When Casanova Met Mozart

The world’s most notorious lover lived in Prague at the same time as the composer, but the mystery remains: did they collaborate on a famous opera?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Casanova-Prague-631.jpg)

One of the vital epicenters of European culture, Prague has survived the wars of the last two centuries almost entirely intact. Today, the most atmospheric part of the city’s historic Old Town is the Malá Strana, or “Little Quarter” on the west bank of the river Vlatava: its quiet back alleys, which wind up past mansions and churches to Prague Castle, still have the haunted, Brothers Grimm appearance they had in the late 18th century. Here, it’s easy for visitors to still picture the likes of Giacamo Casanova, albeit in his twilight years, navigating Prague’s cobbled paths in his breeches and powdered wig, on one of his visits from nearby Castle Duchcov. At first, the somber medieval style of the Czech capital might seem an odd retirement choice for the ebullient Venetian who fled his beloved home city in 1783 after he offended powerful figures there. But look a little closer and Casanova’s spirit is everywhere. “Prague is a Gothic city that was baroquized by Italian artists,” explains Milos Curik, a Czech cultural guide. “This was where the Italian Renaissance first reached northern Europe.”

Today, Malá Strana’s ancient buildings still conceal flamboyant interiors. Peer through shuttered windows and one is likely to see designer bars that would not be out of place in Barcelona or New York. On my recent visit, I woke up inside a 14th century monastery adorned with Eastern art: urban conservationists have overseen its renovation by Mandarin Oriental, using an exotic blend of Czech and Asian influences. Even the hotel spa was built on the foundations of a medieval chapel, which can still be admired through the glass floor. And Casanova himself would have been gratified to learn that the staff offer a booklet on “The Ten Best Places to Kiss in Prague” – the Charles Bridge at dawn is particularly auspicious – and a Venetian-style Carnival is now a highlight of Prague’s winter season, complete with masked balls, street theater and parades.

But of all the arts, music has always been central to the city’s reputation. One of the most beguiling stories about Casanova’s sojourn in Bohemia – now part of the Czech Republic – is that he met Mozart in Prague in 1787, and that he worked on the libretto of Don Giovanni, the great opera about a compulsive Lothario not at all unlike Casanova himself. Today, tracing the little-known saga provides a marvelous key to the city.

To follow the Casanova trail, my first stop was the Italian Cultural Institute, which was founded as a Jesuit-run hospital in the early 1600s, complete with a serene cloister and a frescoed church. Thanks to its extensive library, the edifice soon developed into a gathering point for expatriate Italians, who began to live along the same street, Vlašská Ulice. “It’s 99.9 percent certain that Casanova came to this building the moment he arrived in Prague,” said the director, Dr. Paolo Sabatini. “It was the heart of the Italian community in the city. Bohemia was a great refuge for Italians. There were Italian artists, writers, technicians, engineers, many of them escaping charges of the [Roman] Inquisition.”

According to biographer Ian Kelly, author of Casanova: Actor Love Priest Spy, Casanova first met an old friend from Venice Lorenzo da Ponte, a fellow libertine who was now Mozart’s librettist, having written both The Magic Flute and The Marriage of Figaro. Italian opera was little short of a craze in Prague at the time, and Casanova had long been enraptured by the art form. (One of his most memorable episodes in his memoir, The Story of My Life, is his youthful affair with a female opera singer who was masquerading as a castrato). Casanova and da Ponte regularly attended concerts at the rural retreat of local arts patrons Josefina and Fratišek Dušek. Called the Betranka, this villa on the outskirts of Prague was where they mingled with other artistic celebrities – including, it is believed, the 31-year-old Mozart.

Mozart first came to Prague with his wife Constance in January, 1787, for a performance of The Marriage of Figaro. He was delighted to discover that his opera was given a euphoric reception in the city, whereas in Vienna he had fallen out of fashion. “Here they talk about nothing but Figaro,” Mozart recorded in his diary. “Nothing is played, sung or whistled but Figaro. Nothing, nothing but Figaro. Certainly a great honor for me!” As a result, he decided to premiere his new work, Don Giovanni, in the city. He returned to Prague in October with da Ponte’s unfinished libretto in hand, and moved into the Bertramka, at the invitation of the Dušeks, to furiously complete it.

Today, the Bertramka is open to the public as a small Mozart Museum, so I took a tram to the suburbs of Prague. The estate is now surrounded by roaring highways, although once inside the gates, it remains an enclave of serenity, with gardens that still host summer concerts. The exhibits are sparse – in 2009, most of the furnishings and instruments were moved to the Czech Music Museum in Malá Strana, including two pianos played by Mozart himself – but the villa itself still exudes an elegant, artistic ambiance. The sole employee sells a series of engravings of famous visitors, who included a virtual Who’s Who of the 18th century cultural elite: Along with Mozart, da Ponte and Casanova, the Dušeks hosted the young Beethoven and German poet Goethe.

The claim that Casanova worked on Don Giovanni was made back in 1876 by Alfred Meissner in his book Rococo Bilder, based on notes made by his grandfather, who was a professor and historian in Prague and was the confidant of musicians at the opera’s 1787 premiere at the Estates Theater. According to the musicians, Casanova visited the theater during rehearsals in October, when Mozart was doling out the last pieces of the music in disjointed fragments. The cast members became so frustrated that they locked Mozart in a room and told him he would not be freed until he finished the opera. Casanova apparently persuaded the staff to release the composer, who completed the overture that night, while Casanova fine-tuned the libretto in several key scenes.

There is strong circumstantial evidence to support Meissner’s report: We know that da Ponte was not in Prague in October, when the last-minute changes were made to the libretto, but Casanova was. However, the account took a more substantial form in the early 1900s, when researchers discovered notes amongst Casanova’s papers from Castle Duchcov that appeared to show him working on a key scene in Don Giovanni.

While the manuscript of Casanova’s memoir now resides in Paris, his personal papers have ended up in the Czech state archive, a hulking edifice in a bleak, Communist-era landscape far from Prague’s charming Old Town. My taxi-driver got lost several times before we located it. Once inside, a security guard directed me to a shabby antechamber, where I had to call the archivists on an antique black telephone. An unshaven clerk in a hooded jacket first helped me fill out the endless application forms in Czech, before finally I was taken to a windowless, neon-lit research room to meet the head archivist, Marie Tarantová.

Despite the Cold War protocol, everyone was very helpful. Tarantová explained that when the Communists nationalized Czech aristocratic property in 1948, the state inherited a vast cache of Casanova’s writings that had been kept by the Waldstein family, who once owned Castle Duchcov. “We have Casanova’s letters, poems, philosophical works, geometry works, plans for a tobacco factory, even treatises on the manufacture of soap,” she said, of the wildly prolific author. “There are 19 cases. It’s impossible to know everything that’s in there. I’ve never counted the number of pages!”

Soon Tarantová laid before me the two pages of notes covered in Casanova’s elegant, distinctive script; in them, he has reworked the lines of Act II, scene X, of Don Giovanni, where the Don and his servant Leporello have been discovered in a ruse that involved swapping clothes and identities. “Nobody knows if he was really involved in writing the libretto or was just toying with it for his own amusement,” said Tarantova. According to biographer Ian Kelly, “the close interest and precise knowledge of the newly performed text argues in favor of (Casanova) having been involved in its creation.” With da Ponte away, it is quite feasible that Mozart would have called on the 62-year-old Italian writer, whose reputation as a seducer was known throughout the courts of Europe, to help with the text. Casanova was also in the audience when the opera premiered on October 29. “Although there is no definitive proof that he worked on the libretto,” sums up the American Casanovist Tom Vitelli, “I think Meissner’s account is likely true, at least to some extent.”

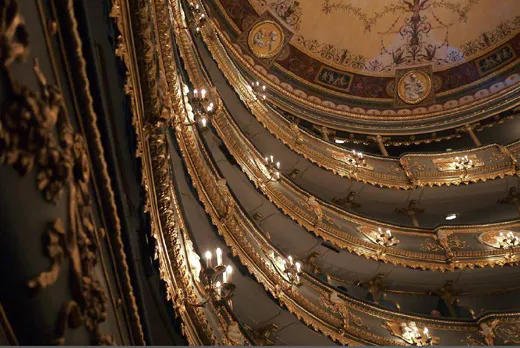

On my final evening, I attended a performance at the majestic Estates Theater, where Don Giovanni still plays in repertory. The gilded edifice is one of the last intact 18th century opera houses in Europe, and was used as a set for Amadeus and the Beethoven biopic Immortal Beloved. A small bronze plaque in the orchestra pit marks the spot where Mozart stood to conduct that night in 1787. (Its interior has changed in only one respect: the red-and-gold color scheme was changed to blue-and-gold after the Velvet Revolution of 1989 – red was associated with the hated Communist regime.)

At this historic performance – which was a huge success, prompting a standing ovation – Casanova sat in a box seat in the wings. When later asked by a friend whether he had seen the opera, Casanova allegedly laughed, “Seen it? I practically lived it!” The very next year, he began to write his own romantic memoirs in Castle Duchcov.

A contributing writer to the magazine, Tony Perrottet is the author of Napoleon’s Privates and The Sinner’s Grand Tour: A Journey through the Underbelly of Europe; www.sinnersgrandtour.com

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)