Acquisitions: Robert Alexander Papers and Temple of Man Records

:focal(491x450:492x451)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_alexbob_65125.jpg)

Temple of Man is not an edifice but a community of Beat poets, artists, and musicians founded in San Francisco in 1960 by assemblage artist Robert “Baza” Alexander (1923–1987). In 1968 Baza moved to a house on Cabrillo Avenue in Venice, California, which served as the Temple’s center of operations for some twenty years. The interior walls of the house were lined with a distinctive collection of works on paper that affirmed the Temple’s aesthetic principles and perhaps also its gift economy, as all of the works had been donated by participating artists. Here two or three generations of the Los Angeles Beat community gathered for poetry readings, musical performances, and meals. They also celebrated weddings, since Baza and others in the Temple were ordained priests happy to marry those who wanted a self-styled ceremony—say, in a hot tub. The tradition of ordained ministers in the Temple of Man officiating weddings continues to this day.

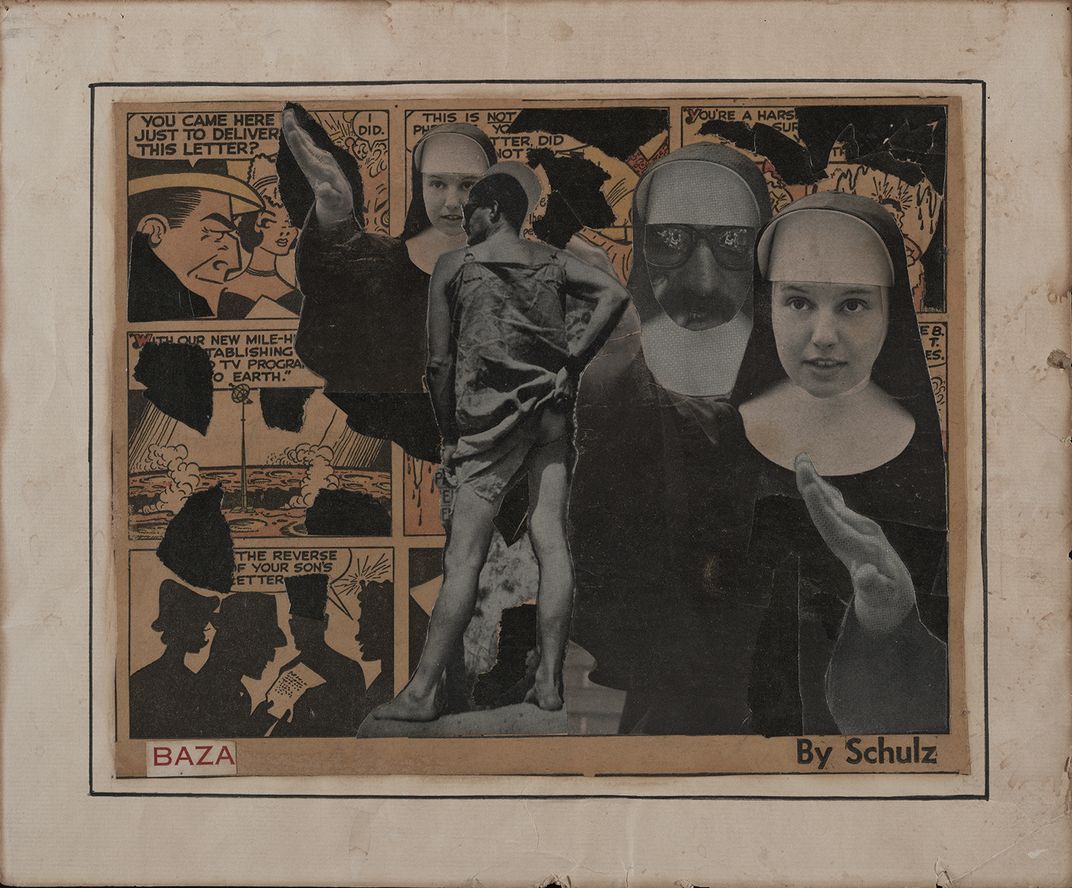

In 2017, the Archives received a substantial addition to the Robert Alexander Papers and Temple of Man Records donated in 1990 by Alexander’s widow, Anita Alexander. This significant addition, given by current Temple directors Yoav Getzler and George Herms, contains more than 100 collages, watercolors, drawings, and photographs. It also encompasses artist files containing correspondence, exhibition announcements and reviews, and photographs of artworks. Together these materials show the range of the California Beat aesthetic and how it evolved in the latter half of the twentieth century among Beat disciples. While some Temple artists, such as Bill Dailey, Tony Scibella, and Saul White, remain virtually unknown, the collection includes iconic examples of Beat-era visual culture such as Verifax photo prints by Wallace Berman, a George Herms Burpee Seed collage, and several of Ben Talbert’s erotic allegorical drawings. In addition, numerous works by Baza came with the donation.

Seeing this work unframed is a thrill because it allows a closer view and understanding of the artists’ materials and processes. But the Temple art collection also has broader significance, for it documents the Beats’ aesthetic strategies and their deep and lasting impact on California art of later generations, most obviously on conceptual and feminist practice of the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, among the records is a 1990 exhibition proposal by curator and gallerist Hal Glicksman that defines the Temple collection as an “archive of the origins of California modern art.”

Following the passing of Anita Alexander, the Cabrillo Avenue house was sold and the collection and records moved to Beat poet and Temple director Marsha Getzler’s bungalow in Benedict Canyon. George Herms recalls that when people told Getzler she was sitting on a goldmine, she would reply, “Gold, yes. Mine, no.” It had always been the community’s plan to keep the records and art collection intact and place them with an institution that would honor the Temple’s spirit, and in the Archives these.