Frito Pie and the Chip Technology that Changed the World

As we approach one of the biggest snack days of the year, meet the “Tom Edison of snack food” who brought us the “Anglo corn chip”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120130023033fritos-snack-food.jpg)

The curvy chips crinkle and crunch. Top the salty, golden corn chips with chili and you’ve got yourself a Frito pie, sometimes portioned out right inside the silvery, single-serving bag. The Frito pie is also known as a “walking taco,” “pepperbellies,” “Petro’s,” “jailhouse tacos,” or officially—under Frito-Lay North America, Inc.’s trademarked “packaged meal combination consisting primarily of chili or snack food dips containing meat or cheese corn-based snack foods, namely, corn chips”—the Fritos Chili Pie®. Call it what you will. It’s a soupy, creamy street food that’s recently entered the realm of haute cuisine.

Fritos got their start in Texas with the “Tom Edison of snack food.” The legend goes something like this, as Betty Fussell writes in The Story of Corn: “In San Antonio in 1932, a man named Elmer Doolin bought a five-cent package of corn chips at a small café, liked what he ate and tracked down the Mexican who made them.” In another version of the story, Clementine Paddleford writes:

The flavor tickled his fancy, it lingered in memory. He found the maker was a San Antonian of Mexican extraction who claimed to be the originator of the thin ribbons of corn. The Mexican, he learned, was tired of frying the chips; he wanted to go home to Mexico and would be glad to sell out.

The café was more likely an icehouse, and the man who made the corn chip was named Gustavo Olquin, according to C.E. Doolin’s daughter Kaleta, who wrote a 2011 book Fritos Pie: Stories, Recipes, and More. She says her father worked briefly as a fry cook for Olquin and paid Olquin and his unnamed business partner $100 for a customized, hand-operated potato ricer, their 19 business accounts and the recipe for fritos—the patentable Anglo re-branding of Mexican fritas, or “little fried things.” Doolin borrowed $20 from the business partner; the rest came from his mother, Daisy Dean Doolin, who hocked her wedding ring for $80.

C. E. Doolin tinkered around with the recipe, mechanized the chipping process, and, in 1933, patented a “Dough Dispensing and Cutting Device” and trademarked the Fritos name. He worked on breeding custom varieties of hybrid corn. Doolin invented a “Bag Rack” and adopted the now-familiar practice of deliberately misspelling products to draw attention—“Krisp Tender Golden Bits of Corn Goodness.”

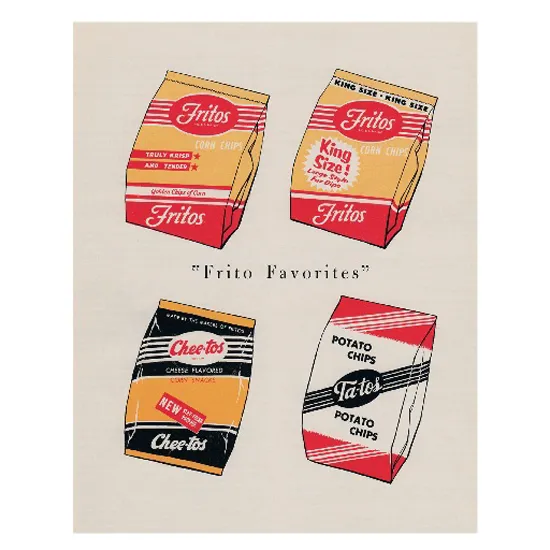

Whether fritas become fritos as an accidental Anglofication or as a deliberate “sensational spelling”—in the vein of Dunkin’ Donuts, Froot Loops, Rice Krispies—remains something of an open question. Prior to Doolin’s trademark, though, fritos does not appear to have referred to fried corn chips in Mexican Spanish. Either way, snack foods with distinctive, masculine “Os” persevered: Doolin would go on to create Cheetos and Fritatos; the company he founded would introduce Doritos and Tostitos.

What’s remarkable in retrospect is that he appears to have intended Fritos as a side dish or even an ingredient. In fact, the first recipe Daisy Dean Doolin came up with in 1932 was a “Fritos Fruit Cake”; its ingredients include candied fruits, pecans and crushed Fritos. Another early recipe for a company contest submitted by the woman who would later became C.E. Doolin’s wife, Mary Kathryn Coleman, described a “Fritoque Pie,” a chicken casserole with crushed Fritos. Her prize: $1. (This recipe has been lost and the lack of documentation probably contributes to competing claims about Frito pie’s origins at a New Mexico Woolworth’s in the 1960s.)

Pies aside, the fried corn chips became a pantry staple and an easy-to-use replacement for cornmeal, salt, and oil. Their versatility was practically unlimited. Advertisements from the 1940s said, “They’re good for breakfast, lunch, snack-time and dinner.”

Even more surprising for a man who revolutionized American corn chips and presaged the meteoric rise of the “Anglo corn chip,” which firmly cemented itself when Frito-Lay’s unveiled Doritos in 1966: Doolin did not eat meat or salt. He was a devoted follower of Herbert Shelton, a Texas healer, who ran for president on the American Vegetarian Party ticket.

I thought this transformation of Fritos loosely mirrored that of the Graham cracker, a whole-wheat health food that evolved into a sugary snack. I called his daughter, Kaleta Doolin, and asked about the apparent disconnect. “Fritos have always been a salty snack,” she said, “unless you’re at the factory and take them off the assembly line before they go through the salter, which is what we did.”

As much scorn and derision as today’s leading nutritional gurus heap onto processed foods, it’s worth noting that Fritos arrived here by way of a Mesoamerican staple and their invention and flavor owes a debt to one of the greatest food processing technologies ever invented: nixtamalization. The 3,000-year-old tradition adding calcium hydroxide—wood ash or lime—so greatly enriches the available amino acids in masa corn that Sophie Coe writes in America’s First Cuisines that the process underlies “the rise of Mesoamerican civilization.” Lacking this technology, early Europeans and Americans (who considered corn fit for slaves and swine) learned that eating a diet exclusively based on unprocessed corn led to pellagra, a debilitating niacin deficiency causing dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and death.

As we approach one of the biggest snack days of the year and as “Anglo corn chips” continue to make up an increasing percentage of the snack foods market, perhaps it’s also worth celebration the incredible corn processing technology that brought us masa, tortillas fritas, Late Night All Nighter Cheeseburger-flavored Doritos and, of course, the Frito pie.