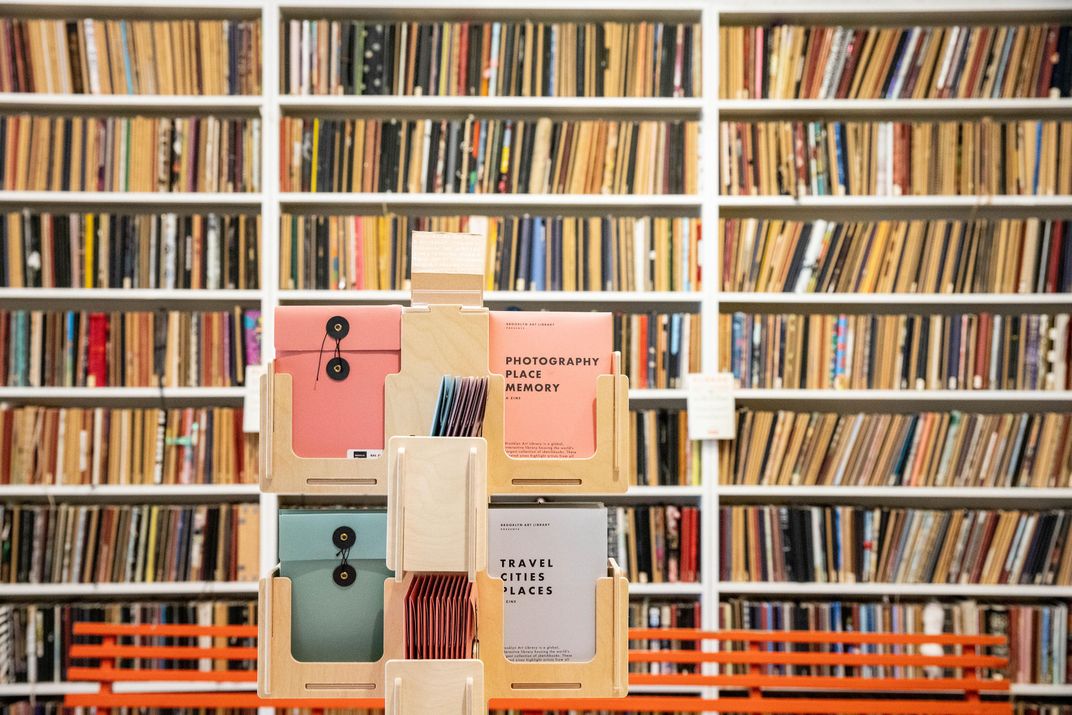

This Library in Brooklyn Is Home to the World’s Largest Sketchbook Collection

With more than 50,000 sketchbooks, the Brooklyn Art Library in Williamsburg is still accepting submissions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/df/9adf6f7a-1275-4787-9063-af329d6a877e/brooklyn_art_library.jpg)

Allie Cassidy, a 29-year-old from Illinois, is working on a sketchbook. Its pages are full of “metaphorical ghosts,” as she puts it, or the people and places that have influenced her life and still stick with her today.

“We are all influenced every day by the people we take an interest in, good or bad, dead or alive, real or fictional,” she says. “We think about what they would say or do, what wisdom they would have to impart, or how we can be different from them. We also tend to leave pieces of ourselves in places that mean or once meant a lot. I metaphorically sat with these people in these places for most of 2020, since I literally couldn’t sit anywhere else with anyone else. Now I’m going to bring it all out into the world to share with others.”

From front to back, Cassidy's sketchbook is decorated with illustrations of Italian poet Dante Alighieri, Addams Family matriarch Morticia Addams, Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, and little aliens she used to draw as a child. Adorning the pages are important places to her: an apartment in Chicago, a make-believe house, a home in Florence. When she’s completely filled her book, Cassidy will submit it to the Brooklyn Art Library to be cataloged in the Sketchbook Project, a program that’s celebrating its 15th anniversary this year.

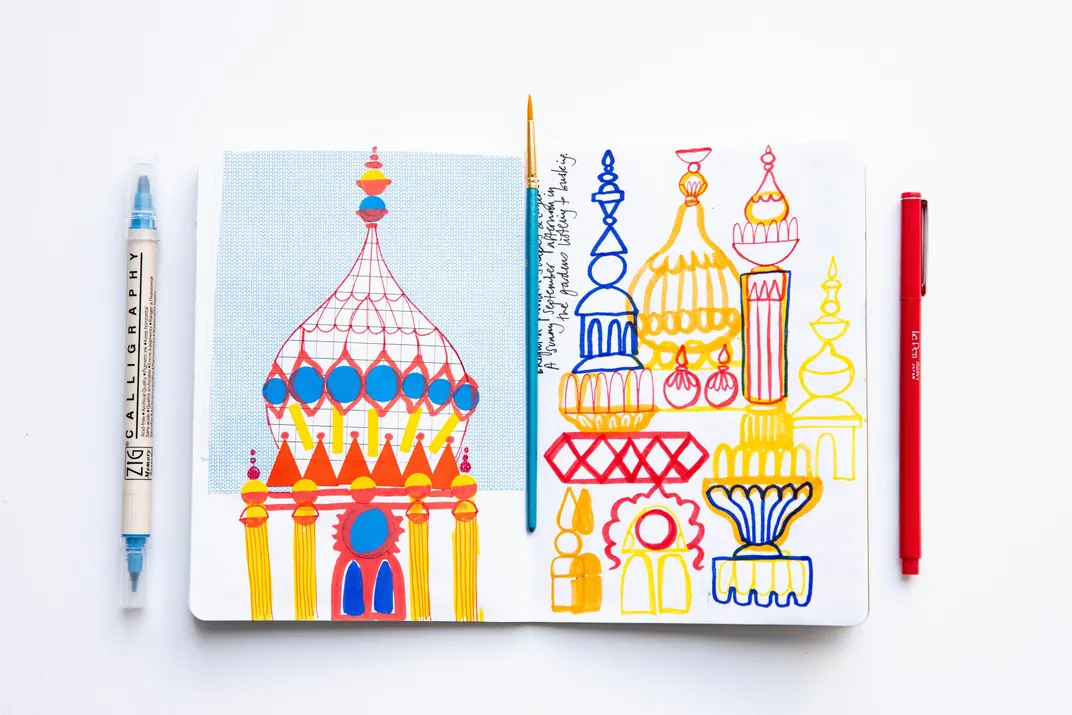

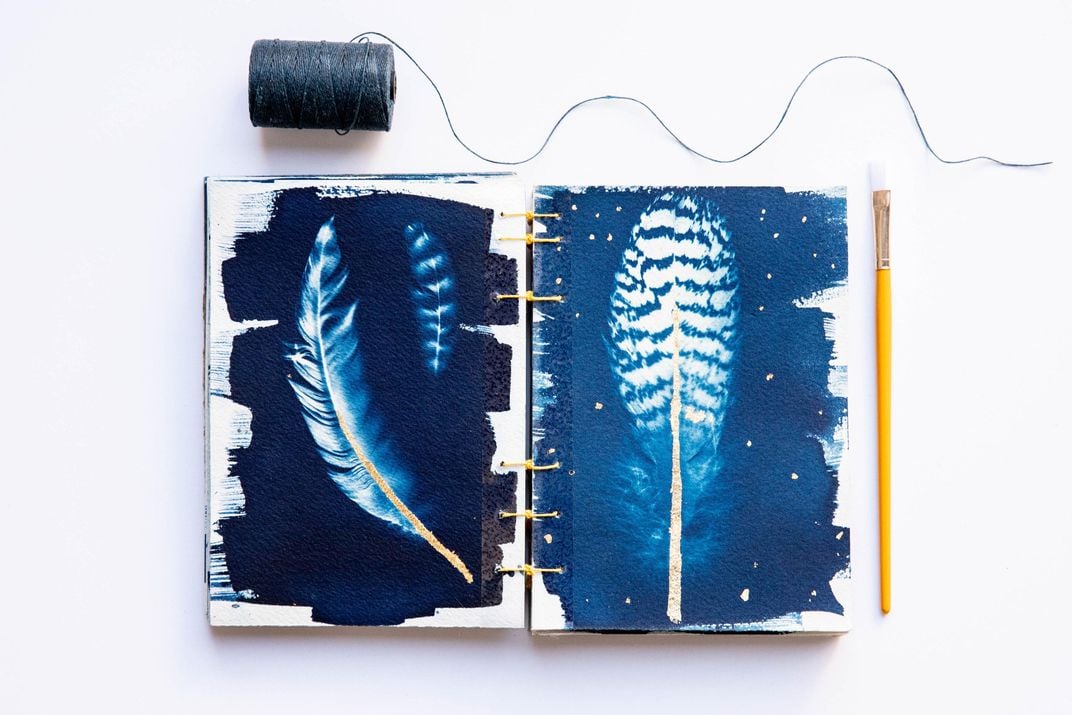

The Sketchbook Project works like this: people interested in submitting a sketchbook order a blank one from the website. When it arrives, they fill it with art, writing, decoupage, pop-ups, or anything else that fits their chosen style or theme. Some of the more unique sketchbooks have included embroidered pages and back covers altered to unfold into long maps and drawings. One sketchbook opens into a puzzle; another is cut in the shape of a sandwich. Participants have up to eight months to send the completed sketchbook back, at which point it is cataloged and put into the permanent collection. Sketchbooks are rarely rejected after they’re submitted—it would have to include something extremely offensive, possibly cause damage to other books in the collection, or contain something unsanitary. But if the library is considering rejecting one, the staff has a conversation with the artist to gain more context around the artwork. A standard sketchbook costs $30, and one that’s digitized and put online costs $65.

Those interested in browsing the collection can stop by the Brooklyn Art Library, a 2,500-square-foot brick two-story building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn (open by appointment only during the Covid-19 pandemic), or visit the website, search for books by artist or keyword, and peruse a stranger’s artwork. Whenever someone checks out a book digitally, the artist is notified. Each sketchbook receives a unique seven-digit barcode that allows the team to catalog the book, organizing them by year received and theme (you receive a list of themes to choose from when you order your book). Occasionally books following those themes are showcased either in the library, at a satellite exhibit, or in the library's bookmobile.

When founder Steven Peterman started the project in Atlanta in 2006, he wasn’t sure where it would take him. Three years later, he moved to New York and found a rental in Brooklyn to house the permanent sketchbook collection, which now has more than 50,000 sketchbooks from some 130 countries. In 2020, the Brooklyn Art Library officially became a nonprofit.

“It was a very literal thing in the beginning,” Peterman says. “We were very much like, what could someone fill up a sketchbook with? As time has gone by, it’s really taken on its own story. We are a global community. We have our 15-year snapshot of what we have been collecting. I think the biggest shift now has been the mentality of changing this active project to a project that inspires people in other ways.”

To that end, Peterman and the rest of the six-person Sketchbook Project team and five-person Board of Directors are launching initiatives to expand access to the books and to inspire participants to spread the word about their work. In February, they launched “The Brooklyn Art Library Podcast,” where Peterman and associate creative director Autumn Farina discuss the inspiration behind sketchbooks with the artists who created them. One artist, Linda Sorrone Rolon, spoke about using her sketchbook as a therapeutic outlet for the anger she felt after Hurricane Sandy destroyed her home in Brooklyn. She hadn’t planned to send it back, but when Peterman, who had met her a few years prior and knew she was working on a sketchbook, contacted her about doing a Mother’s Day interview for a blog post the library was working on about artists with children, she handed the book over when he arrived at her house.

“It was such an important moment for her to let go of all these feelings,” Peterman says. “I think that sort of thing is so rampant in our collection. There’s something really important about doing this and sending it away and having it live in another place. It teaches you about letting your work go and about being a part of something larger than yourself, which I think is important right now.”

Michelle Moseley, co-director of the Material Culture and Public Humanities masters program at Virginia Tech's School of Visual Arts, notes that along those lines, the sketchbooks she recently browsed online were themed around the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It provides an of-the-moment snapshot of the way people are thinking and feeling about Covid,” she says. “That’s a critical archive. It’s not an academic source; it’s not a more elite or rarified source. These are just people expressing their thoughts and feelings about an unprecedented time in world history, and that in itself is a really valuable historical marker.”

Emergency room nurse Erin Kostner agrees. She isn't quite sure what will be in her sketchbook yet, but promises it will be colorful and bold. She's in the process right now of rebinding the book to completely transform its appearance.

“[The Sketchbook Project] allows anyone to be an artist,” Kostner says. “Deep down, I believe everyone is an artist. Some people are lucky enough to have found their craft while others just haven't found their medium, yet. This makes art human and shares our joined experience in a public place.” She feels art has been trending toward big interactive displays of “all things happy” that, while fun, risk turning into “superficial selfie-paloozas,” as she puts it. “[The Sketchbook Project] beckons art lovers to a more quiet, private experience,” she adds. “Libraries and museums have always been places of great magic and mystery to me. The Sketchbook Project ties the magic of both places into one beautiful, honest project. Here we will see not just the big, bright, and happy, but a rich tapestry of human emotion and experience.”

In addition to the podcast, Peterman and the team are compiling anthologies to sell that feature multiple artists from the collection. They’re also making tweaks to the project that will allow for parts of the physical and digital collection to be displayed at other spaces for both short-term and long-term exhibits.

“We really want to make the collection more accessible,” Peterman says. “Not everyone can come to New York. It really is about getting the collection to where people are and making it more accessible, whether it’s through the internet or other pop-up exhibitions. I love the idea that there are all of these people that have come together in this single format to create this crazy legacy. Who knows what will happen and what it’ll become?”

In the visual art world, The Sketchbook Project is fairly unique. But several writing projects seem similar in nature. Libraries around the world, for example, are running Covid Diaries projects, where you can submit a snapshot of your life during the pandemic through various means like an audio file or a written piece. And the Great Diary Project, based in London, collects donated diaries and journals from anyone who wants to submit them.

“The idea of this being captured in a material archive is really a critical thing,” Moseley says. “It’s another avenue for people to creatively express themselves, and that’s something we really need right now.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)