Nancy Knowlton

The renowned coral reef biologist leads Smithsonian’s effort to foster a greater public understanding of the world’s oceans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/knowlton_sept08_631.jpg)

Renowned coral reef biologist Nancy Knowlton was recently appointed to the Smithsonian's Sant Chair for Marine Science. She will lead the Institution's effort to foster a greater public understanding of the world's oceans. The magazine's Beth Py-Lieberman spoke with her.

Can you start by giving a short primer on how a coral reef grows and sustains itself?

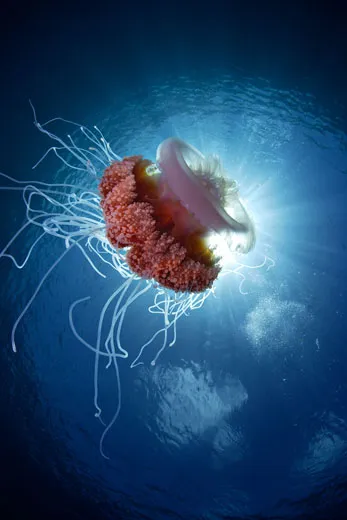

Coral reefs are created by corals and also by some other organisms—sometimes sponges, sometimes stony seaweeds. But corals are the main builders of coral reefs and they’re basically simple animals, rather like sea anemones. Each one has a little cup with a mouth and a ring of tentacles. They live in large colonies. The living part of the reef is just a very thin surface. Underneath is a skeleton which is secreted every . . . , well constantly, so that over the years, and decades, and millennia, you wind up with these massive structures that you can see from space. So a reef is sort of like a city; in the sense that it is always being constructed by living corals. But also, a reef is always being destructed by things that eat and chew on the rock, or turn the rock into sand. It’s always a balance between growth and erosion.

What threatens coral reefs today?

One culprit is overfishing, which wipes out a lot of herbivores. As a result, seaweed grows and smothers the corals. The second is declining water quality, caused by toxic materials and fertilizers that run off the land. The third is greenhouse gas emissions—especially carbon dioxide, which not only make the oceans too warm for reefs but also change the chemistry of the water, making it more acidic. And the more acidic the water, the harder it is for corals to deposit the skeletal structures that form the bulk of the reef. It’s sort of like when you’re mother told you not to drink so much Coca-Cola because it would dissolve your teeth. It’s the same kind of principle. That acidity, that increasing acidity, is making it much harder for corals to lay down a skeleton and it makes it, the skeleton, much more likely to dissolve in the future. So those are the three big ones: over fishing, poor water quality, and carbon dioxide because of its affect on temperature and acidification.

Are these changes a death knell?

We’re on a very serious downward trajectory for corals. In the Caribbean alone over the last three decades we’ve lost 80 percent of all corals. This is a level of destruction that rivals the devastation of tropical rain forests. We use to think the pacific was in better shape because it’s so much bigger and in so many places the density of human population was not so large. But it turns out that even in the Pacific, most reefs are, they are not as bad as the Caribbean yet, but a lot of them have degraded substantially, actually, to quite serious levels. So it means that globally things are already bad and then we have this projection of future increases in carbon dioxide emissions, which are extremely worrying for the future health of reefs. If people don’t change the way they’re doing things, reefs as we know them will be gone by the year 2050. It’s actually really depressingly unbelievable.

What would the world be like without coral reefs?

About a quarter of all marine species live on coral reefs. These species are a source of food, tourism income and potential biopharmaceutical products, including cancer drugs. Reefs also provide incredibly important shoreline protection against hurricanes and tsunamis.

A dead coral reef will protect it for a while, but because of what I said about reefs being in a sort of process of building and eroding, a dead reef actually will erode away to sand.

While snorkeling at a coral reef, say in the Florida Keys or the Hawaiian Islands, you’re likely to see a lot of different fish species. Does that mean the reef is a healthy, thriving one?

That’s actually an interesting question. And it’s a hard question too.. Sometimes you can have reefs that appear to have lots of things swimming around them, but the underlying corals are in poor condition. They are sick and dying. That means things superficially look good now, but the longer-term projection is much worse. On the other hand, sometimes things that have lots and lots of diverse organisms swimming or crawling around are, in fact, healthy reefs.

A recent study indicated a certain type of fish is necessary for good health.

It is the presence of the fishes that eat seaweed. Not all fish eat seaweed. So you can have lots and lots of fish, but if you selectively removed the seaweed eaters, it is not be good for corals. Usually when people fish, they usually start with big predators, so you lose the big fish—the sharks, the groupers and snappers, and you tend to lose the big herbivores. It’s called fishing down the food chain so you get to smaller fishes. It’s not so much the diversity of the fishes that you want to look at, as the number and size of the fishes that play critical ecological roles.

Yes I’ve been on a reef that has a green sort of slimy quality. What’s going on there?

That occurs because of either over fishing, poor water quality, or both. Reefs are more sensitive to the removal of seaweed eating fishes than they are to poor water quality. You wind up with too much seaweed if you have lots and lots of nutrients coming in and not enough fish taking the seaweed out. So it’s a kind of a balance. Either one of those processes can have bad affects on reefs. Reefs tend to be very sensitive to over fishing in contrast to water nutrients, which will have an impact but you have to have a lot of nutrients in order to see that affect. So it could be either of those two things or a combination of them both.

Should we even be snorkeling on reefs? Is that a problem?

I think we should be snorkeling and swimming on reefs. Because I think people only develop a passion for protecting things if they know what is at risk. I would hardly be one to say that we shouldn’t go near them. That said, its important to manage tourism properly. If you have a lot of people going onto reefs, stepping on reefs, collecting things from reefs, breaking corals off, or throwing anchors on top of reefs, that’s not good. It’s important to properly manage the numbers of people and their behavior when they’re in water. It’s also important to make sure that the hotels that support that tourism have good water treatment for the sewage that they release, and that they aren’t also feeding this large population of visitors critically important reef fish. That is ecologically sound tourism. But you can’t just let it develop willy-nilly. It has to be managed carefully. Otherwise, you end up with lots of people and not much reef.

What would a thriving coral reef look like?

A thriving coral reef has lots of living coral, often lots of three-dimensional structure, also a certain amount of pink stony material, which is actually a kind of stony seaweed actually, but it provides the surface that baby corals like to settle on. We like to see a lots of baby corals in places. Corals die just like other organisms, so you wind up with lots of empty spaces on reefs. But you want those spaces to be rapidly colonized by the next generation of corals. I’ve worked on a place in the middle of the central pacific called Palmyra Atoll and next to it is Kingman Atoll. They are protected by the United States as marine sanctuaries. When you go swimming on those reefs, 80 percent of that biomass is actually sharks and groupers. So we tend to think of a pyramid where there are lots of plants and then a smaller number of things that eat plants and a smaller number of things that eat those and then the top predators being the smallest of all. But it turns out that in the ocean what you have naturally is an inverted pyramid. It’s because the plants on reefs tend to be very small and have a rapid turnover. They’re not like very slow growing ancient trees. There are all these tiny things that are growing constantly and so turning over very, very fast. So as a consequence, you have more biomass at the top of the food chain with these big predators and less at the bottom. So you wind up normally with an inverted pyramid. We never see that because we’ve eaten everything at the top. For a completely pristine coral reef the fish community is dominated by top predators, things that are, you know, our size. There are very few places on the planet that you can see that because in most places the top predators are gone.

Can scientists even say what constitutes a healthy reef? Or has degradation been going on so long that a truly thriving coral reef hasn’t every really been observed our time?

The places that I was talking about where we saw those food webs dominated by top predators also had very lush coral reefs. They are far from people, or it is because for long periods they’ve been in protected areas—in those kinds of places, its still possible to see healthy reefs. And they give us a lot of hope in knowing that all is not lost and that there’s something we can do.

I detect a ray of hope, but I hear they call you Dr. Doom and your husband, Jeremy Jackson, also a renowned marine scientist, Dr. Gloom.

Jeremy and I, both, talk about the fact that we’ve lost 80 percent of the living coral on Caribbean reefs. And we’ve lost a lot of coral in the Pacific. And if we don’t change our ways, as humans, operating on the planet, we will lose all reefs. So it’s hard. You can’t just be cavalier. I mean we’re heading towards a catastrophe if we don’t change the way we manage the planet. And that’s not just coral reefs, its ocean resources in general. That said, we haven’t completely ruined the planet yet. And there are places on the planet that show us that it is possible to have healthy ecosystems with the right kind of management. So you can be optimistic in the sense that it is possible, but I mean, it is depressing to have watched. My husband is a little older than I am, and in the course of our professional careers, all the places that we have studied have essentially vanished as healthy reefs. It’s hard not to be Drs Doom and Gloom. On the other hand there is no point in that approach because everyone will say, “Oh well, what the hell, we’ve lost coral reefs.” And give up hope. So I think you have to make people realize just how incredibly serious the situation is, but also that there’s something that they can do about it.

If a Genie granted you three wishes, what would you wish for?

They’re kind of related wishes. One wish is that people would change their patterns of fossil fuel usage so we can get Co2 emissions capped and declining. If we don’t do that, in the long run, everything is hopeless. We have to do that. Reefs can’t grow in the level of acidity that is projected for business-as-usual Co2 emissions. Second wish is that we figure out ways to incorporate on a local level, sustainable agriculture, water quality treatment, and marine protected areas, so that we have conditions that favor reef growth. And then a more generic wish is that people would really, passionately, appreciate, and protect, the biodiversity of the planet, not just on coral reefs but the world at large.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)