Shadow Wolves

An all-Indian Customs unit possibly the world’s best trackers uses techniques to pursue smugglers along a remote stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border

On a brickoven hot morning somewhere southwest of Tucson, Arizona, U.S. Customs patrol officer Bryan Nez holds up a hand in caution. Dead ahead lies a heavy thicket, an ideal spot for an ambush by drug smugglers. Something has rousted a coyote, which lopes away. Nez keeps his M16 trained on the bushes.

“Down, now,” he whispers. We crouch on the hot, sandy desert floor. My heart is pounding, and I fully expect smugglers to step out of the bushes with guns drawn. Instead, Nez whispers, “Hear it?” I can’t at first, but then I detect a faint buzzing. In seconds, a dark cloud of insects swarms by not a dozen feet from us. “Probably killer bees,” says Nez, getting up and moseying on. False alarm.

Nasty insects seem the least of our problems. The temperature will soon top 107 degrees. We’ve been out on foot for an hour tracking drug smugglers, and large moon-shaped sweat stains form under the arms of Nez’s camouflage fatigues. He carries a Glock 9-millimeter pistol in a vest along with a radio, a GPS receiver and extra ammunition clips. On his back is a camel pack, or canteen, containing water; Nez will wrestle with heat cramps all day.

But the 50-year-old patrol officer doesn’t have time to think about that. We’re following the fresh tracks of a group of suspected smugglers he believes have brought bales of marijuana from Mexico into Arizona’s Tohono O’odham Nation reservation.

A full-blooded Navajo, Nez belongs to an all-Indian Customs unit, nicknamed the Shadow Wolves, that patrols the reservation.The unit, which numbers 21 agents, was established in 1972 by an act of Congress. (It has recently become part of the Department of Homeland Security.) “The name Shadow Wolves refers to the way we hunt, like a wolf pack,” says Nez, a 14-year veteran who joined the U.S. Customs Patrol Office of Investigation in 1988 after a stint as an officer with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Navajo Police Department. “If one wolf finds prey, it will call in the rest of the pack.” What makes the Shadow Wolves unique is its modus operandi. Rather than relying solely on high-tech gadgetry— night-vision goggles or motion sensors buried in the ground—members of this unit “cut for sign.” “Sign” is physical evidence—footprints, a dangling thread, a broken twig, a discarded piece of clothing, or tire tracks. “Cutting” is searching for sign or analyzing it once it’s found.

Nez relies on skills he learned growing up on the Navajo Nation reservation in northern Arizona, and he cuts sign like other people read paperbacks. Between October 2001 and October 2002, the Shadow Wolves seized 108,000 pounds of illegal drugs, nearly half of all the drugs intercepted by Customs in Arizona. The group has also been invited to Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Kazakstan and Uzbekistan to help train border guards, customs officials and police in tracking would-be smugglers of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons.

At home, the Shadow Wolves unit is responsible for the 76 miles of border that the reservation shares with Mexico. It’s a difficult task for fewer than two dozen officers, and the events of September 11 have only made things worse. Beefed-up security at Arizona’s designated border crossings— Nogales and Sasabee in the east, tiny Lukeville in the west—has pushed smugglers, both on foot and in trucks, toward the remote and less guarded desert in between. Now, day and night, groups of eight to ten men move north from Mexico toward the insatiable U.S. market, each individual carrying upwards of 40 pounds of marijuana on his back. Funded by Mexican drug lords, the smugglers are often better equipped, better funded and more numerous than the Shadow Wolves, with lookouts on neighboring mountains armed with night-vision goggles, cell phones and radios capable of delivering encrypted messages to direct smugglers away from law enforcement vehicles.

Violence between pursuers and pursued has been minimal. Until recently. In April 2002, a group of officers was making an arrest near Ajo when a smuggler tried to run down Shadow Wolves agent Curtis Heim with his truck. Heim, only slightly injured, shot the smuggler, who survived the wound but was arrested, his drugs confiscated. (That bust brought in a whopping 8,500 pounds of marijuana, which could have sold on the streets for an estimated $8.5 million.) This pastAugust, Kris Eggle, a 28-year-old park ranger at the OrganPipeCactusNational Monument, just to the west of the reservation, was shot and killed by a Mexican fugitive he was pursuing.

Today’s hunt got under way at 6 a.m., two hours after Nez’s shift began, following a radio call from fellow Shadow Wolf Dave Scout, 29, an Oglala Sioux who had discovered fresh tracks eight to ten miles from the unit’s headquarters in the Indian village of Sells while patrolling in his truck.

But now, at midmorning, and an hour after our encounter with the bees, we are still following the trail. The desert stretches endlessly in every direction. Paloverde trees, mesquite and dozens of cactus species, especially saguaro, barrel and prickly pear, dot the steep mountains and hills, plains and valleys. At 2.8 million acres, southern Arizona’s Tohono O’odham Nation reservation (pop. 11,000) is fourfifths the size of Connecticut. There are no cities on it, only small and widely scattered villages.

Nez stops and points to a patch of desert near my foot. “See that square shape and those fine lines you’re almost standing on?” he asks, directing my attention to some nearly indeterminate scratches in the sand. I hastily step back. “That’s where one of them took a break. That mark is where he rested a bale of dope. I’m guessing we’re a couple of hours behind them, because you can see that spot is in the sun now. This guy would have been sitting in the shade.”

The tracks continue north into an open area, cross a powdery road, then head off toward another thicket. Nez observes that the smugglers probably crossed here during the night; otherwise they would have avoided the road or at least used a branch to cover their tracks.

Fortunately, they didn’t. “There’s our friend Bear Claw,” Nez says, referring to a man they’ve been tracking whose footprint looks like a bear’s. “And over there? See the carpet shine?” To hide their tracks, smugglers will tie strips of carpet around their feet, which leaves a slight sheen on the desert floor. I can just barely see what he’s talking about.

These footprints are fresh, says Nez. “We look for fine, sharp edges on the imprint made by the bottom of the shoe, and whether the wall is starting to crumble.” Tracks of animals, bugs or birds on top indicate a print has been there awhile. But “if the animal or insect track is obscured by a footprint as it is here, then the tracks are recent.” Also, says Nez, after a few hours “there would be twigs or bits of leaves in them.”

He moves to another set of tracks. “This one is a female UDA,” he says, using the acronym for undocumented alien, a person who entered the country illegally. Nez has deduced the hiker’s sex and status from the lightness of the print (the person is not carrying a bale) and its shape. “The footprint is more narrow, and there are more steps because she has a shorter step than the men,” he explains.

UDA tracks are more numerous than smugglers’. In the first place, there are a lot more of them. Then, too, if they get separated from their guides or are abandoned by them, UDAs can wander in circles for miles, lost and looking for water. In summer, when temperatures can hit 118 degrees, many die. Between January and October 2002, seventy-six UDAs died from the heat in southern Arizona alone. Shadow Wolves officers carry extra water and food for their almost daily encounters with them. (When they do meet up with UDAs, they call the Border Patrol or just let them go.)

We push through some scrub, and Nez points to a broken bush I hadn’t noticed. “Someone stepped on it. Look at the direction it’s bent.” He steps on the bush, and sure enough, it points like an arrow in the same direction as the tracks.

A few minutes later, Nez draws my attention to a branch of a mesquite tree. Squinting, I finally make out a single, dangling thread. “That’s a fiber from the sugar sack they use to carry the dope in,” he says. “And here,” he points a foot farther, “see where this branch has snapped? One of these guys plowed through here. Look at the break. See how the wood inside is fresh and moist?” As a broken twig ages, the wood darkens and the sap thickens. The smugglers cannot be far ahead.

Now Nez pays even closer attention to the tracks. He is looking for “shuffle” marks, which would show that the quarry knows they are being pursued. “Shuffle marks indicate that they’ve stopped to turn around and look behind them,” says Nez. “That’s when you move off the tracks and come up the side of them.”

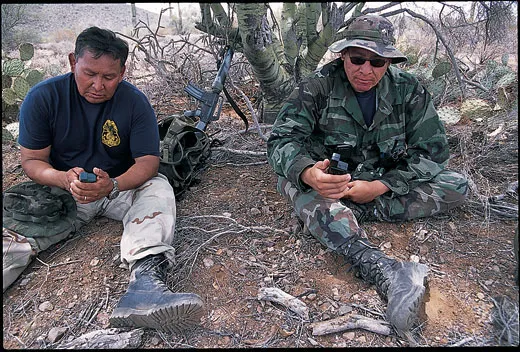

Thirty minutes later, we find ourselves at the base of a steep incline. At this point, Scout drives up in his pickup truck. In contrast to Nez’s easygoing manner, Scout looks serious and taciturn. He says he thinks the smugglers have holed up somewhere up the hill, waiting for dark before they move. Scout radios Al Estrada, his supervisor in Sells, who says he’ll send two more Shadow Wolves—Sloan Satepauhoodle, a Kiowa from Oklahoma (and one of only two women in the unit), and Jason Garcia, an O’odham who grew up here.

An hour later, Satepauhoodle and Garcia show up in a pickup, unload a pair of all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and head up the hill. Scout and Nez drive to the other side of the hill and resume tracking.

Over the next two hours, neither Scout, Nez nor the officers in the ATVs pick up even a hint of the smugglers’ trail. It is now past 1 p.m., an hour after the end of the agents’ shift. Satepauhoodle and Garcia pack up their ATVs and drive home. But Nez is fidgety. “I just have a feeling they’re up there,” he says to no one in particular. Scout and Nez agree to go back to the ridge where the trail was lost and try again.

The slope of the ridge consists mostly of loose rock and small pebbles, and Nez and Scout notice some faintly discolored stones. These were probably turned over by a passing foot, revealing a damp, slightly darker side.

Thirty minutes later, Nez holds up a hand. We freeze. He and Scout creep forward, firearms at the ready.

“We found the dope,” Nez calls out, wiping his face with his handkerchief and summoning me to join him next to a large mesquite tree. I don’t see any drugs. Nez tells me to look more closely. Under the tree, obscured by broken branches and hidden by shadow, I make out a number of bales. The agents on the ATVs had driven right by this spot. “Smell it?” Nez asks, smiling. Oh, yeah.

A few yards away, more bales are stacked under another tree. I help Nez and Scout pull them into a clearing. There are nine in all, each wrapped in plastic sheets and duct tape, and stuffed inside a burlap sugar sack to form a three- by four-foot package. To carry the drugs, the smugglers had rolled empty sacks into rudimentary shoulder straps and fastened them to the bales to make crude backpacks. Scout calls in GPS coordinates to the office in Sells.

We sit on the bales and wait for reinforcements to come take them, and us, back to Sells. I ask Nez if he gets frustrated by the job. He answers no. “I like the challenge. But mainly I think about the young kids,” he says. “It’s satisfying to know that we are keeping at least some of the drugs from getting onto the streets and into the hands of children.”

As we are talking, Scout leaps up and sprints into some nearby bushes, his gun drawn. Nez jumps up and races after him. I see a quick flash of a white T-shirt and watch as Scout and Nez disappear into the mesquite and greasewood.

Minutes later, the pair returns. Two smugglers had stayed behind with the drugs. Nez and Scout had to let them go— the chances of a violent encounter were too high in the thick foliage, and Shadow Wolves officers are under orders to remain with any drugs their unit turns up.

Twenty minutes later, Nez points to a spot about 1,000 feet straight up, at the top of the ridge. The two smugglers are looking down at us. They scramble over the top and disappear.

“Those guys are starting to annoy me,” says Nez.

“Yeah,” Scout agrees. “I want them.” He makes a call on his radio and reads out some coordinates. In 15 minutes, we hear the pulsing thwacks of a Blackhawk helicopter, which has flown out from Tucson and now heads over to the other side of the hill.

After several minutes, the helicopter disappears behind the ridge. We learn by radio that the two men have been caught and taken to headquarters in Sells.

“These guys were pretty beat,” says David Gasho, an officer on board. “They didn’t even try to hide.” The helicopter had landed on a flat patch of desert. The Customs officers inside the helicopter, Gasho relates, had simply waited for the two men to reach them. They had offered no resistance.

The men claim not to be smugglers, mere UDAs who got scared and ran when they saw the officers. But interrogated separately back in Sells an hour later, they quickly confess. The men, ages 24 and 22, say they’d been hired right off the street in Caborca, Mexico, some 60 miles south of the border, and had jumped at the chance to make $800 in cash for a few days’ work—a bonanza considering that top pay at the local asparagus plant is $20 a week.

Because the men confessed, says an O’odham police department sergeant, they’ll be prosecuted at the federal court in Tucson. As first-time offenders, they’ll probably get ten months to one and a half years in a federal prison. Then they’ll be sent back to Mexico. Chances are high that the seven smugglers who got away, including Bear Claw, will be back humping bales of marijuana in a matter of days.

Nez and Scout look beat, but they are smiling. It has been a good day, better than most. The officers can go for weeks at a time without making an arrest. Rene Andreu, the former resident agent in charge at the Sells office, speculates that Shadow Wolves capture no more than 10 percent of the drugs coming into the reservation. “In recent years, we’ve averaged about 60,000 pounds a year,” says Andreu. They all agree that they need greater resources.

It will take more than a few reinforcements, however, to have any real effect on drug traffic. The Shadow Wolves know this dismal fact all too well. Still, without their dedication and that of other Customs officials, smugglers would be bringing drugs over the border, as one officer put it, “in caravans.”