Mystery of the Varna Gold: What Caused These Ancient Societies to Disappear?

Treasure found in prehistoric graves in Bulgaria is the first evidence of social hierarchy, but no one knows what caused the civilization’s decline

:focal(1103x1016:1104x1017)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/4b/d74b4d85-4b89-4984-a2d2-9cd02b92a3fc/sqj_1604_danube_gold_01.jpg)

Perhaps you’d like to see the cemetery?” says archaeologist Vladimir Slavchev, catching me a bit off balance. We’re standing in the Varna Museum of Archaeology, a three-story former girls’ school built of limestone and brick in the 19th century. Its collections span millennia, from the tools of Stone Age farmers who first settled this seacoast near the mouth of the Danube to the statues and inscriptions of its prosperous days as a Roman port. But I’ve come for something specific, something that has made Varna known among archaeologists the world over. I’m here for the gold.

Slavchev ushers me up a flight of worn stone stairs and into a dimly lit hall lined with glass display cases. At first I’m not sure where to look. There’s gold everywhere—11 pounds in all, representing most of the 13 pounds that were excavated between 1972 and 1991 from a single lakeside cemetery just a few miles from where we’re standing. There are pendants and bracelets, flat breastplates and tiny beads, stylized bulls and a sleek headpiece. Tucked away in a corner, there’s a broad, shallow clay bowl painted in zigzag stripes of gold dust and black, charcoal-based paint.

By weight, the gold in this room is worth about $181,000. But its artistic and scientific value is beyond calculation: The “Varna gold,” as it’s known among archaeologists, has upended long-held notions about prehistoric societies. According to radiocarbon dating, the artifacts from the cemetery are 6,500 years old, meaning they were created only a few centuries after the first migrant farmers moved into Europe. Yet archaeologists found the riches in just a handful of graves, making them the first evidence of social hierarchies in the historical record.

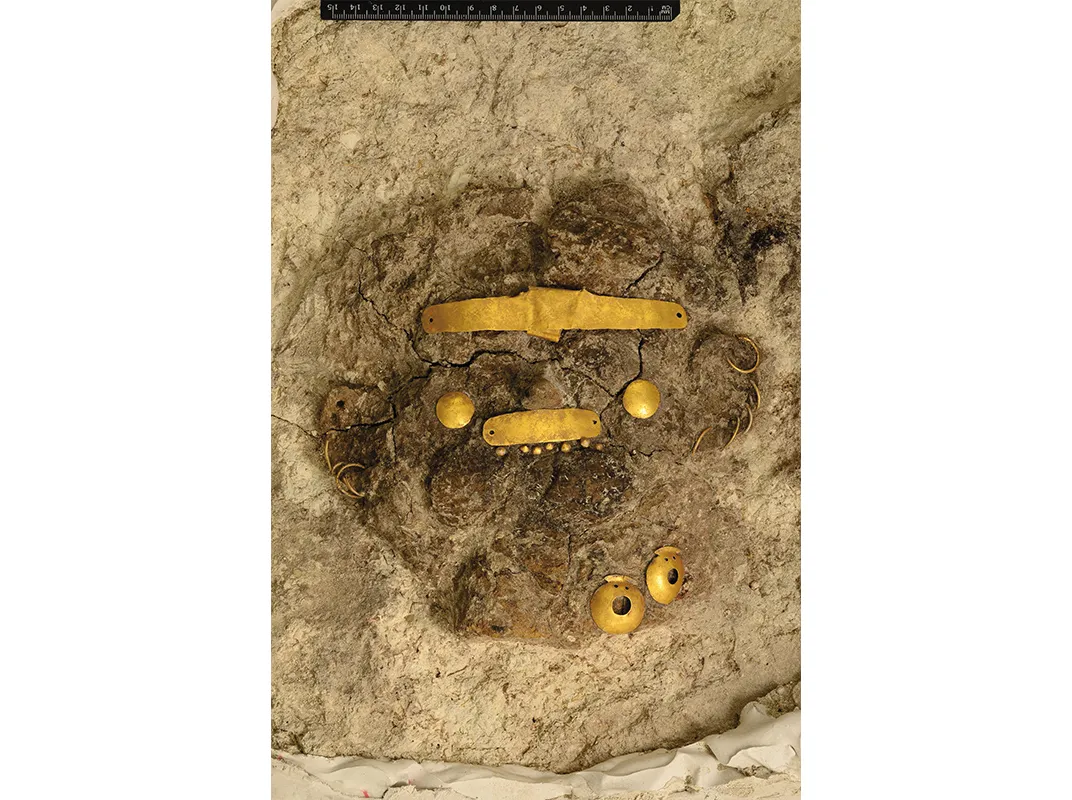

Slavchev leads me to the center of the room, where a grave has been carefully recreated. Though the skeleton inside is plastic, the original gold artifacts have been placed exactly as they were found when archaeologists uncovered the original remains. Laid out on his back, the long-dead man in grave 43 was adorned with gold bangles, necklaces made from gold beads, heavy gold pendants, and delicate, pierced gold disks that once hung from his clothes.

In the museum display, his hands are folded over his chest, clutching a polished axe with a gold-wrapped handle like a scepter; another axe lies just beneath. There’s a flint “sword” 16 inches long at his side and a gold penis sheath lying nearby. “He has everything—armor, weapons, wealth,” Slavchev says, smiling. “Even the penises of these people were gold.”

**********

Since he started working at the museum in 2001, Slavchev has spent much of his time considering the implications of the Varna gold. His long black hair, shot through with gray, is pulled back in a tight ponytail; his office on the top floor of the museum, where he serves as curator of prehistoric archaeology, is painted green and filled with books about the region’s prehistory. A small window lets in a bit of light and the sound of seagulls.

Slavchev tells me that just a few decades ago, most archaeologists thought that the Copper Age people living around the mouth of the Danube organized themselves in very simple, small groups. An influential 1974 book called Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images, by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, went even further. Based on feminine figurines made of bone and clay found in Copper Age settlements along the lower Danube, she argued that the societies of “Old Europe” were run by women. The people of “Old Europe” were “agricultural and sedentary, egalitarian and peaceful,” Gimbutas wrote. Her vision of a prehistoric feminist paradise was compelling, especially to a generation of scholars coming of age in the 1960s and '70s.

Gimbutas thought the Copper Age ended when invaders from the east swept into the region around 4000 b.c. The newcomers were “patriarchal, stratified … mobile, and war oriented”—everything the people of the Copper Age weren’t. They spoke Indo-European, the ancient tongue that forms the basis for English, Gaelic, Russian, and many other languages. The new arrivals put their stamp on Europe, and wiped out the goddess worship of the Copper Age in the process.

Gimbutas was putting the finishing touches on Goddesses and Gods as the first finds from Varna were coming to light. She couldn’t have known that this cemetery deep behind the Iron Curtain would come to challenge her theory.

In hindsight, the evidence is compelling. When I ask Slavchev about the conclusions drawn by Gimbutas, who died in 1994, he shakes his head. “Varna shows something completely different,” he says. “It’s clear the society here was male dominated. The richest graves were male; the chiefs were male. The idea of a woman-dominated society is completely false.”

**********

The Varna find still seems miraculous to those who were part of it. In 1972 Alexander Minchev was just 25, with a freshly minted Ph.D. and a new job at the same museum he works in today as senior staff member and expert in Roman glass. One morning he got a call: A former schoolteacher who had opened a small museum in a nearby village was in possession of some treasure; perhaps someone from Varna would be willing to come take a look?

When the call came in, Minchev recalls, his older colleagues rolled their eyes. Locals were routinely calling about “treasure.” It always turned out to be copper coins they found in their fields, some just a few centuries old. The museum’s storerooms were full of them. Still, Minchev was eager to get out of the office, so he jumped in a jeep with a colleague.

Entering the smaller museum, the two men immediately realized this was no collection of old coins. “When we walked in the room and saw all these gold artifacts on his table, our eyes popped—this was something exceptional,” Minchev says. The retired teacher told them a former student had uncovered the artifacts a few weeks earlier while digging trenches for electrical cables. After fishing a bracelet out of the bucket of his excavator, the young man gathered up a few more pieces. He assumed the jewelry was copper or brass, and tossed it in the box that came with his new work boots, then shoved it under his bed. Gold never crossed his mind. A few weeks went by before he gave the box of jewelry, still covered in dirt, to his old teacher.

Until that morning, all the known gold artifacts from the Copper Age weighed less than a pound—combined. In the shoebox alone, Minchev was holding more than double that. The initial find was 2.2 pounds, in the form of bracelets, a flat, rectangular breastplate, earrings, delicate tubes that might have fit around a scepter’s wooden handle, some rings, and other small trinkets. “We took them in that same shoebox straight back to Varna,” Minchev says.

Within weeks the bewildered backhoe operator was leading a cop, two archaeologists, and his former teacher to a construction site a few hundred yards from Varna’s lake. Though it had been months since the construction worker found the gold, Minchev immediately spotted more glitter peeking out of the loose dirt on the side of the trench.

**********

The hunt was on. “It’s very rare to have just one grave,” Minchev says. “Very soon, we found more. After it was obvious it was a cemetery, a temporary fence was erected. It turned out later it wasn’t big enough [to contain the full circumference of the graveyard].” As winter closed in and the ground froze solid, archaeologists lit fires to keep the work going. In a strange twist, a local prison supplied convict labor to help the archaeologists recover the cemetery’s gold.

Bulgarian archaeologists spent more than 15 years excavating 312 graves. All date to a relatively brief period between 4600 and 4200 b.c.—a pivotal point in human history, when people were just beginning to unravel the secrets of metalworking.

As researchers dug up one new grave after another, a pattern emerged. The riches of Varna’s cemetery weren’t evenly distributed. The majority of the burials contained very little of value: a bead, a flint knife, a bone bracelet at best. One in five contained small gold objects like beads or pendants. Shockingly, just four graves contained three quarters of the cemetery’s gold—the Copper Age’s equivalent of the wealthiest one percent. “The cemetery shows big differences between people, some with lots of grave goods, some with very few,” Slavchev says. “6,500 years ago, people had the same ideas we have today. Here we see the first complex society.”

Varna and its gold quickly became celebrated outside of Bulgaria. The country’s communist leadership was eager to promote the site, and they sent the jewelry on tour to museums around the world.

Bulgarian archaeologists chuckled at the irony. “I joked with a colleague that this cemetery was the first nail in the coffin of communist ideology,” Minchev says. “It showed that even in the 5th century b.c., society was very stratified, with very rich people, a middle class, and mostly people with nothing but a pot or a knife to call their own. It was the opposite of the official ideology.”

**********

A day after meeting Minchev, I head back to the museum. This time, I’m not there to see gold. Instead, Slavchev is waiting outside. His car is in the shop, so we hop in a colleague’s battered silver Mitsubishi SUV. We’re going to see the cemetery itself—or what’s left of it.

As we weave through mid-day traffic on the edge of Varna, through cookie-cutter apartment blocks and post-communist commercial developments, Slavchev explains that a significant chunk of the cemetery—perhaps a third—was never excavated. In 1991, the archaeologist in charge called a halt to the dig. He reasoned that future researchers would have access to better technology and techniques, and he wanted to finish publication of the work already done.

He couldn’t have known that the end of communism would plunge Bulgarian archaeology into a slump that’s lasted more than two decades. Today, Bulgaria is one of the poorest countries in the European Union, and as scientists have struggled to fund legitimate excavations, looters have plundered many of the country’s archaeological treasures and sold them on the international black market. The Varna site has thus far been spared.

After turning off the main road into a bleak industrial park, we pull up next to a nondescript chain-link fence. Slavchev gets out of the car and unlocks a gate. Together we slip into a long, narrow strip of land squeezed between run-down factory buildings and warehouses that tower on all sides.

Locals have turned the fenced area into an informal community garden, with small vegetable plots and ramshackle greenhouses made of plastic sheeting. Where it hasn’t been planted with vegetables, the space is choked with thick underbrush and strewn with trash. A sign written in black marker on a piece of blue plastic reads, “God is watching from above—Don’t steal!”

Twenty-five years after the original excavation was halted, Slavchev is still publishing findings, and hoping eventually to restart the Varna dig and complete the work of his predecessors. One of the questions he’d like to answer: What was it about the Copper Age that encouraged people to create social hierarchies? And why here on the shores of the Black Sea?

**********

Picking his way through the gardens, Slavchev suggests the people who built the Varna cemetery had more on their minds than subsistence. “The whole population was in good health and had a well-balanced diet. These people were not rich or poor in today’s sense. They didn’t go hungry,” he says. “They had reached a moment where they started to think about more than survival.”

Slavchev thinks their minds turned to metal. Sitting by a campfire one night, not long after 5000 b.c., an observant Stone Age farmer must have noticed that certain rocks—green-blue ores we now know as malachite or azurite—melted into shiny beads of copper when they got hot.

Copper could be shaped and worked into tools and decorations in a way that must have seemed otherworldly. Until the invention of metallurgy, all the tools humanity had at its disposal were crafted from stone, wood, bone, antler, or clay. Once they broke, they were useless. Malleable copper, though, could be shaped into weapons, tools, and jewelry over and over again. “If a metal axe is broken, you can melt it down and produce another axe,” says Svend Hansen, the head of the Eurasia department at the German Archaeological Institute. “Metal is never used up. It can be recycled endlessly.” The first metalworkers must have seemed like wizards.

But while stone and bone were widely available—materials anyone could pick up off the ground—malachite, azurite, and gold were all hard to come by. A pound of copper requires mining hundreds of pounds of copper ore; it takes up to ten tons of material to yield an ounce of gold. Mining, smelting, and working metal took special skills and lots of time.

All those man-hours needed to be organized and ordered. That’s where the man in grave 43 and his fellow one-percenters came in. “We come for the very first time to a crucial point in human history—part of society must work with metal, and others must feed them,” Slavchev says. “That separation has to be ordered and regulated, with somebody assigning roles. The person making decisions has to have a lot of power to keep society separated.”

**********

Slavchev and I are soon standing on a slight rise, covered in a thicket of brush and stubby trees. A few rotting sheds are barely visible in the undergrowth. He points to a handful of shallow pits downslope, so covered with weeds I wouldn’t have noticed them without his help. “You’re standing on top of the cemetery,” he says. “That’s where they found the richest graves.” Excavators later piled all the dirt from the graves on the part of the cemetery they hadn’t yet examined, sealing it under 15 feet of soil to wait for better days.

As a cold wind carries the sound of clanging metal from a nearby factory, I ask Slavchev something I’ve been wondering since we met: What happened to the society that once existed here? The golden age entombed in the cemetery was brief, he says. The bones were all buried within a few centuries, between 6,600 and 6,200 years ago.

What happened next is an enduring mystery. All along the lower Danube, settlements and cultures that flourished during the Copper Age come to an abrupt end around 4000 b.c. Suddenly, settlements are abandoned; the people vanish. For six centuries afterwards, the region seems to be empty. “We still have nothing to fill the gap,” he says. “And believe me, we’ve looked.”

For decades, scholars assumed the sudden abandonment was the result of an invasion by the mounted Indo-European warriors Gimbutas had written about, rampaging through the region. But there are no signs of battle or violence, no burned villages or skeletons with signs of slaughter.

More recently, researchers have begun considering another possibility—climate change. The collapse of the Copper Age coincides with a warming world, with larger swings in temperatures and rainfall. The villages that produced the gold found here are now underwater: The Black Sea was as much as 25 feet lower than it is today.

From the top of the cemetery, it’s just possible to peek over the factory fences and see the lake that covered the villages. All the gold in the world—or at least most of it—couldn’t save them. “Perhaps their fields became swamps,” Slavchev says, closing and locking the gate behind us. “With the changes in climate, maybe people had to change their way of life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)