Environmental activist and author Edward Abbey spent two seasons, in 1956 and 1957, working as a ranger in what's now Arches National Park in Utah. In Desert Solitaire, his account of those two summers, Abbey writes, "Standing there, gaping at this monstrous and inhumane spectacle of rock and cloud and space, I feel a ridiculous greed and possessiveness come over me. I want to know it all, possess it all, embrace the entire scene intimately, deeply, totally...."

While most can't compete with Abbey's eloquence, I'd venture to guess that the majority of the 1.5 million annual visitors to the red-rock paradise have something to say about the park's magnificence and beauty.

And it's not necessarily something so nice. Well, at least for one person, who left this scathing review: “Looks nothing like the license plate.” Of course, referring to the standard issue plate featuring Delicate Arch, a 46-foot-tall freestanding sandstone arch, and the state slogan, "Life elevated."

It's bitter reviews like this one that illustrator Amber Share savors. She runs the Instagram account Subpar Parks, which pairs illustrations of national parks with the ridiculously unsavory reviews they’ve received online. The account, launched in 2019, currently has more than 100 posts of artistically drawn national park posters superimposed with real negative reviews she's gathered from Yelp, Google and TripAdvisor. The popular Instagram account has spawned a new book, Subpar Parks: America's Most Extraordinary National Parks and Their Least Impressed Visitors, out this month.

Subpar Parks: America's Most Extraordinary National Parks and Their Least Impressed Visitors

Based on the wildly popular Instagram account, Subpar Parks features both the greatest hits and brand-new content, all celebrating the incredible beauty and variety of America’s national parks juxtaposed with the clueless and hilarious one-star reviews posted by visitors.

“At the time [I created the account], I was working more in graphic design and I wanted a side project to keep me illustrating and hopefully break into the outdoor industry a bit,” Share says. “A natural idea that emerged was drawing all the parks. Obviously, that’s been done a lot and executed really well by a lot of really awesome artists. So I thought, ‘What could I do to put my spin on it and make it my own, stand out a little bit?’ One day I just happened to stumble upon a couple of bad reviews someone posted to Reddit, and immediately thought I could find this for every park.”

The first park she illustrated for the Instagram account was Arches and its non-license-plate-worthy scenery. Once she put up a few more and shared the account, the project took off. With more than 350,000 followers, the account has been called "an immediate hit," taking "creativity to a whole new level" and providing "comic relief in strange times." Soon enough, literary agents were sliding into Share's DMs to get her to create a book with them.

Out of all the National Park Service’s 423 national park sites, only 63 of them have the “National Park” designation tacked onto their name. From Acadia to the Grand Canyon, and Denali to the Virgin Islands, all 63 are featured in the book. Share also includes a handful of national monuments, recreation areas, preserves, lakeshores and seashores, bumping the full list of sites in its pages up to 77. A nature lover who enjoys hiking, kayaking and backpacking, Share has been to about a third of the sites.

The Raleigh, North Carolina-based designer had some strict criteria when it came to determining which reviews to use in her illustrations. She looked for reviews that predated the project; once it took off, people began to plant fake reviews to get her attention. Then, she tried to weed out any sarcastic ones, and others that criticized park management or administration.

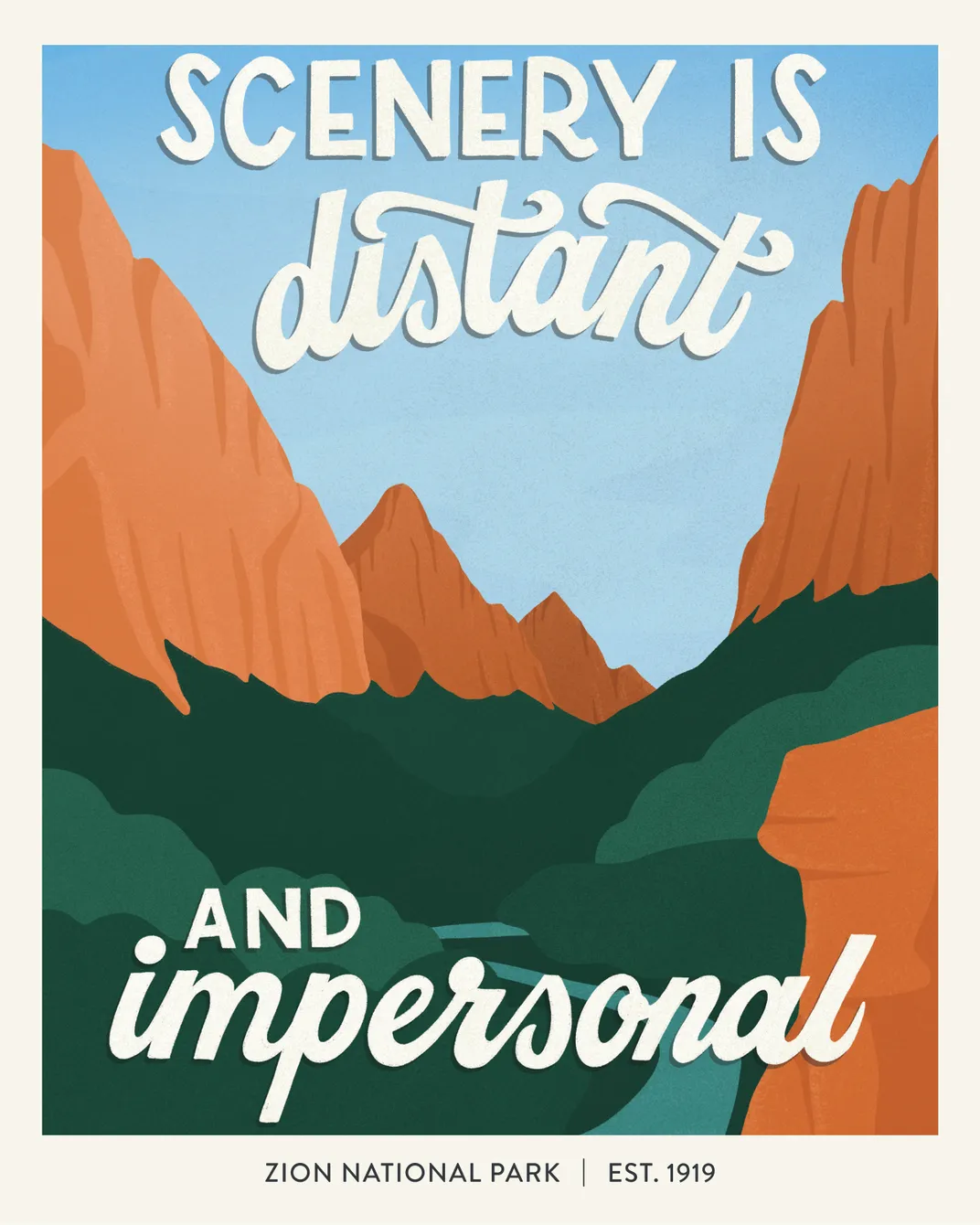

“I really try to focus in on people just criticizing nature because that, to me, is what keeps it funny and light,” she says. “You could go on all day about the ways that Zion manages the shuttle system, and that’s not really what this is about. But somebody who thinks the scenery of Zion is distant and impersonal is really what gets me.”

As for the glass-half-empty people that wrote the reviews, Share hasn’t heard from any, and doesn’t try to contact them either. “I just don’t really see that as a productive avenue,” she says. “I imagine most people probably don’t even remember that they wrote the review that I pulled. If you think about the mindset you’re in when you just quickly pen a little review, you probably don’t really remember it after a while.”

No matter what the critics say, these six national parks, all in the book, are particularly impressive.

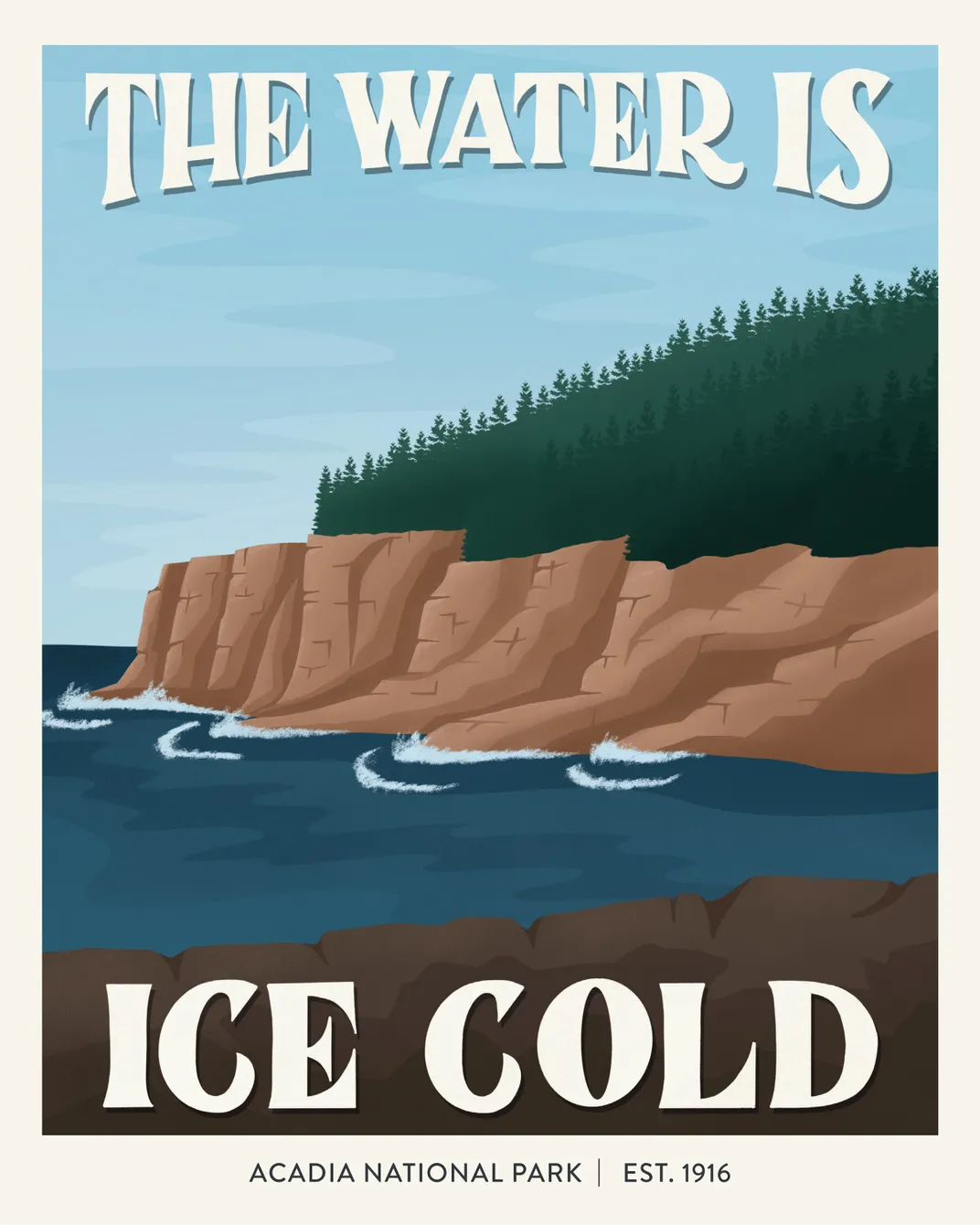

Acadia National Park, Maine

Maine’s 47,000-acre Acadia National Park, the first national park east of the Mississippi, opened to the public in 1919. Contained within the coastline cliffs and beaches is the 1,529-foot-tall Cadillac Mountain. There's also wildlife like black bears, moose and, just off the coast, finback, humpback and minke whales. Mount Desert Island, making up most of the park, is crisscrossed with hiking trails and scenic roadways.

“I’ve never seen a beach like the beaches on Acadia,” Share says. “The rugged, sort of rocky, pine tree evergreen coastline blew my mind. I went and saw the sunrise on Cadillac Mountain, and it was a spiritual experience.”

That being said, the review—"The water is ice cold"—isn’t wrong. The waters off of Acadia have a chilly reputation, only getting up to about 60 degrees in the summertime. Share experienced this herself. “The water was pretty cold, I will say," she says. "I dipped my feet in and was like, ‘This isn’t that bad, but I would not put my whole body in it.’" Someone responded [to her comment] with, "That should just be the slogan for all of Maine’s beaches," she adds.

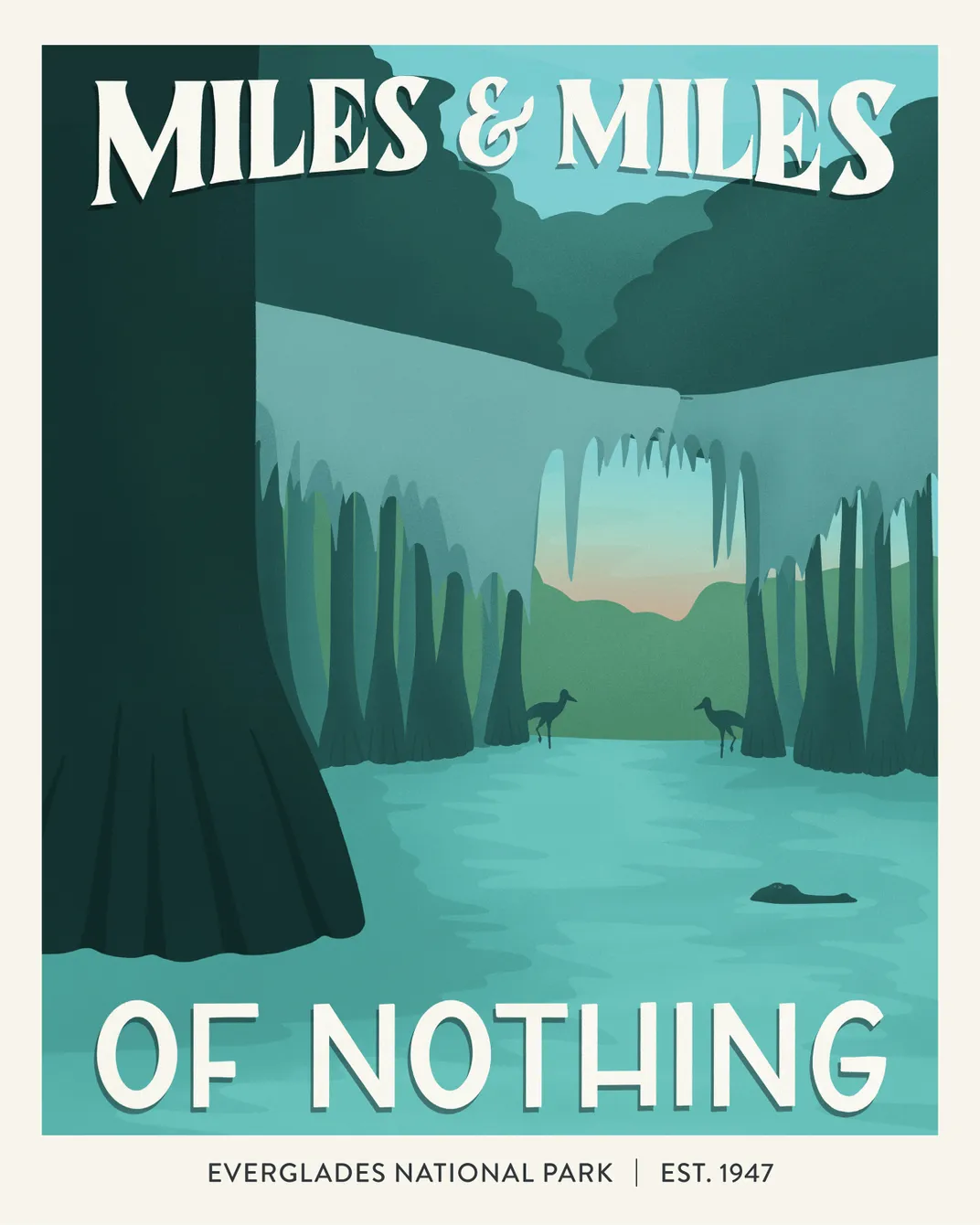

Everglades National Park, Florida

Everglades National Park in Florida stretches 1.5 million acres, protecting nine different wilderness habitats including mangrove, freshwater slough and estuary. It’s a unique park overall; when it was created in 1934, it was the first wilderness area to be protected for the diversity of its flora and fauna.

“I can kind of see how if you’re just looking superficially at the marshy grasses going on forever, it’s like, ‘Oh, it’s nothing,’” Share says. “But there’s just so much in there that to call it ‘miles and miles of nothing’ is just so, so comical to me.”

Beneath the surface of those miles of "nothing," as one reviewer so blithely put it, are endemic species (like the saw palmetto plant and the snail kite bird), crocodiles, manatees, fish, and more. Above the "nothing," you’ll see panthers, some 360 species of birds and more than 100 miles of waterway to explore by boat. But you have to look beyond the initial view.

“The ranger spoke so beautifully,” says Share, recalling an interview she did for the book. “She was saying how a lot of parks out west are parks that scream at you, and you get why they are national parks immediately. But she told me that Everglades is a park that whispers. Doesn’t that just give you the chills? It’s one of those that you really have to sit with and take the time to let it seep in.”

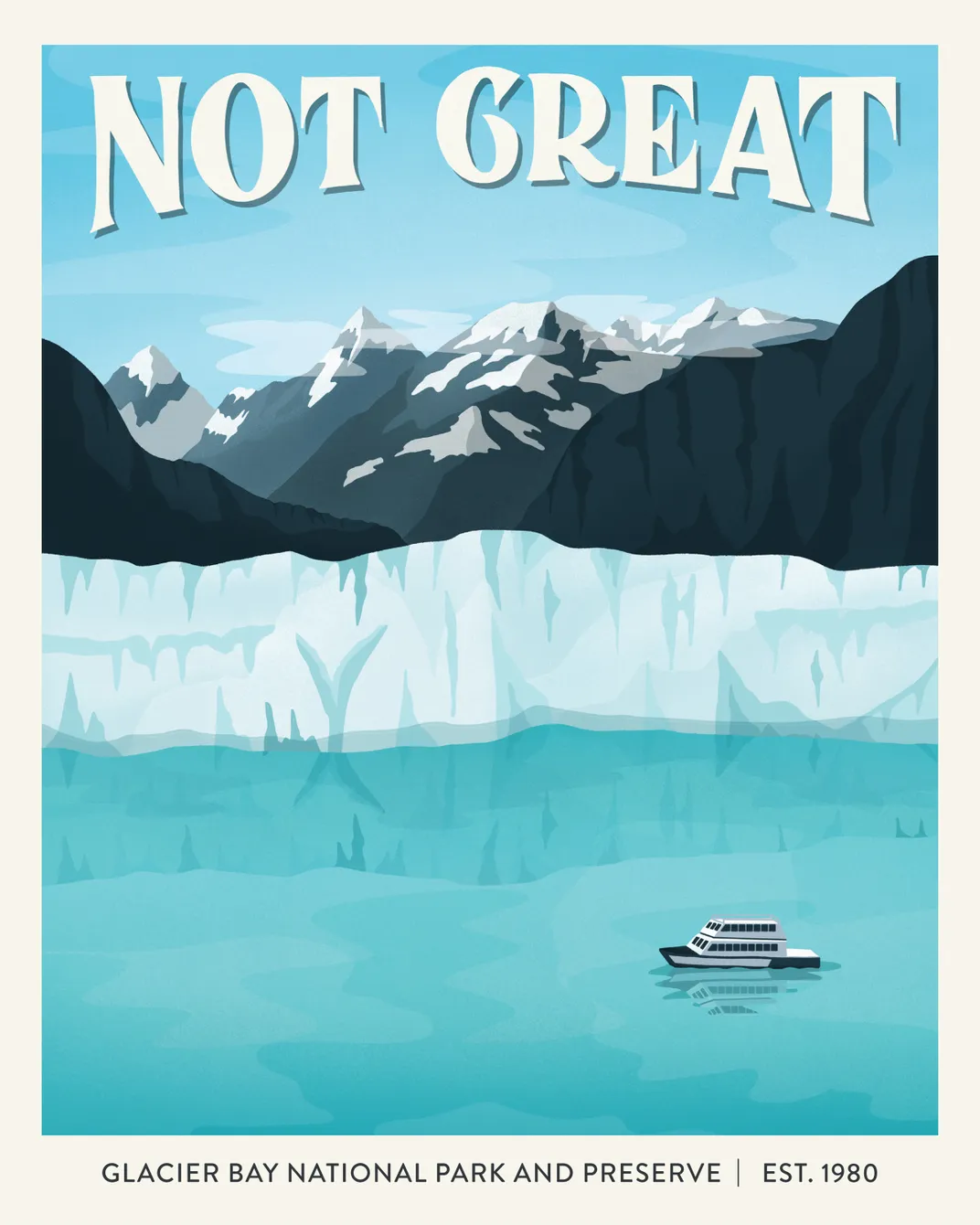

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska

The indigenous Tlingit people in Alaska have a term for the noise that comes from Glacier Bay: white thunder. It refers to the sound of glaciers calving off into the water. Located in southeast Alaska just below the Tongass National Forest and west of Juneau, Glacier Bay has the world’s largest concentration of tidewater glaciers that are actively calving. And when it happens, you can both hear it and see it—often from the deck of what feels like a toy boat pluncked down in enormous scenery.

The review Share found—"Not great"—was especially curt. “It’s such a stunning and mind-blowing place,” she says.

The park, which is only accessible by plane or boat followed by a quick drive into Bartlett Cove, opened in 1925 and was expanded in 1978. Today, it encompasses 3.3 million acres chock full of fjords, rainforest, coastline, mountains and those colossal glaciers. You can also catch a glimpse of humpback whales, puffins, sea lions and sea otters. Share says the best way to explore the park for a beginner is on one of the eight-hour boat tours offered by the Glacier Bay Lodge.

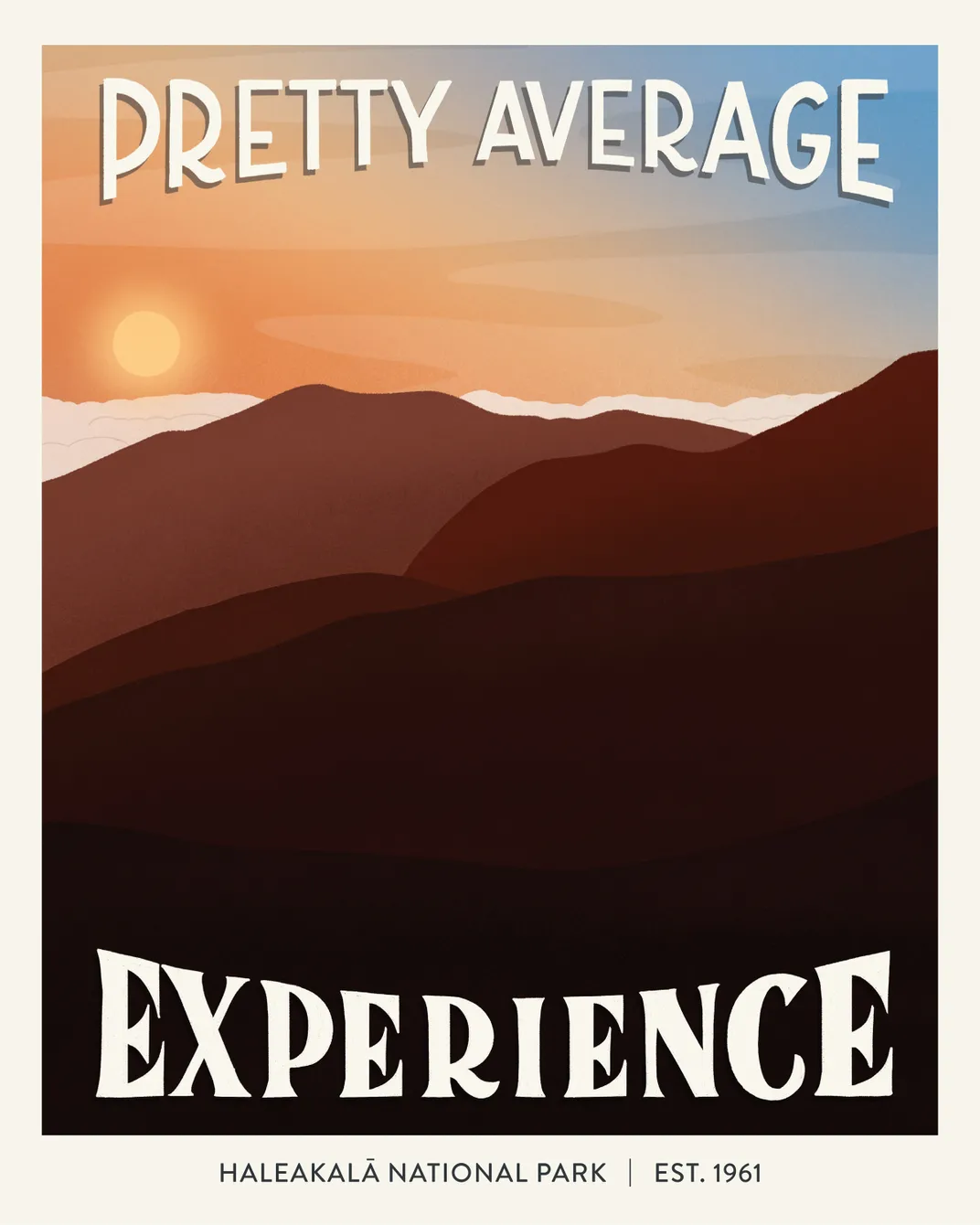

Haleakala National Park, Hawaii

When Share was 10 years old, she lived in Hawaii while her dad served in the Navy. During that year, her family enjoyed the stunning overlooks along Maui's 52-mile Road to Hana, also known as the Hana Highway, that leads to Haleakala National Park.

Established in 1976, the 33,265-acre park is split into two sections: the Summit District and the Kipahulu District. The Summit District is home to the park’s namesake volcano—with an elevation of more than 10,000 feet. “I remember freezing,” Share says. “I was so cold up on [Haleakala]. You don’t really think of Hawaii as a place with super high elevation.” The Kipahulu District encompasses the rest of the park and all its wild green landscapes, endemic species (native bats, seals and sea turtles), ocean views and waterfalls.

Haleakala is the world's largest dormant volcano, and its summit is considered the quietest place on Earth. Plus, Haleakala has the largest concentration of endangered species of all the national parks. So the review Share found—"Pretty average experience"—really stuck out.

“What people also don’t realize is how Haleakala is not just the top of a volcano,” says Share. “There’s the entire other district. So it’s really funny to me to call it a ‘pretty average experience’ when there are a lot of different things you could do there, and it’s also one-of-a-kind landscapes that you can’t get anywhere else.”

Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

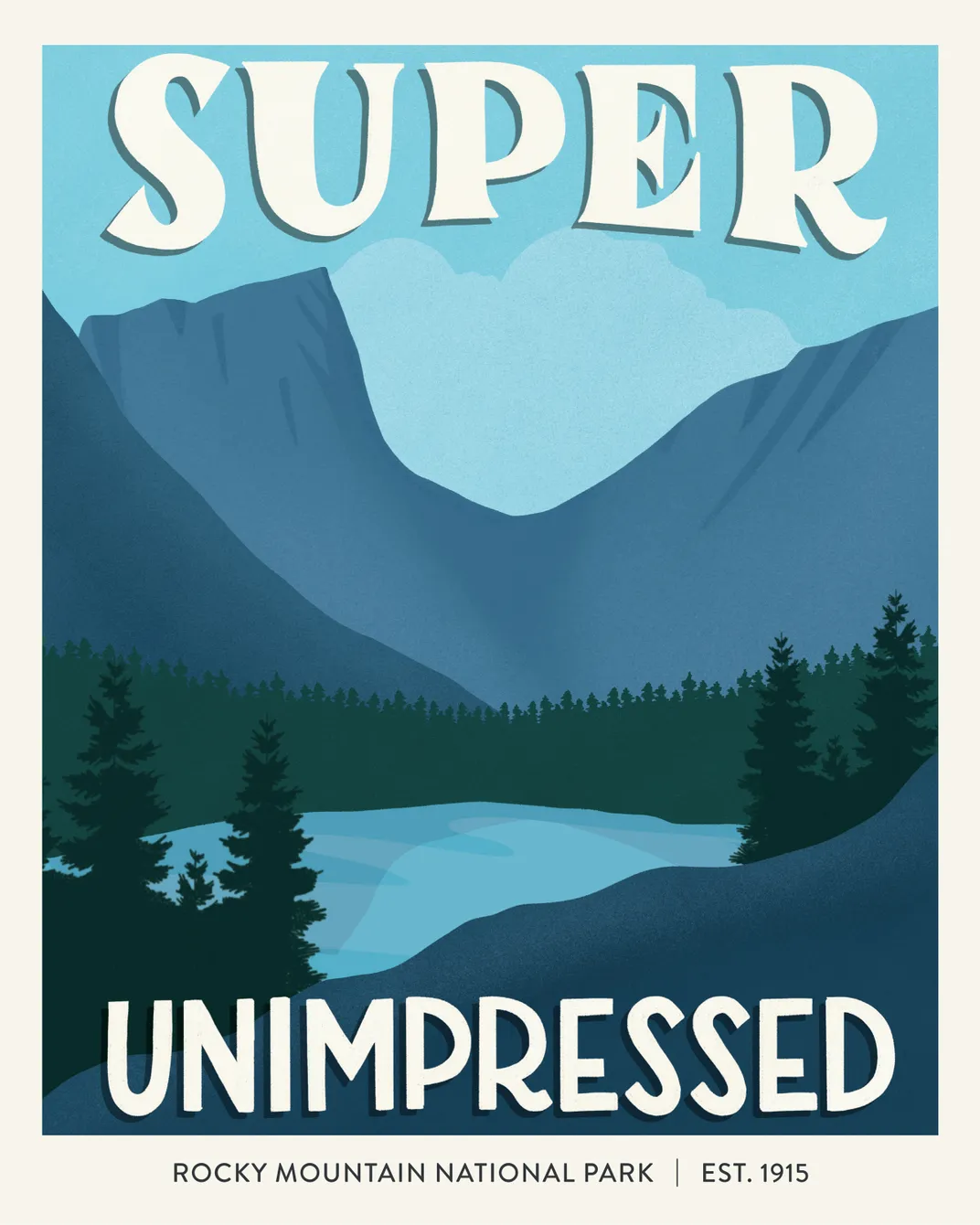

Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado is truly a magnificent place. At 7,800 feet to 12,183 feet in elevation, it’s one of the highest national parks in the country, and it boasts the highest continuously paved U.S. highway, Trail Ridge Road. The 415-square-mile park contains 77 mountain peaks, hundreds of wildlife species and more than 300 miles of trails. Plus, a third of the park is stunning alpine tundra, sitting above the line where trees can grow in Colorado, between 11,000 and 12,000 feet elevation.

“We drove from west to east, and we stopped to do a hike,” recalls Share, of a trip she took in June this year. “Even if you just do the drive, you wind up going from the very bottom elevations of the park up to the alpine area, so you’re just hitting all the different elevations that are available in the park to explore. You’re in wildflowers in one part of the park and there’s still, in other parts, snow drifts that are taller than me. It’s just such a varied experience.”

That's why she was shocked—and amused—by a review that said simply, "Super unimpressed."

Rocky Mountain National Park, which was established in 1915, is still recovering from the 2020 wildfire season, so check to see if your preferred hiking routes and activities are currently available. And remember, if you’re from a low elevation, be sure to drink a lot of water and listen to your body—the adjustment is more difficult than you think.

Zion National Park, Utah

At only 229 square miles, Zion National Park in Utah is pretty small compared to some of the other national parks, but it is one of the most crowded. Drivable from a number of urban areas, and all over Instagram, it pulls first-time national park visitors out to see the sights. Those sights include the 15-mile-long, 3,000-feet-deep Zion Canyon; the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway with its switchback roads and scenic sweeping views that catch waterfalls in the right season; and 1,500-year-old Anasazi cliff dwellings and petroglyphs. Human history in the park dates back more than 10,000 years, though it was only established as a national park in 1919.

Share found this winning review of Zion: "Scenery is distant and impersonal."

“This is the park most people have on their bucket list cause they’ve seen Angels Landing on Instagram,” Share says. “It’s not this huge expansive park the way that Yellowstone or Yosemite are, so [the review is] even funnier to me because I’m like, ‘The scenery of Zion is not actually that distant cause Zion’s not even that big.’ You can do a hike like Observation Point or Angels Landing, where you have these wide open vistas of all of these incredible cliffs, but then you can also do something like The Narrows, where the rocks are literally up in your face while you navigate the narrow canyon.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/72/fc725bf7-682a-4413-9cdd-c339928df165/haleakala_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/11/1a1107f6-c9bb-4913-bd9b-4545d80477da/haleakala_header.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)