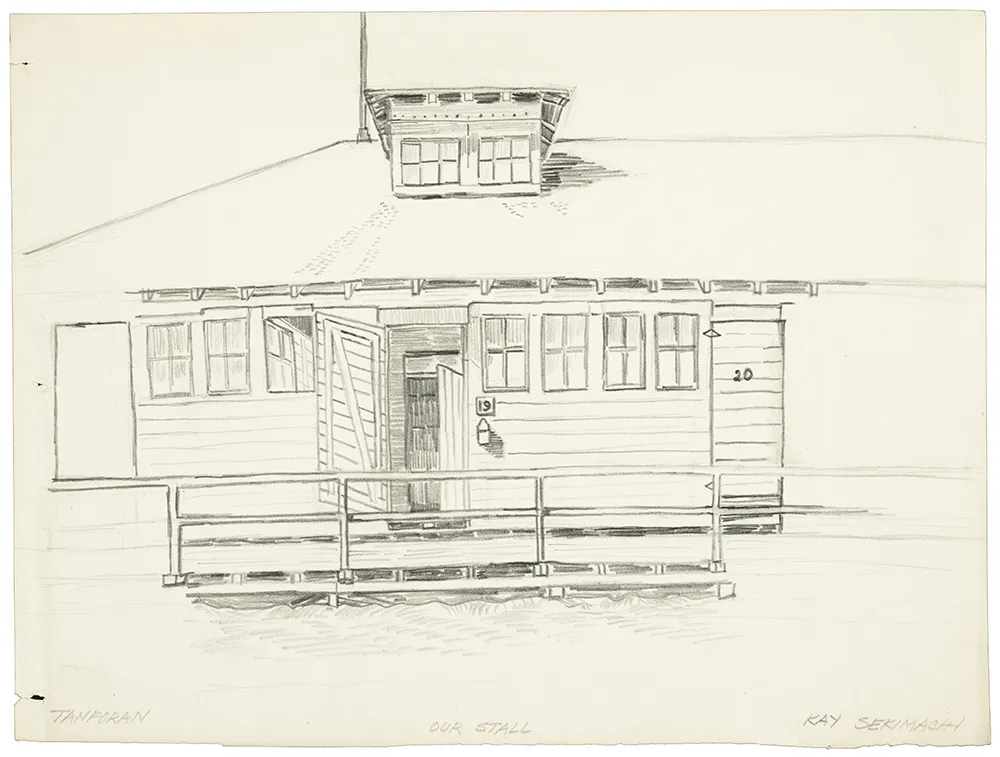

Citizen 13660 is the title of artist Miné Okubo’s acclaimed book with illustrations based on her experiences in internment camps during World War II. The number 13660 was also significant in that it was the collective “family number” assigned to Miné Okubo and her younger brother Toku; first at the central relocation station established at Berkeley’s First Congregational Church, where they were required to report in before being transported by train to Tanforan, the temporary camp on the grounds of a converted racetrack in San Bruno, California. For roughly half a year, Okubo and her brother lived in a horse stall that measured 20' x 9' and smelled of manure, where they slept on cloth sacks stuffed with hay.

Further compounding the hardships at Tanforan, Okubo’s family was scattered across internment camps in several states. Miné and Toku—one of her six siblings—were sent to the Topaz internment camp in Utah. Her father Tometsugu Okubo, a gardener and landscaper, was perceived as a threat due to his active involvement with Riverside Union Church after his wife’s death. The U.S. government suspected Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants not born in the states) who were active members of their communities of being disloyal to America and working as spies for Japan. He was sent to a detention camp in Fort Missoula, Montana—meant for individuals who were considered to be spies or “serious threats”—then to Louisiana. Okubo’s older sister Yoshi was sent to the relocation camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. The U.S. military drafted an older brother Senji from Riverside, California, not realizing he was Japanese American.

Like many of her fellow internees, Okubo was a second-generation Japanese American—also known as Nisei—born in the United States. She had never been to Japan, and spoke little Japanese. Okubo was also a gifted artist whose career had been off to a strong start prior to her period of incarceration. She attended Riverside Junior College in 1931 where an art professor noticed her talents and encouraged her to pursue it formally. With her professor’s recommendation, she was accepted at the University of California, Berkeley, and offered a scholarship. After graduating from Berkeley in 1935 with a B.A. and in 1936 with a Master’s in Art and Anthropology, Okubo won the Bertha Taussig Traveling Art Fellowship which, thanks to her thrifty spending, allowed her to study abroad in Europe for roughly two years. She traveled widely and studied under the painter Fernand Léger in Paris.

In late 1939, Okubo returned to the United States after receiving word that her mother was gravely ill. Her mother passed away soon after in 1940. Okubo returned to Berkeley with Toku and began working for the New Deal’s Federal Arts Project, creating mosaics and frescoes, and assisting artist Diego Rivera on his Treasure Island mural.

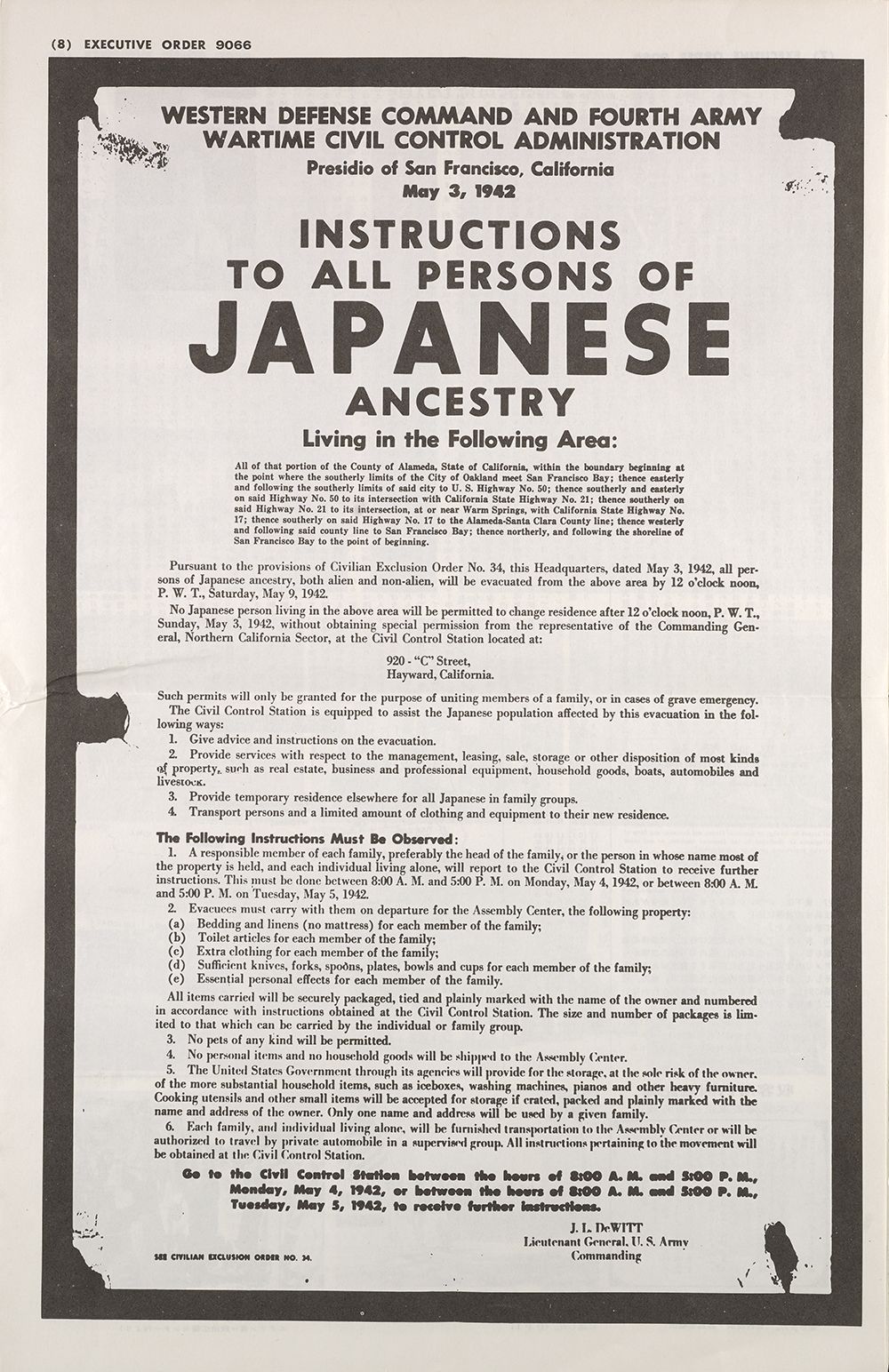

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which authorized the forced relocation of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast into internment camps. Okubo and her brother, who was a few weeks shy of graduation from Berkeley when the initial relocation occurred, stayed at the Topaz detention camp for roughly one and a half years.

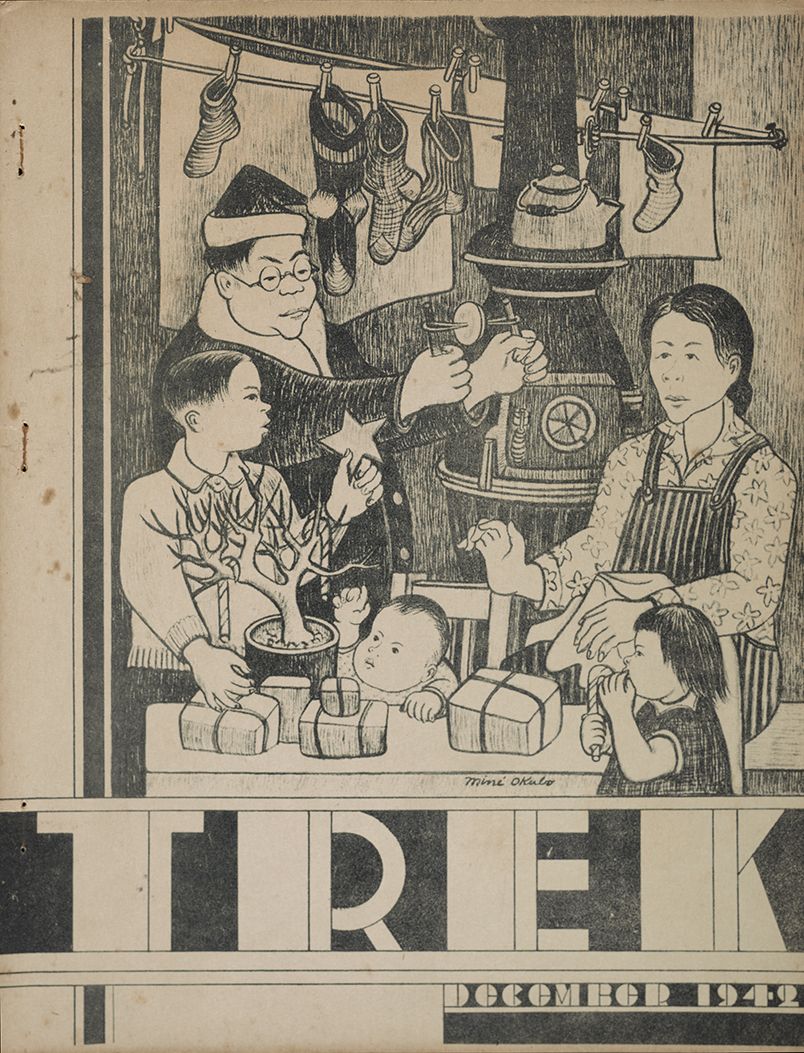

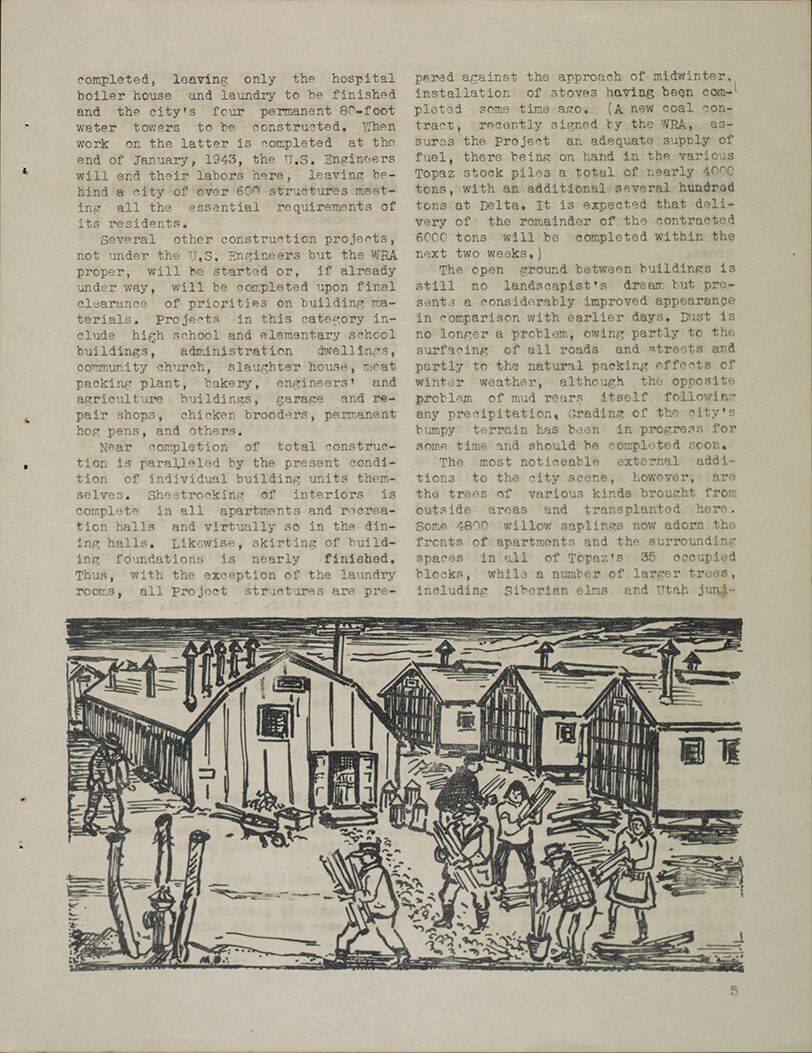

At Topaz, the internees were in a camp surrounded by barbed wire, living in barracks with communal bathing and dining facilities. While at Topaz, Okubo and several others created a literary magazine called Trek, for which she drew cover illustrations, and she taught art to interned children.

During her internment, driven by the knowledge that Americans outside the barbed enclosures would not believe what was occurring without proof, Okubo used her keen eye to observe and capture life inside the camps. Since cameras and photographs were forbidden to the internees, she recorded everything she could by drawing—often nailing quarantine signs on her barracks door to avoid interruption of her work—and was extraordinarily prolific: she made about 2,000 charcoal and gouache drawings total.

While still at Topaz, Okubo submitted one of her drawings of a camp guard to an art show in San Francisco. Her drawing won a prize and attracted the attention of editors at Fortune magazine, who hired her as an illustrator. Her brother Toku left the camp in June 1943 to work at a Chicago wax-paper company and later enlisted in the U.S. Army. In January 1944, Okubo left the Topaz internment camp and moved to New York and commenced her work for Fortune magazine’s special issue on Japan. Citizen 13660, which included text and 206 drawings, was published by Columbia University Press in 1946. Upon its publication, the New York Times book review described Citizen 13660 as “A remarkably objective and vivid and even humorous account. . . . In dramatic and detailed drawings and brief text, she documents the whole episode—all that she saw, objectively, yet with a warmth of understanding.”

While many reviews hailed the books lack of bitterness, Okubo did not mitigate the indignities she and her fellow internees suffered. Her strong sense of social justice also brought to light the demoralizing and reductive nature of the internment camps. Her New York Times obituary highlighted this, quoting Okubo: “The number was on suitcases and everything you owned, all the papers you signed. You became a number.” Citizen 13660 was the first book written by an internee about the camps; in the preface to the 1983 edition, Okubo wrote that she witnessed “what happens to people when reduced to one status and condition.”

Okubo lived in New York City for the rest of her life and worked as a freelance illustrator, later transitioning to painting full time and participating in group and solo exhibitions. In addition to Fortune magazine, her work was published in Life, Time, The New York Times, and she illustrated many children’s books. In 1981, Okubo testified before the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, urging the government to apologize for its treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. In 1984, Citizen 13660, by then recognized as an important document about the internment camps, received the American Book Award. In 1991, Okubo received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for Art

Okubo passed away in her apartment in Greenwich Village in 2001. Throughout her life, Okubo displayed an unwavering commitment to art and a fervor for portraying an unvarnished view of people and society. When asked about her internment camp experiences, she wrote, again in the 1983 preface to Citizen 13660, “I am a realist with a creative mind, interested in people, so my thoughts are constructive. I am not bitter. I hope that things can be learned from this tragic episode, for I believe it could happen again.”

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.