What Killed the Mammoths of Waco?

Sixty-six thousand years ago, this national monument was the site of a deadly catastrophe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/07/6c0789b4-f9a0-497e-9ced-f8908886c901/digshelterinterior.jpg)

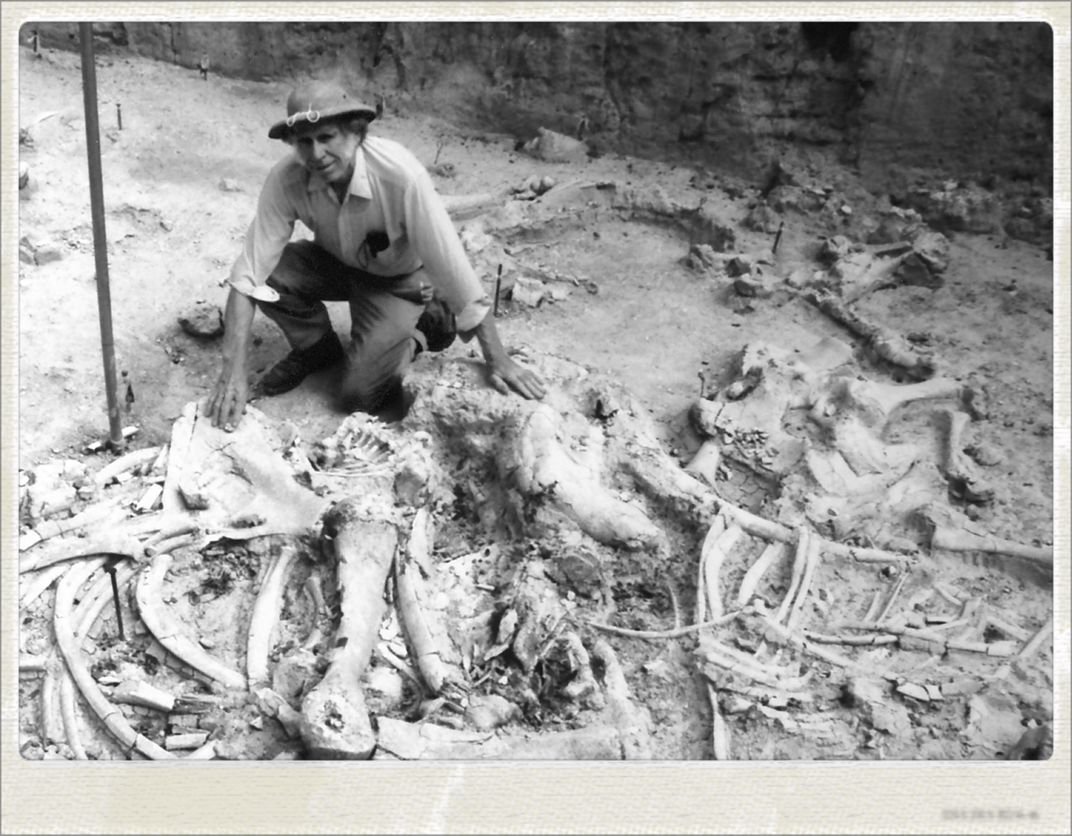

For two decades, a circus tent stood on the outskirts of Waco, Texas, not far from the point where the Bosque and Brazos rivers converge. But the real elephant attraction was below: Columbian mammoths, still preserved in their death pose, more than 60,000 years after floodwaters left them buried in mud.

The Waco Mammoth National Monument, its circus digs now replaced with a climate-controlled shelter and visitor center, became one of the country’s newest national monuments in July. The first hints of the Ice Age graveyard were discovered by accident in 1978, when two 19-year-olds looking for arrowheads along a dry riverbed found mammoth bones instead. They alerted paleontologists at Baylor University, sparking an excavation that yielded surprisingly rich finds. Within a decade, 16 Columbian mammoths were uncovered and lifted out of the ground in plaster jackets. A second phase revealed six more mammoths, a camel and the tooth of a saber-tooth cat.

The deposit is unique because it preserves a nursery herd—at least six adult females and ten juveniles—that died together in a single event. Unlike the Hot Springs Mammoth Site in South Dakota, where over 60 juvenile and adolescent male Columbian mammoths plummeted to their deaths over the course of many years, the Waco site bears witness to a single, catastrophic event. And the absence of arrowheads and other archaeological remains suggests that the bones aren’t a heap of Paleo-Indian leftovers—this was a mass grave from a natural disaster.

How—and when—did the animals die? New research found a likely answer within the sediments that entombed the creatures. The paper, which was recently published in Quaternary Research, concludes that the original 16 mammoths from the herd were likely standing in the wet, sandy sediment near the confluence of the two rivers when a storm hit. As floodwaters rose, the animals might have been trapped between the river and the ravine’s walls. At 12-to-14 feet tall and weighing seven to eight tons, Columbian mammoths weren’t exactly agile. Perhaps they couldn’t climb the steep slopes to escape in time. Some might have even been trapped in a mudslide. Other mammoths seem to have died in a similar storm while visiting the same area years later.

Earlier radiocarbon dates had suggested that the main mammoth-killing event took place about 29,000 years ago. But geologist Lee Nordt and his co-authors found that the mass death was actually much earlier—around 66,000 years ago. To do so, they used a dating technique known as optically stimulated luminescence, or OSL, which measures the time since a mineral sample was last exposed to sunlight or intense heat. The new date falls within an especially chilly period when the grasslands of central Texas were about seven degrees cooler than they are today.

The difference may seem small, but over the span of many years, cooler average temperatures can affect rainfall, soil conditions and even animal growth. This could help explain why the Columbian mammoths—a species better adapted to warm environments than woolly mammoths—look a little stunted and slightly malnourished at Waco. “Maybe it’s because it was a much colder period and they were struggling a little bit,” Nordt tells Smithsonian.com. The animals’ condition lends credence to the new date—after all, it would be harder to explain why the animals were in poor health if they died during a warmer period 29,000 years ago.

Though the mammoths appear to have died within minutes, the fossil deposit’s move from private hands to national monument was decades in the making. Initial excavations were kept under wraps, and in 1996, landowner named Sam Jack McGlasson donated his portion of the site to the City of Waco. Through gifts and purchases, Baylor University acquired another 100 acres around the fossils. In the mid-2000s, local advocates formed the Waco Mammoth Foundation and raised over $4.5 million to build a permanent shelter over the bones. While two bids to make it a unit of the National Park Service stalled in Congress, the site became a fully operational tourist attraction on its own. By the time U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell visited the site for its official dedication in October, she said it was like being presented “a national park in a box.”

“To get someone to feel connected to a lump of bones is a challenge,” Raegan King, manager of the site, tells Smithsonian.com. “It’s important for people to understand not only how these animals died but how they lived.” Lucky for King, the Waco site has shed light on the elusive social lives of mammoths, who seemed to have roamed in herds much like those of modern-day African elephants.

Only two-and-a-half acres of the site have been excavated so far. King hopes future visitors will get to witness paleontology in action, as the potential for new discoveries is “really, really good.” In the future, says King, visitors may even be able to watch museum workers remove mammoth fossils in an on-site lab.

Greg McDonald, a senior curator of natural history with the National Parks Service, agrees that there’s plenty of potential for additional research. He tells Smithsonian.com that construction workers hit bone when they were putting in foundations for the permanent dig shelter, and fossils seem to erode out of the ground every time there is a rainstorm. Next, researchers hope to discover just why the site was so attractive to prehistoric animals.

“I’m a museum person and I love mounted skeletons, but one of the reasons why I came to the Park Service is that we can provide a broader context for seeing something in its original position that you lose once you take it out of the ground,” McDonald says. “I think the folks in Waco have something to be very proud of.”