The Pygmies’ Plight

A correspondent who chronicled their lives in central African rain forests returns a decade later and is shocked by what he finds

Some 50 Pygmies of the Baka clan lead me single file through a steaming rain forest in Cameroon. Scrambling across tree trunks over streams, we hack through heavy undergrowth with machetes and cut away vinelike lianas hanging like curtains in our path. After two hours, we reach a small clearing beneath a hardwood tree canopy that almost blots out the sky.

For thousands of years Pygmies have lived in harmony with equatorial Africa's magnificent jungles. They inhabit a narrow band of tropical rain forest about four degrees above and four degrees below the Equator, stretching from Cameroon's Atlantic coast eastward to Lake Victoria in Uganda. With about 250,000 of them remaining, Pygmies are the largest group of hunter-gatherers left on earth. But they are under serious threat.

Over the past decade, I've visited Pygmy clans in several Congo Basin countries, witnessing the destruction of their traditional lifestyle by the Bantu, as taller Africans are widely known. On this trip, this past February, my companion is Manfred Mesumbe, a Cameroonian anthropologist and expert on Pygmy culture. "The Bantu governments have forced them to stop living in the rain forests, their culture's bedrock," he tells me. "Within a generation many of their unique traditional ways will be gone forever."

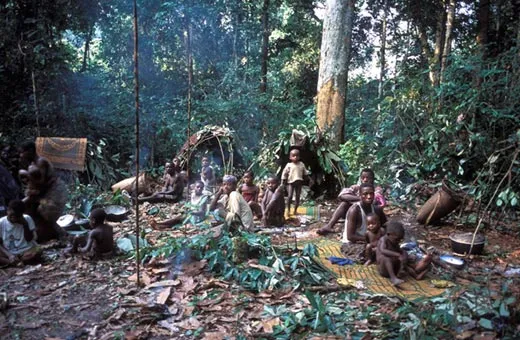

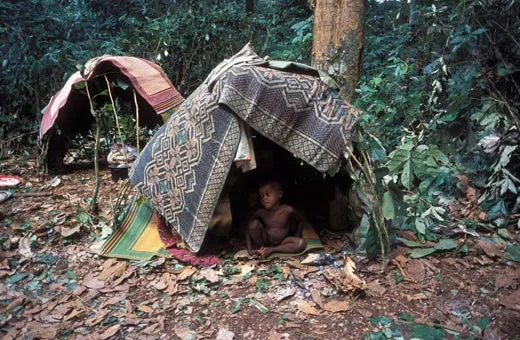

The Baka clan members begin putting up beehive-shaped huts in the clearing, where we will spend the next few days. They chop saplings from among the trees and thrust the ends into the ground, bending them to form the frame of each hut. Then they weave bundles of green leaves into latticework to create a rainproof skin. None of the men stands higher than my shoulder (I'm 5-foot-7), and the women are smaller. As the Baka bring firewood to the camp, Mesumbe and I put up our small tent. Suddenly the Pygmies stir.

Three scowling Bantus brandishing machetes stride into the clearing. I fear that they're bandits, common in this lawless place. I'm carrying my money in a bag strung around my neck, and news of strangers travels fast among the Bantu here. Mesumbe points to one of them, a stocky man with an angry look, and in a low voice tells me he is Joseph Bikono, chief of the Bantu village near where the government has forced the Pygmies to live by the roadside.

Bikono glares at me and then at the Pygmies. "Who gave you permission to leave your village?" he demands in French, which Mesumbe translates. "You Pygmies belong to me, you know that, and you must always do what I say, not what you want. I own you. Don't ever forget it."

Most of the Pygmies bow their heads, but one young man steps forward. It's Jeantie Mutulu, one of the few Baka Pygmies who have gone to high school. Mutulu tells Bikono that the Baka have always obeyed him and have always left the forest for the village when he told them to do so. "But not now," Mutulu announces. "Not ever again. From now on, we'll do what we want."

About half the Pygmies begin shouting at Bikono, but the other half remain silent. Bikono glowers at me. "You, le blanc," he yells, meaning‚ "the white." "Get out of the forest now."

The earliest known reference to a Pygmy—a "dancing dwarf of the god from the land of spirits"—is found in a letter written around 2276 B.C. by Pharaoh Pepi II to the leader of an Egyptian trade expedition up the Nile. In the Iliad, Homer invoked mythical warfare between Pygmies and a flock of cranes to describe the intensity of a charge by the Trojan army. In the fifth century B.C., the Greek historian Herodotus wrote of a Persian explorer who saw "dwarfish people, who used clothing made from the palm tree" at a spot along the West African coast.

More than two millennia passed before the French-American explorer Paul du Chaillu published the first modern account of Pygmies. "[T]heir eyes had an untameable wildness about them that struck me as very remarkable," he wrote in 1867. In In Darkest Africa, published in 1890, the explorer Henry Stanley wrote of meeting a Pygmy couple ("In him was a mimicked dignity, as of Adam; in her the womanliness of a miniature Eve"). In 1904, several Pygmies were brought to live in the anthropology exhibit at the St. Louis World's Fair. Two years later, a Congo Pygmy named Ota Benga was housed temporarily at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City—and then exhibited, briefly and controversially, at the Bronx Zoo.

Just last year, the Congo Republic organized a festival of pan-African music in the capital, Brazzaville. Other participants were put up in the city's hotels, but the organizers housed the 22 Pygmy performers in tents at the local zoo.

The word "Pygmy" comes from the Greek for "dwarfish," but Pygmies differ from dwarfs in that their limbs are conventionally proportioned. Beginning in 1967, an Italian geneticist, Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, spent five winters measuring Pygmies in equatorial Africa. He found those in the Ituri forest, in Congo, to be the smallest, with men averaging 4 feet 9 inches in height and women about three inches less. Researchers are trying to determine why Pygmies have evolved to be so diminutive.

I first encountered Pygmies a decade ago, when I visited the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve in the Central African Republic, an impoverished nation in the Congo Basin, on assignment for Reader's Digest's international editions. The park lies about 200 miles southwest of the national capital, Bangui, along a dirt road hacked through the jungle. In good weather, the journey from Bangui takes 15 hours. When the rains come, it can take days.

We arrived at a village called Mossapola—20 beehive huts—shortly before dawn. Pygmy women in tattered sarongs squatted around several fires as they warmed water and cooked cassava. Most of the men were uncoiling large nets near the huts. About 100 Pygmies lived there.

Through William Bienvenu, my Bantu translator at the time, one of the Dzanga-Sangha Pygmies introduced himself as Wasse. When the translator told me Wasse was the greatest hunter in the Bayaka clan, his broad face broke into a smile. A woman walked down the slope and stood by him, and Wasse introduced her as his wife, Jandu. Like most Bayaka women, her front upper teeth had been carefully chipped (with a machete, my translator said) into points. "It makes me look beautiful for Wasse," Jandu explained.

Wasse had a coiled hunting net slung over his shoulder. He tugged at it, as if to get my attention. "We've talked enough," he said. "It's time to hunt."

A dozen Pygmy men and women bearing hunting nets piled into and on top of my Land Rover. About ten miles along a jungle track, Wasse ordered the driver to turn into the dense undergrowth. The Pygmies began shouting and chanting.

In a little while, we left the vehicle in search of the Pygmies' favorite food, mboloko, a small forest antelope also known as blue duiker. High overhead, chimpanzees scrambled from tree to tree, almost hidden in the foliage. As we climbed a slope thick with trees, Wasse raised an arm to signal a halt. Without a word the hunters swiftly set six vine nets into a semicircle across the hillside. Wooden toggles hooked onto saplings held the nets firm.

The Bayaka disappeared up the slope, and a few minutes later the jungle erupted in whoops, cries and yodels as they charged back down. A fleeing porcupine hurtled into one of the nets, and in a flash Jandu whacked it on the head with the blunt edge of a machete. Next a net stopped a terrified duiker, which Wasse stabbed with a shortened spear.

After about an hour, the Bayaka emerged carrying three duiker and the porcupine. Wasse said he sometimes hunted monkeys with a bow and poison arrows, but, he went on, "I prefer to hunt with Jandu and my friends." They would share the meat. When we reached the Land Rover, Jandu held up a duiker carcass and burst into song. The other women joined in, accompanying their singing with frenetic hand-clapping. The sound was extraordinary, a high-pitched medley of warbling and yodeling, each woman drifting in and out of the melody for the half-hour it took to return to Mossapola.

"Bayaka music is one of the hidden glories of mankind," Louis Sarno, an American musicologist who has lived with the Bayaka for more than a decade, would tell me later. "It's a very sophisticated form of full, rich-voiced singing based on pentatonic five-part harmonies. But you'd expect that, because music is at the heart of Bayaka life."

Drumming propelled their worship of the much-loved Ejengi, the most powerful of the forest spirits—good and evil—known as mokoondi. One day Wasse told me that the great spirit wanted to meet me, and so I joined more than a hundred Mossapola Pygmies as they gathered soon after dusk, beating drums and chanting. Suddenly there was a hush, and all eyes turned to the jungle. Emerging from the shadows were half a dozen Pygmy men accompanying a creature swathed from top to bottom in strips of russet-hued raffia. It had no features, no limbs, no face. "It's Ejengi," said Wasse, his voice trembling.

At first I was sure it was a Pygmy camouflaged in foliage, but as Ejengi glided across the darkened clearing, the drums beat louder and faster, and as the Pygmies' chanting grew more frenzied, I began to doubt my own eyes. As the spirit began to dance, its dense cloak rippled like water over rocks. The spirit was speechless, but its wishes were communicated by attendants. "Ejengi wants to know why you've come here," shouted a squat man well short of five feet. With Bienvenu translating, I answered that I had come to meet the great spirit.

Apparently persuaded that I was no threat, Ejengi began dancing again, flopping to the ground in a pile of raffia, then leaping up. The music thudded as the chanting gripped my mind, and I spun to the pounding rhythm, unaware of time's passing. As I left for my lodgings, at about 2 a.m., the chanting drifted into the trees until it melted into the sounds of the rain forest night.

I left Dzanga-Sangha reluctantly, happy that I'd glimpsed the Pygmies' way of life but wondering what the future held for them.

Upon my return to the Central African Republic six years later, I found that Bayaka culture had collapsed. Wasse and many of his friends had clearly become alcoholics, drinking a rotgut wine made from fermented palm sap. Outside their hut, Jandu sat with her three children, their stomachs bloated from malnutrition. A local doctor would tell me that Pygmy children typically suffer from many ailments, most commonly ear and chest infections caused by lack of protein. At Mossapola I saw many kids trying to walk on the edges of their soles or heels—trying not to put pressure on spots where chiggers, tiny bug larvae that thrive in the loose soil, had attached themselves.

Wasse gave me a wistful welcoming smile and then suggested we go to the nearby village of Bayanga for palm wine. It was midmorning. At the local bar, a tumbledown shack, several half-sozzled Bantu and Pygmy men greeted him warmly. When I asked when we could go hunting, Wasse sheepishly confided that he had sold his net and bow and arrows long ago. Many Pygmy men there had done the same to get money for palm wine, Bienvenu, my translator again on this trip, would tell me later.

So how do the children get meat to eat? Bienvenu shrugged. "They rarely get to eat meat anymore," he said. "Wasse and Jandu earn a little money from odd jobs, but he mostly spends it on palm wine." The family's daily meals consist mostly of cassava root, which fills the stomach but doesn't provide protein.

When I asked Wasse why he stopped hunting, he shrugged. "When you were here before, the jungle was full of animals," he said. "But the Bantu poachers have plundered the jungle."

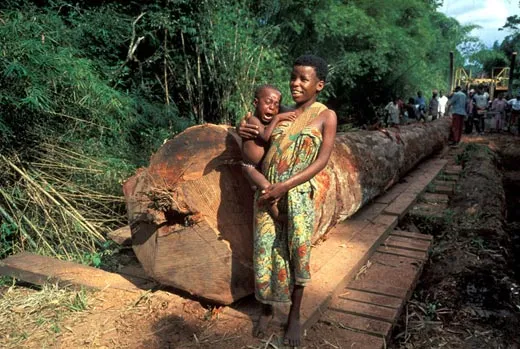

Pygmy populations across the Congo Basin suffer "appalling socio-economic conditions and the lack of civil and land rights," according to a recent study conducted for the London-based Rainforest Foundation. They have been pushed from their forests and forced into settlements on Bantu lands, the study says, by eviction from newly established national parks and other protected areas, extensive logging in Cameroon and Congo and continued warfare between government and rebel troops in Congo.

Time and again on this visit, I encountered tales of Bantu prejudice against Pygmies, even among the educated. On my first trip to Mossapola, I had asked Bienvenu if he'd marry a Pygmy woman. "Never," he growled. "I'm not so stupid. They are bambinga, not truly humans, they have no civilization."

This belief that Pygmies are less than human is common across equatorial Africa. They "are marginalized by the Bantu," says David Greer, an American primatologist who lived with Pygmies in the Central Africa Republic for nearly a decade. "All the serious village or city leaders are Bantu, and they usually side with other Bantu" in any dispute involving Pygmies.

The Ruwenzori Mountains, also known as the Mountains of the Moon, straddle the Equator to form part of the border between Uganda and Congo. The forests here have long been home to the Batwa, at 80,000 the largest Pygmy tribe; they are also found in Rwanda and Burundi. I visited them this past February.

On the Uganda side of the border, our Land Cruiser trundled over a dirt road high along the flanks of the steep foothills. The hills have long been stripped of trees, but their slopes plunge to verdant valleys—a vast rain forest set aside as a national park.

Several hours from Fort Portal, the nearest large population center, we stopped at a Bantu town swarming with people. It was market day, and scores of vendors had spread out their wares—goat carcasses, sarongs, soap, mirrors, scissors. My guide, John Nantume, pointed to a huddle of mud huts about 50 yards away and identified it as the local Pygmy village.

I was surprised that the Pygmies were living so close to their traditional enemies. Mubiru Vincent, of Rural Welfare Improvement for Development, a nongovernmental organization that promotes Batwa welfare, later explained that this group's displacement from the rain forest began in 1993, because of warfare between the Ugandan Army and a rebel group. His organization is now trying to resettle some of the Batwa on land they can farm.

About 30 Batwa sat dull-eyed outside their huts. The smallest adult Pygmy I'd ever seen strode toward me, introduced himself as Nzito and told me that he was "king of the Pygmies here." This, too, surprised me; traditionally, Pygmy households are autonomous, though they cooperate on endeavors such as hunts. (Greer later said that villages usually must coerce individuals into leadership roles.)

Nzito said his people had lived in the rain forest until 1993, when Ugandan "President Museveni forced us from our forests and never gave us compensation or new land. He made us live next to the Bantu on borrowed land."

His clan looked well fed, and Nzito said they regularly eat pork, fish and beef purchased from the nearby market. When I asked how they earn money, he led me to a field behind the huts. It was packed with scores of what looked like marijuana plants. "We use it ourselves and sell it to the Bantu," Nzito said.

The sale and use of marijuana in Uganda is punishable with stiff prison terms, and yet "the police never bother us," Nzito said. "We do what we want without their interference. I think they're afraid we'll cast magic spells on them."

Government officials rarely bring charges against the Batwa generally "because they say they're not like other people and so they're not subject to the law," Penninah Zaninka of the United Organisation for Batwa Development in Uganda, another nongovernmental group, told me later in a meeting in Kampala, the national capital. However, Mubiru Vincent said his group is working to prevent marijuana cultivation.

Because national parks were established in the forests where Nzito and his people used to reside, they cannot live there. "We're training the Batwa how to involve themselves in the nation's political and socioeconomic affairs," Zaninka said, "and basic matters such as hygiene, nutrition, how to get ID cards, grow crops, vote, cook Bantu food, save money and for their children to go to school."

In other words, to become little Bantu, I suggested. Zaninka nodded. "Yes, it's terrible," she said, "but it's the only way they can survive."

The Pygmies also face diseases ranging from malaria and cholera to Ebola, the often fatal virus that causes uncontrollable bleeding from every orifice. While I was with the Batwa, an outbreak of the disease in nearby villages killed more than three dozen people. When I asked Nzito if he knew that people nearby were dying of Ebola, he shook his head. "What's Ebola?" he asked.

Cameroon is home to about 40,000 Baka Pygmies, or about one-fifth of Africa's Pygmy population, according to the London-based group Survival International. In Yaoundé, the nation's capital, Samuel Nnah, who directs Pygmy aid programs for a nongovernmental organization called the Centre for Environment and Development (CED), tells me he struggles against a federal government that allows timber companies to log Cameroon's rain forests, driving the Pygmies out. "The Pygmies have to beg land from the Bantu owners, who then claim they own the Baka," Nnah says.

On the road last February from Yaoundé to Djoum, a ramshackle town near Cameroon's southern border, I pass more than a hundred timber trucks, each bearing four or five huge tree trunks to the port of Douala. (Cameroon's 1,000-franc note, worth about $2, bears an engraving of a forklift carrying a huge tree trunk toward a truck.) At Djoum, the CED's provincial coordinator, Joseph Mougou, says he's battling for the human rights of 3,000 Baka who live in 64 villages. "Starting in 1994, the government has forced the Baka from their homes in the primary forest, designating it national parks, but the Baka are allowed to hunt in the secondary forest, mostly rat moles, bush pigs and duiker," Mougou says. "But that's where the government also allows the timber companies free rein to log, and that's destroying the forests."

Forty miles beyond Djoum along a dirt track, passing scores of fully loaded timber trucks, I reach Nkondu, a Pygmy village consisting of about 15 mud huts. Richard Awi, the chief, welcomes me and tells me that the villagers, each carrying empty cane backpacks, are about to leave to forage in the forest. He says that the older children attend a boarding school, but the infants go to the village preschool. "They'll join us later today," anthropologist Mesumbe says.

"Goni! Goni! Goni bule!" Awi shouts. "Let's go to the forest!"

In midafternoon, about 20 children between the ages of 3 and 5 stream unaccompanied into the clearing where their parents are fashioning beehive huts. "Pygmies know the forest from a young age," Mesumbe says, adding that these children followed jungle paths to the clearing.

It is nearing dusk when the three Bantu make their threatening entry into the clearing, demanding that we all return to the roadside village. When the villagers defy Joseph Bikono, the Bantu chief demands 100,000 francs ($200) from me as a bribe to remain with the Pygmies. First I ask him for a receipt, which he provides, and then, with one eye on his machete, I refuse to give him the money. I tell him that he's committed a crime and I threaten to return to Djoum and report him to the police chief, with the receipt as evidence. Bikono's face falls, and the three Bantu shuffle away.

The Pygmies greet their departure with singing and dancing, and they continue almost until midnight. "The Pygmies are the world's most enthusiastic partygoers," David Greer would tell me later. "I've seen them sing and dance for days on end, stopping only for food and sleep."

Over the next three days, I accompany Awi and his clan deeper into the forest to hunt, fish and gather edible plants. In terms of their welfare, the Baka here seem to fit somewhere between the Bayaka of a decade ago in the Central African Republic and the Batwa I had just visited in Uganda. They've abandoned net hunting and put out snares like the Bantu to trap small prey.

Sometimes, Awi says, a Bantu will give them a gun and order them to shoot an elephant. Mesumbe tells me that hunting elephants is illegal in Cameroon and that guns are very rare. "But highly placed policemen and politicians work through village chiefs, giving guns to the Pygmies to kill forest elephants," he says. "They get high prices for the tusks, which are smuggled out to Japan and China." The Pygmies, Awi says, get a portion of the meat and a little cash.

The Baka here have clearly begun accepting Bantu ways. But they cling to the tradition of revering Ejengi. On my final night with them, as light leaches from the sky, women in the clearing chant a welcome to the great rain forest spirit. The men dance wildly to the thud of drums.

As among the Bayaka, no sooner has the sky darkened than Ejengi emerges from the gloom, accompanied by four clansmen. The spirit's raffia strips are ghostly white. It dances with the men for about an hour, and then four little boys are brought before it. Ejengi dances solemnly among them, letting its raffia strips brush their bodies. "Ejengi's touch fills them with power to brave the forest's dangers," Awi says.

Unlike in Mossapola, where Ejengi lent the occasion the exuberance of a nonstop dance party, this ritual seems more somber. Nearing dawn, five teenagers step forward and stand shoulder to shoulder; Ejengi pushes against each of them in turn, trying to knock them off their feet. "Ejengi is testing their power in the forest," Awi tells me. "We Baka face hard times, and our youngsters need all that power to survive as Pygmies." The five young men stand firm.

Later in the day at Djoum, I meet the province administrator, a Bantu named Frédéric Makene Tchalle. "The Pygmies are impossible to understand," he says. "How can they leave their village and tramp into the forest, leaving all their possessions for anyone to steal? They're not like you and I. They're not like any other people."

Paul Raffaele is the author of Among the Cannibals.