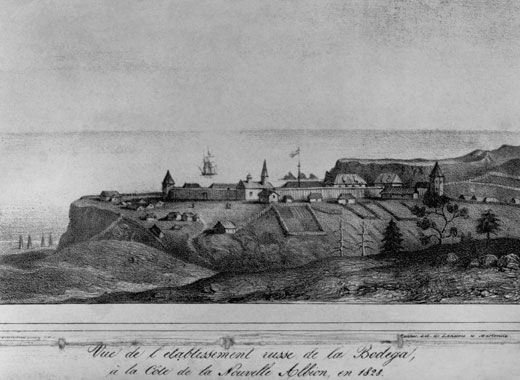

When Russia Colonized California: Celebrating 200 Years of Fort Ross

A piece of history on the Pacific Coast was almost lost to budget cuts, until a Russian billionaire stepped in to save the endangered state park

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fort-Ross-State-Park-Russian-Orthodox-Chapel-631.jpg)

By afternoon, the fog has burned off the hillsides at California’s Fort Ross State Park. The wood-burning oven is loaded with hearty loaves of bread, little boys are climbing on the cannons and dancers hold hands as they circle in the grass, singing a lilting Russian folk song.

The women and girls wear long, brightly patterned dresses, with strands of amber beads around their necks and their hair swept up under colorful scarves-- festive attire for a weekend gathering. The men and boys are dressed in simple white tunics, belted at the waist. Except for the intermittent murmur of traffic winding along the Pacific Coast Highway nearby, this remote stretch of coastline about 90 miles north of San Francisco looks and sounds much as it must have two centuries ago, when the Russian-American Company, a mercantile firm chartered by the Tsar, chose the site for the empire’s only colony in what would become the contiguous United States.

This year,which marks Fort Ross’ bicentennial, has been packed with lectures, performances and visits from Russian tall ships. But the main event comes on July 28 and 29, when the park will celebrate 200 years of Russians in America with a heritage festival expected to draw up to 3,000 people.

It’s a celebration that almost didn’t happen. In 2009, California, seeking to cut costs in the midst of a financial crisis, marked more than 200 state parks for closure. Among them was Fort Ross.

* * *

The American history of the site began in 1841, when the Russian colonists gave up their enterprise and sold the colony to pioneer John Sutter, who transported its equipment and supplies to his own fort in Sacramento. The area served as ranch land for more than 60 years, until California designated it as a state historic park in 1906. By that time, the colony’s remaining structures had fallen into disrepair, and most of the buildings visitors see today are 20th-century reconstructions.

Within a weathered stockade built from redwood timber are barracks, officers’ quarters, and a small, unadorned Russian Orthodox chapel with a simple belfry. The only original building from the Russian era is the home of the colony’s last manager, Alexander Rotchev, a one-story family dwelling stocked with reconstructions of period furniture and housewares. It has survived a patchwork of additions, a second life as a hotel and a 1971 arson fire. Today, it is suffering leaks, among other ailments.

Although Fort Ross had the appearance of a military installation, it was never involved in warfare. For three decades, Russian colonists lived and intermarried with Native Americans, traded with Spain and the United States, and made a living through agriculture, otter-hunting and shipbuilding.

“This is a place where a colonial power came in and squatted for 30 years and it was peaceful,” says Tom Wright, a retired schoolteacher who sits on the board of the Fort Ross Conservancy, the non-profit group that organizes programs at the state park and raises money to support it. “Everything sort of came together out here. This was the farthest outpost for the Russians and the farthest outpost for the Spanish.”

Although it is thousands of miles from the motherland, for many of California’s Russian-Americans it feels like a link to their native soil. It was these devotees who struck up a call to preserve Fort Ross—a call that was answered by an unlikely benefactor.

* * *

Konstantin Kudryavtsev remembers feeling immediately at home when he first visited Fort Ross a dozen years ago, soon after immigrating to the United States.

“I liked it from the first sight,” says Kudryavtsev, a Silicon Valley software engineer who dressed for the annual fall harvest festival in a rubakha, a loose-fitting tunic in the style of a 19th-century Russian nobleman.

Kudryavtsev, a conservancy board member, compares the restored settlement, with its rough-hewn wooden buildings, simple chapel and stark terrain, to villages in Eastern Russia.

“It was so similar to the place where I grew up in Siberia,” he says. “The nature is very similar. The buildings smell the same.”

“When you come to a place where you’re a stranger, it’s natural, trying to look for some traces, some history of people who came from the same country,” says his wife, Geliya Kudryavtseva. “When we found Fort Ross as a family and started volunteering, we found friends.”

The Kudryavtsevs had found a place where Russian-Americans and their children could meet to celebrate their heritage. But they and other Russian-Americans were dismayed when they learned that California was planning to close Fort Ross.

“I felt, my God, I have to ring the bell everywhere. It’s appalling!” says Natalie Sabelnik, president of the Congress of Russian Americans, a nationwide association based in San Francisco that promotes the interests of Americans of Russian descent. “This isn’t just a park, this is a monument and a testament to the Russians that came and their struggles. How can this be taken away?”

Sabelnik, who was born in Shanghai to Russian parents in the 1940s and grew up in a close-knit Russian community in San Francisco, remembers visiting Fort Ross as a child for annual church picnics.

“For many years, you couldn’t visit Russia, you couldn’t write to relatives in Russia,” she says, recalling the cold war years. “But here was a piece of Russia you could touch.”

Sabelnik’s group got the word out about Fort Ross. They circulated petitions and sent them to then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, with several thousand signatures from Russian émigrés living as far away as South America.

Word of Fort Ross’ plight soon made it to the Kremlin, and in mid-2009 the Russian government dispatched its ambassador, Sergey Kislyak, to the park for a well-publicized visit. Kislyak wrote letters to Schwarzenegger, imploring him to keep Fort Ross open; the San Francisco Chronicle reported on the trip and on Kislyak’s appeals.

And that is how Olga Miller, CEO of the New York office of the Russian conglomerate Renova, first learned about the plight of Fort Ross. “I was told by Renova Moscow that this was something we should look into,” says Miller. “They knew more about it in Russia than we did here—it was an interesting paradox.”

Renova Group, a sprawling private company, has operations in mining, energy, technology and finance. Its primary shareholder is Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, worth more than $8 billion and best known in the United States for buying up a trove of Fabergé eggs from the Forbes publishing family in 2004.

With business interests around the world, Renova was interested in improving relations between Russia and the United States, and saving Fort Ross seemed to fit that mission.

In 2010, Renova signed an agreement with Governor Schwarzenegger, and since then it has put more than $1.2 million toward preserving and improving the park.

At first, Renova simply wanted to help keep the park open, which costs about $800,000 a year. But they soon learned that Fort Ross needed more than that. Despite its devoted membership, Miller says, the Fort Ross Conservancy was struggling to build support and name recognition for the isolated site. The park’s small museum and visitors’ center needs to be updated, and some of the historic buildings are badly in need of repair. And because it is too expensive to staff the park every day, Fort Ross is currently open only on weekends and holidays and on Fridays during the summer.

“We are trying to create a master plan, if you will, and working with state parks and [the conservancy] to create a sustainable future for the park,” Miller says. “We feel it is very important to bring Fort Ross to a higher level.”

That has not been easy, Miller admits. Coming from the corporate world, she and other Renova officials expected to see results quickly. But California’s government does not work that way, and in the U.S. any change to a historic site requires layers of approvals and impact studies.

“It’s a very bureaucratic system—even more bureaucratic than anything I’ve seen in Russia,” Miller says.

Linda Rath, the superintendent of the California State Parks sector that includes Fort Ross, acknowledges the clash of cultures.

“It’s frustrating for them,” she says, of Renova. “It’s a great opportunity, but it’s hard to explain why it takes so long to get projects even started.”

As its budget has been whittled away, the parks department has postponed more than $8 million in necessary renovations at Fort Ross over the past decade, Rath says. The arrangement with Renova will allow some of that work to happen soon.

Though some Californians may be uneasy about Renova’s involvement, worrying that it means Fort Ross will become a commercial enterprise, Rath says that the conglomerate is not taking over the park.

“State Parks are still managing the parks,” she says. “We’re very careful with the branding. We’re not plastering banners all over the place. We’re not putting a billboard up.”

Fort Ross will retain its character, asserts Sarah Sweedler, the conservancy’s director.

“It’s not an East Coast historical theme park,” she says. “It’s more community oriented and it’s a reflection of the community.”

With the future more secure than it was just a few years ago, Fort Ross enthusiasts are looking forward to July’s anniversary celebration.

On a recent weekend, Robin Joy, the park’s chief interpretive specialist, watches a group of folk dancers with pleasure. She has worked at Fort Ross for more than two decades, through lean times and revitalizations.

“They actually make and create a life for Fort Ross,” she says, of the Russian families. “It’s such a good atmosphere that they bring.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)