Honoring Bill Moggridge

From designing the first laptop to defining human-computer interaction, Bill Moggridge spent his career breaking new ground in design and technology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120910044013moggridge_4701.jpg)

Most of the people I follow on Twitter come from the design and tech worlds, and so today my stream has coalesced almost entirely around the passing of Bill Moggridge, one of the most beloved and influential design leaders of our time, co-founder of IDEO, and most recently the director of Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. Moggridge blazed trails in industries that have become core engines of 21st-century culture—computers, product design, interaction design, and human-centered innovation.

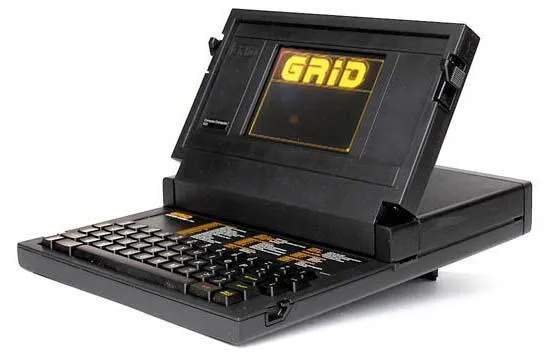

In the early ’80s Moggridge designed the first laptop computer, called the GRiD Compass, which of course heralded a sea change toward personal computing (a clip from Gary Hustwit’s Objectified film features Moggridge discussing the development of the machine). In the ’90s, he founded IDEO with David Kelley and Mike Nuttall, the global innovation company that popularized the notion of “human-centered design” and the collaborative, Post-it-note brainstorming process sometimes called “design thinking,” which seems to have become the favored sport of creative practitioners. In 2009, he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Cooper-Hewitt’s National Design Awards, and the following year took up the position of director at the Cooper-Hewitt, spearheading the museum’s major inside-out transformation, which is still in the works. Among the programming goals laid out by Moggridge for the Cooper-Hewitt was (and still is) the intention to have every American child experience design in school by the age of 12, giving them the opportunity and basis to aspire towards careers in design.

In many ways, Moggridge’s perspective on design is the same one we aspire to present here: it’s interdisciplinary, anthropological, and it cannot be isolated. It’s sometimes physical but not always. And it must be viewed and approached contextually, because good design solutions cannot be developed or understood without context. Not too long ago, I listened to an interview with Moggridge conducted by Debbie Millman, host of the excellent Design Matters podcast, and in it he summed up his outlook like this:

If you think about what people are most interested in…it doesn’t occur to them that everything is designed, that every building, everything they touch in the world is designed, even foods are designed nowadays. So the idea of getting that into people’s heads and helping them understand it, making them more aware of the fact that the world around us is something that somebody has control over and perhaps they could have control of, that’s a nice ambition.

At the end of her interview, Millman asked Moggridge, “What do you imagine for the future?” And he replied:

I’m hoping that design is still for people and that as designers we can create solutions and synthesize results which improve people’s lives and make things better in a general way. In the past we’ve thought about designing things for people—your PDA or whatever it might be—something that you use as an individual. A slightly more expansive context is to think more about the health and wellbeing of the person, so that…rather than thinking about the things, we’re thinking about the whole person or people. Similarly, when you think about the built environment, I think architecture has thought about buildings in the past, but as we move towards an expanding context for design, we find that we’re thinking more about social interactions, social innovations, as well as buildings. It’s not that one is replacing another, it’s expanding. So we’re thinking about those social connections as well as the built environment that we live in. And then if we think about the larger circle, sustainability is the big issue. In the past we’ve thought about sustainability as being a lot about materials: choosing the best material or designing for disassembly, that kind of thing. But now it’s absolutely clear that a sustainable planet is one that’s complete connected. Globalization has shown us that the effect of industrialization on the world is a planetary affair, so you can’t really think about just designing materials, you have to add to that the context of the entire planet, and that again is an expansion of context.

Numerous media outlets have posted beautiful tributes to Moggridge over the last couple of days, and the internet is full of videos, audio recordings, and written work by and about this visionary thinker. Millman’s full one-hour podcast is worth a listen, Cooper-Hewitt posted an extensive remembrance, Megan Gambino conducted a Q&A with Moggridge in Smithsonian Magazine last year, and if you want to hear his explanation on what design is, here’s a 55-minute keynote on the subject. Moggridge the man will be missed, but if there’s anything uplifting to extract from the sadness of loss, it’s that his breakthrough work and world-changing ideas will be kept very much alive by those who understand just how important his contributions have been.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)