Acquisitions: Naul Ojeda Papers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Franco-fig.-1-WR2.jpg)

The papers of Naul Ojeda (1939–2002) were organized and donated by his widow, Philomena “Pennie” Ojeda. Remarkably, the collection documents the Uruguayan-born artist’s entire career, despite that fact that conditions in his home country forced him into exile in France, Chile, and Mexico before he settled in Washington, DC, in the 1970s. Source materials and preparatory sketches related to Ojeda’s art, combined with correspondence with family and peers in Latin America, demonstrate that much of his work was informed by political turmoil in the region.

Ojeda had a deep appreciation for literature, and he provided artwork for both the Washington Book Review and the Washington Post’s Sunday Book World. His papers contain examples of these and other literature-inspired creations, such as an undated watercolor and ink portrait likely inspired by Federico García Lorca’s 1929 poem “Oda a Walt Whitman.” Birds and fish are common in Ojeda’s lyrical prints and paintings, often referring obliquely to political conditions throughout the Americas. In this watercolor, however, these creatures signal Whitman’s deep appreciation for nature, invoking a line from Lorca that reads, “Ni un solo momento, viejo hermoso Walt Whitman/he dejado de ver tu barba llena de mariposas [Not a single moment, lovely old man Walt Whitman/have I ceased to see your beard full of butterflies].”

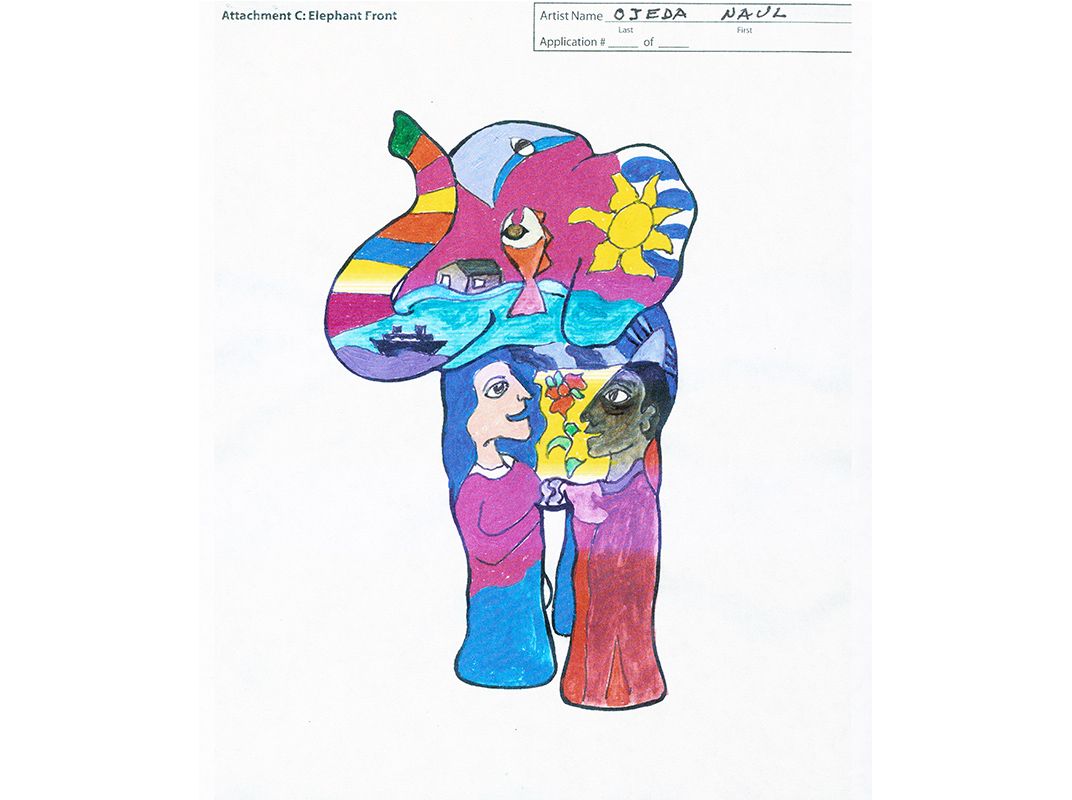

The artist was committed to democracy in the Americas throughout his lifetime. He provided images, for example, for important political organizations such as the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, and Grupo de Convergencia Democrática in Uruguay, a number of which are included in the artist’s papers. A file containing a copy of his proposal for the 2002 DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities project Party Animals demonstrates the playful side of Ojeda’s political engagement. The project called on artists to submit designs to decorate 100 elephant and 100 donkey sculptures (emblems of the US Republican and Democratic parties, respectively) intended for public display throughout the nation’s capital. One of four color sketches in the collection shows the front of Ojeda’s proposed elephant, to be painted in vibrant acrylics. The boat at the base of the animal’s trunk signals the artist’s advocacy for immigrants to the US, while the two smiling figures who comprise the elephant’s front legs may represent the reunion of loved ones following a period of exile—an experience that characterized many of Ojeda’s own relationships.

The Naul Ojeda Papers complement Ojeda’s two woodcut prints in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum: The Big Fish Dinner (1977) and Uruguay Recordandote (1979). Numerous sketches in the papers document his experiments with the human figure, animal imagery, and sun and moon icons, all significant themes in these woodcuts. Most importantly, Ojeda’s papers provide insight into the conditions that led many artists of Latin American origin to settle and work in the US. In this way, the materials add significantly to the Archives’ growing collections related to US Latino art.

This essay was originally published in the fall 2017 issue (vol. 56, no. 2) of the Archives of American Art Journal.