Telluride Thinks Out of the Box

The fiction writer cherishes her mountain town’s anti-commercialism, as epitomized by the local swap stop, a regional landmark

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Telluride-Colorado-631.jpg)

One way to think about Telluride, Colorado, is as Aspen's younger, less glamorous, not so naughty sister. Telluride watched with envy and alarm as Aspen was transformed from low-key to outlandish, tomboy to sex symbol, its small businesses succumbing one by one to chic urban counterparts, haute-couture and -cuisine replacing Wranglers and hamburgers, hot tubs instead of horse tanks. Aspenization, I've heard it called. It conjures up a cautionary tale, the story of a town that made deals with developers, forsook its roots in ranching and mining and sold its soul for a hefty check.

Aspen residents saw too many of their open spaces filled with mansions and gated communities replete with movie stars. The locals found themselves dealing with traffic lights and traffic jams, then realized they'd priced themselves out of their own homes, property taxes having risen with the town's popularity. By the time everyone grew tired of the endless whine of private jets, Aspenization had become something to avoid—not so much Cinderella as Anna Nicole Smith. In Telluride, where I've spent all of my 48 summers, fear of following in the footsteps of a scary elder sibling has been around since the 1970s, when the first ski slopes began to open up.

Before that, Telluride had been in decline. In the '60s, the local mining company, Idarado, was extracting dwindling amounts of metals from the San Juan Mountains. The remaining miners were described, all too aptly, as a "skeleton crew": they rattled around the old ore-processing mill that stood between toxic ponds and hills of tailing. It could have been the setting of a creepy Scooby-Doo adventure; eventually it was a cleanup site.

My recollection of my family's early days in Telluride is one of dusty streets and oddball residents, an overabundance of roaming dogs, rusty implements hidden in brush and marsh (we had annual cause to evaluate each other's tetanus status), and abundantly available real estate. It was a town of things abandoned: people, pets, tools, jobs, homes. My family's summer houses (two miners' shacks, plus random sheds, with ten adjacent, gloriously empty lots for hanging laundry, throwing horseshoes, collecting rocks and planting aspen and spruce trees) were centrally located, up on a slight hill, in the center of the sunny side of town. There they stood along with Main Street businesses, banks and bankers, the old hospital (now the town's historical museum), Catholic, Baptist, Presbyterian and Episcopalian churches, grand Victorian homes of mining upper management and a remnant smattering of miners' cabins. The shady side, where the mountain's box canyon cuts off the winter sun, housed the ethnic miners and the prostitute cribs. The first condominiums went up there. From the sunny side of town you literally look down on the shady side; then, as now, the real estate rallying cry was "location, location, location."

My father and uncles (who were English professors in their other lives) became summer barkeeps, honorary deputies, temporary Elks Club members, Masons. They stocked fingerling trout; they were volunteer firemen. They hung around with people named Shorty and Homer and Liver Lips and Dagwood (who was married to Blondie). We decorated our Jeep and marched in the Fourth of July parades. In the 1960s, the transition from mining town to hippie enclave suited my family's temperament and budget. We'd been campers, and our miners' shacks were much-improved versions of tent or trailer. Graduate student drifters were our guests; some stayed on, becoming sheepherders or contractors or real estate agents.

The arrival of the skiers and condominiums sparked a plea for historic preservation and led to a strict set of building codes that remain in effect today. Gas stations are illegal within city limits as are neon signs and billboards. Modern structures have to fit into the town's historic scale and design. Just to change the color of your roof requires permission from the Historic and Architectural Review Committee (HARC). The codes are extensive.

Telluride is a beautiful place in which to wander, its gardens and houses well kept and properly scaled, the mountains themselves, protecting the little city in their bowl, forever breathtaking. Most of the stores are locally owned. There are no traffic lights, strip malls, box stores or massive parking lots. The ugliest thing within a 50-mile radius is the airport, and even it is set upon a stunning plateau, beneath majestic mounts Sunshine and Wilson and Lizard Head.

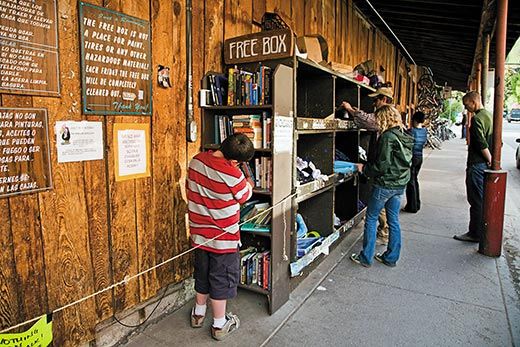

Along with HARC, another '70s arrival was the Free Box. It came from Berkeley, people said, and I suppose it was an early form of recycling: a bookcase-like structure into which people placed what they no longer needed and took what they liked.

The Free Box, situated a mere three blocks from my family's remaining house (still an uninsulated miner's shack resting on rocks rather than a real foundation, surrounded now by Victorian-style manors and manicured lawns), soon became the town's hub. There, locals would linger, glancing over its labeled shelves—boys, girls, men, women, books, housewares, jackets, shoes, etc.—to see what might be of use.

Over the years I've retrieved a down sleeping bag, coffee table, hammock, headboard, ice chest, file cabinet, sink, television and several typewriters (invariably with exhausted ribbons). My children have brought home countless toys and gadgets; guests have picked up temporary necessities, ski poles or sweatshirts, and returned them at visit's end. A hoard of young cousins brought home a giant papier-mâché cake with wooden handles and a trap door beneath its test-tube-size candles. Somebody had made it for a surprise party, built to allow a person (naked lady?) to pop out. The purple and white monstrosity sat in our yard for a few weeks, melting in the rain.

The Free Box is even a useful navigational tool. Place yourself there and west is out of town; east is toward the dead-end box canyon and inimitable Bridal Veil Falls; south is Bear Creek Road, the most popular hiking destination; and north leads—among other things—to our little house, crooked and dwarfed, on whose porch sit two perfectly good chairs carried home a few years ago from the Free Box.

In the old days, a man nicknamed the Polite Motorcyclist (he never revved his engine when he went by, coasting on gravity) stationed himself at the box, hand-rolling cigarettes and monitoring visitors. Brother Al, priest and civic servant, swept the sidewalk. For a while the city had essentially taken over the box's maintenance, which, the town manager estimated, amounted to something like $50,000 a year. Last fall some residents wanted to get rid of the box or at least have it relocated, complaining that the upkeep was costing the city too much and that it had become an eyesore—and it's true the contents were often of dubious use (broken crockery, half-filled food packages, outdated catalogs). To preserve the landmark, a local citizen's group, Friends of the Free Box, stepped in and since the winter have taken over the care of the box, posting a bulletin board to list big items and hauling away trash.

Still, in a town that every year seems to grow closer and closer to that place it feared becoming—movie stars and other extraordinarily wealthy people live here now; the gated communities and private jets have arrived; articles on the need for "affordable housing" run alongside the ubiquitous Sotheby Realty ads in the town newspaper—I don't think I'm alone in clinging to the markers of Telluride's resistance. The Free Box is one of those, a small patch of common ground. Drop off a DVD of a Cary Grant movie and see it fly into a stranger's parka pocket; hold up a black cashmere sweater and get a nod of approval—lucky you, to grab it first—from the thrift-store maven. Send the kids out to occupy themselves, to discover some curiosity or treasure there. Later, you can give it back.

You take and you give, give and take. Maybe we can reassure ourselves we won't entirely turn into Aspen if we still have the Free Box.

Antonya Nelson's Nothing Right is the latest collection of her short stories.