A Tour of the World’s Most Spectacular Ceilings

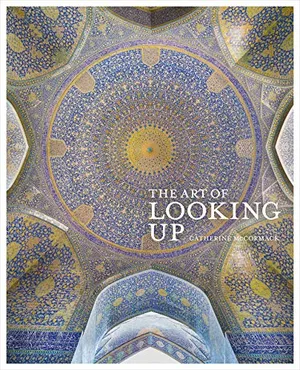

In her new book ‘The Art of Looking Up,’ Catherine McCormack captures stunning ceilings around the globe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/ae/a3aec59a-228c-4d3d-9494-2b030f36e884/lead_image.jpg)

In her new book The Art of Looking Up, art historian Catherine McCormack asks readers the thought-provoking question: “Why do we look up?” It could be that we’re looking for guidance or maybe it’s because we’re intrigued by what hovers above our normal perception of the universe. Either way, she makes the case that craning your neck and examining what lies overhead gives you a new appreciation of your surroundings.

With that idea in mind, McCormack set out to discover some of the most spectacular ceilings found inside buildings around the world—from a mosque in Iran to the soaring nave of a cathedral in Spain. In her new book, to be released October 29 by White Lion Publishing, she captures the history of 4o ceilings while outlining details that might normally go unnoticed—like a ceiling comprised of millions of scarab beetles in Belgium and another one in Switzerland dripping in 35 tons of paint.

Here are eight of our favorites:

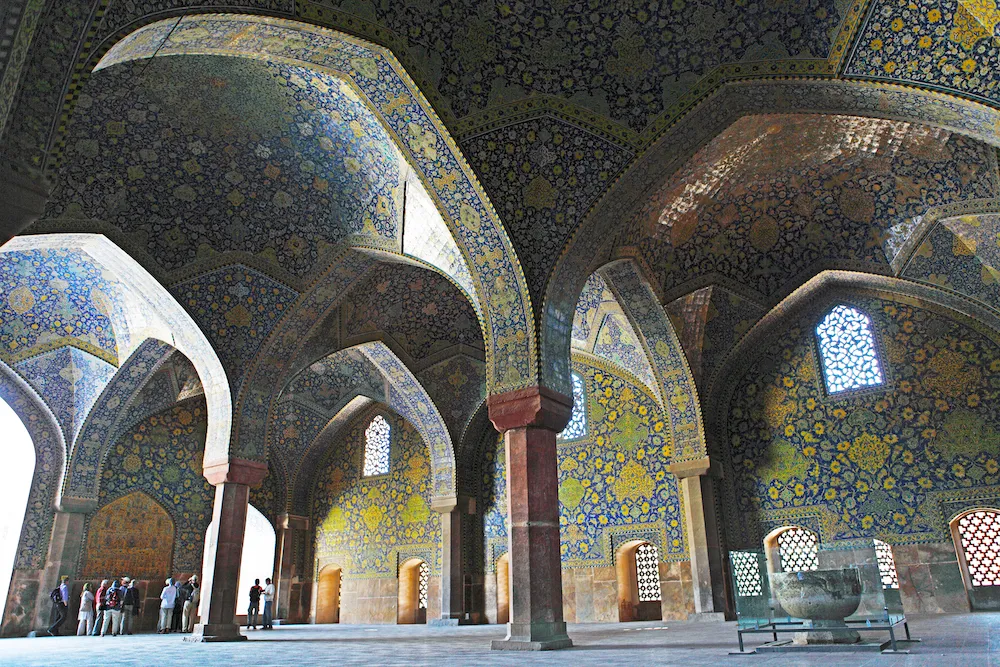

Imam Mosque, Isfahan, Iran

Construction of the Imam Mosque took place between 1661 and 1666 as part of an aggressive construction campaign led by Shah ‘Abbas I to embellish the new Iranian capital of Isafan, and not a single square inch was spared when it came to adornment. With nearly half a million colored geometric tiles, workers created intricate patterns that creep up the mosque’s walls and onto the building’s domed ceiling. Interestingly, the motifs do not contain any sort of recognizable objects or symbolism, such as people or animals. McCormack surmises, “These motifs strike a more metaphysical note and operate as elements of color and form. When repeated, as they are here in seemingly infinite patterns, they evoke something akin to a flow of pure perception that lifts the viewer out of the ordered and finite world to experience something transcendental. It is through this silent theology of color, light, repetition and order that God appears, therefore, and not through a figurative image.”

Even now, five centuries later, the mosque’s architectural complexity continues to be as awe inspiring as it was when the final tile was laid. In fact, it’s featured on Iran’s 20,000 rial banknote.

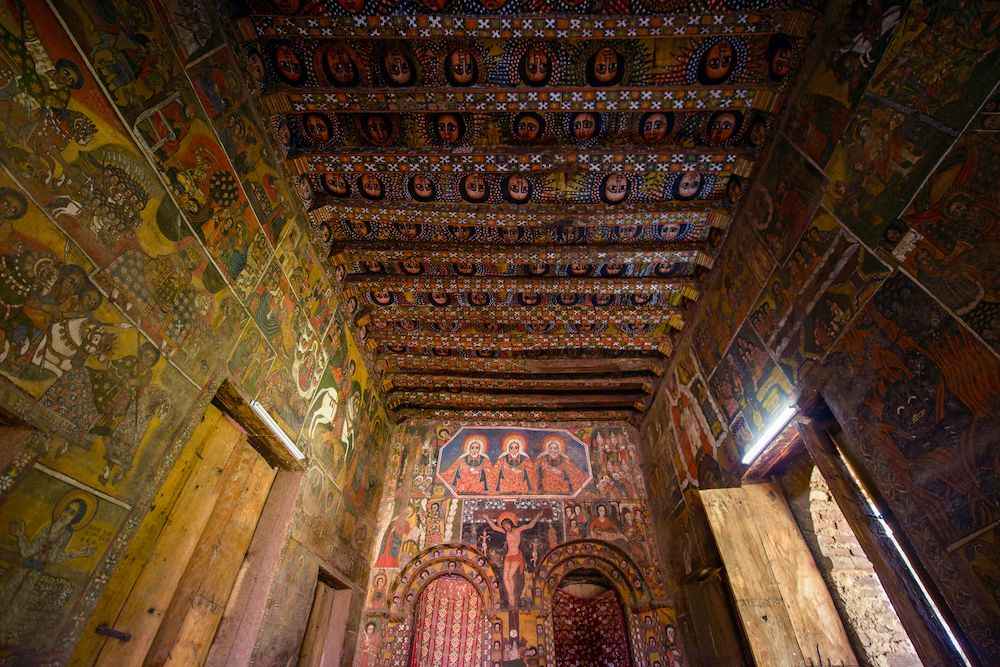

Debre Berhan Selassie Church, Gondar, Ethiopia

The ceiling of Debre Berhan Selassie Church in Ethiopia is comprised of row upon row of angels—135 in total—looking down from heaven above onto a series of biblical scenes. These scenes include images of the Holy Trinity and symbols of the four writers of the gospel in the form of a lion (Mark), an eagle (John), a bull (Luke) and an angel (Matthew). Over the centuries, many people believe that it’s the watchful gaze of these disembodied cherubs that saved the 18th century church from complete destruction. In 1888, the Mahdists of the Sudan attacked the city of Gondar, burning down every single church in the city, sparing only Debre Berhan Selassie. According to legend, many believe that it was the frescoes of angels that provided the church with protection, which McCormack says isn’t too surprising: “It points to a human belief in the real power of images—one we have mostly forgotten now that we encounter them mostly in museums and galleries, in this case a belief that images of religious beings had apotropaic power.”

Palais Garnier, Paris, France

When France's minister of cultural affairs André Malraux decided that the ceiling of the Palais Garnier, home of the city’s ballet and opera, needed a facelift to better meet the aesthetic of a 1960s audience, he tapped Russian painter Marc Chagall for the job. Chagall supposedly worked all hours of the day, forgoing food and drink and listening to Mozart. He was so vigorous in his work that he would break a new paintbrush every 15 minutes or so. Inspired by the Austrian composer, Chagall created a masterpiece on canvas evoking a flower comprised of five different colored petals, with each petal representing two composers in the Paris Opera’s repertoire.

“The white petal honors the composers Rameau and Debussy and commemorates the creation of the work,” McCormack says. “A portrait of Chagall’s patron Malraux looking from the window doubles as an episode from Debussy’s ballet Pelléas and Mélisande. This also marks one of Chagall’s self-conscious references to the art of the past, in particular, the tradition of Renaissance painting, in which portraits of patrons are often featured. A voluptuous nude leans on to the green petal, which is devoted to Wagner and his tragic lovers Tristan and Isolde, and Berlioz’s choral symphony of Roméo et Juliette.”

Metro Stations, Stockholm, Sweden

Normally you have to look up in the sky to spot a rainbow, but in Stockholm, Sweden, one of the most striking rainbows can be found underground. In the labyrinth of tunnels that make up the city’s metro system, one station stands out in particular: Stadion. The station was constructed prior to the 1912 Stockholm Olympics and served as the gateway to Stockholm Olympic Stadium. The station’s five-colored rainbow refers to the five interlocking Olympic rings, but over the years the brightly colored mural has become a popular emblem for members of the LGBTQ community.

All told, about 100 stations serving Stockholm are decorated with colorful murals, making the metro system one of the most striking of any in the world. In her book, McCormack writes, “The project, which dates back to the 1950s, was motivated by the realization that the train stations—often dreary, functional spaces—could serve a cultural purpose, with artists crafting a more engaging experience for city-dwellers as they commuted across the city. So, replacing cavernous exposed rock and bleaching strip lighting, a series of murals and objects provide the one hundred or so stations in the network with a different aesthetic experience.”

Sagrada Família, Barcelona, Spain

Soaring an impressive 145 feet in height, the nave of Sagrada Família, a Gothic cathedral in Barcelona, Spain, is the work of Antoni Guadí. Inspired by the mathematical laws found within the natural world, the Catalan architect incorporated, as McCormack describes in her book, “the hyperbolic paraboloids of tree trunks and their branches, along with conoids, fractals and spirals” into the space. He believed that God was the “supreme architect of nature” and combined that thinking with new ideas such as Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity, which introduced a new perspective on the way space and time could be perceived.

McCormack compares entering the cathedral to being in nature. “Everything you look at is a mirror of the shapes and patterns found in nature,” she says. “Stepping inside the building is like entering an enchanted forest, as twisting helicoidal columns seemingly grow out of the ground, splitting into branches that support a weighty vaulted ceiling of tessellated sunflower shapes, while a rainbow haze filters through the colored glass windows. Like giant beanstalks these columns form a solid vertical bridge between the mortal world at ground level and the celestial space above, and seem to suggest that heaven has its roots deep inside the Earth.”

Royal Palace of Brussels, Belgium

Upon first glimpse, the iridescent hues that make up the barrel-vaulted ceiling inside the Royal Palace could be attributed to the work of a particularly crafty painter. But upon closer inspection, the lustrous space is really comprised of 1.6 million scarab beetle wing casings. The ceiling is the work of Dutch artist Jan Fabre, who is known for his usage of unconventional materials in his artwork—in this case insects. Over the course of four months, Fabre and his team collected discarded wing casings from restaurants in Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, where beetles are considered a delicacy. He then went about the arduous tasks of creating a mosaic on the ceiling that shape shifts into natural forms, such as the “legs of a giraffe, the wings of birds and the eyes of salamanders,” writes McCormack in her book.

“[Fabre] reminds us that beauty and power are not always comfortable,” McCormack says. “Moreover, he turned something that is normally wasted—the insect is eaten as a delicacy and wing cases discarded—into something symbolic of power wealth and status.”

Dalí Theater-Museum, Catalonia, Spain

Staring up at the Dalí Theater-Museum’s ceiling in Catalonia, you are confronted with two massive sets of feet rising into the heavens. The imagination-capturing scene is the work of Salvador Dalí, and it is shrouded in the surrealist painter's signature warped clocks. “Dali draws on numerous references to art history in this ceiling—and this reference is to the way in which the departing body of Christ was depicted in Christian iconography when he ascended into heaven,” McCormack says. “It is a startling point of view because we don't always consider this surface of the body as it’s normally hidden from sight, and not really considered at all.”

Called Palace of the Wind, the massive piece spreads across five giant canvases, which Dalí painted at his studio in Port Lligat, and is inspired by the poem L’Empordà by Catalan poet Joan Maragall.

United Nations Office, Geneva, Switzerland

Dripping in 35 tons of paint, the ceiling inside the United Nations Office in Geneva calls to mind stalactites hanging in a cave. To make the impressive piece of art, artist Miquel Barceló collected rocks and fragments of earth from around the globe and incorporated them into handmade pigments as a way to “come together in a miasmic polychromatic flow irrespective of the borders, racial differences or colors of their origins, to express the utopian political ideal of harmonious international relations.” Barceló was inspired by a mirage he witnessed in Africa’s Sahel desert, which he described as “a vision of the world flowing drop by drop towards the sky.” Despite his creative attempt at unification, many people balked at the $23-million Euro price tag to create the piece. “The cost was controversial as some people might think that the United Nations should spend the cost of designing a new ceiling for a meeting room on other initiatives and don't see art as a worthy medium to encourage international human rights dialogue,” McCormack says. “I suppose it goes back to the belief in the power of images again.”

The Art of Looking Up

The Art of Looking Up surveys 40 spectacular ceilings around the globe that have been graced by the brushes of great artists including Michelangelo, Marc Chagall, and Cy Twombly.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.