A Brief History of America’s Most Outrageous Dentist

Painless Parker and his dental circus live on in a Philadelphia museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/1a/2f1a3b8d-dfb8-4f25-8e6b-a75f9e6751e6/196622.jpg)

Having a tooth pulled in the early 1900s was anything but awful. You’d climb up into the back of a traveling caravan, surrounded by a booming brass band, sparkling costumed women, and next to a bucket of pulled teeth carried by a dapper gentleman with a goatee. In time with the band's cheerful tune, out would come your tooth, guaranteed to be a painless—and even entertaining!—extraction.

Well, not quite. Victims of this ruse, run by the famed dentist Painless Parker and his Dental Circus, often left the appointment hoarse from their screams of pain. And at the Kornberg School of Dentistry's Historical Dental Museum Collection at Temple University in Philadelphia, you can pay homage to the dentist's colorful, if misleading, claims by visiting a selection of his grisly artifacts—from a bucket of teeth to the strung-tooth necklace and advertisements he used to lure in customers.

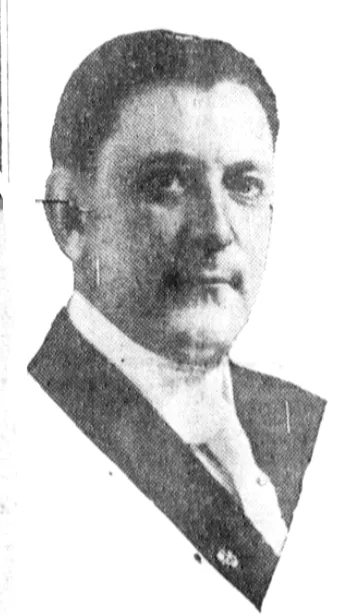

Edgar Randolph “Painless” Parker began his dental practice in 1892, after his graduation from the Philadelphia Dental College (now the Temple University Maurice H. Kornberg School of Dentistry), when dentistry for widespread tooth decay was still emerging as a profession. According to the college’s current dean, Dr. Amid Ismail, Parker was a terrible student and only graduated because he pleaded with his dean to pass him. The dean did, and Parker moved home to Canada to start work as a dentist.

But there was a problem. At the time, it was considered unethical in the profession to solicit patients, so Parker found that after six weeks, he still hadn’t seen a single client. He decided to toss ethics to the wayside and start an advertising campaign. In exchange for a new set of dentures, Ismail told Smithsonian.com, the desperate dentist bartered with a sign maker for a placard that read “Painless Parker.” His business idea was deceptively simple: He would inject patients with a solution of watered-down cocaine and pull their teeth. The 50-cent extraction would be painless, he said, or he'd pay the patient $5.

When Parker first became a dentist, most offices (called dental parlors at the time) were incredibly unsanitary and the dentists there were usually unlicensed. People didn’t want to go, so they tended to treat themselves at home with narcotic-laced over-the-counter medication. Parker began his practice to take advantage of the current dental atmosphere—lack of trained practitioners and patients’ fears of pain. He concocted the cocaine solution, but it didn’t always work—sometimes he just gave his patients a glass of whiskey instead.

But Parker wasn't content to stop there. Donning a top hat, coattails and a necklace he made out of teeth (supposedly the 357 teeth he pulled in one day), he partnered with William Beebe, a former employee of P.T. Barnum, to create a traveling dental circus in 1913. At the show, Parker would bring a pre-planted person out of the audience and pretend to pull out a molar, showing the audience an already-pulled tooth he was hiding as evidence that the extraction was completely painless. Then, accompanied by a brass band, contortionists and dancing women, real patients would climb into the chair for the same procedure.

While he pulled the tooth out, still for 50 cents an extraction, Parker would tap his foot on the ground to signal the band to play louder—effectively drowning out the patient’s pained screams. He still used the cocaine solution—but instead of injecting it to numb the mouth, he'd squirt it into the cavity—and that only worked sometimes, if at all. Still, Parker managed to become popular. Dental patients and visitors liked the distraction of the brass band and the rest of the circus. Thanks to the band, no one heard the moans—and everyone but the hapless patient assumed the treatment didn’t hurt a bit.

But when Parker moved to California, he left a horde of angry, hurting patients in his wake. The man who duped his aching patients was detested by his colleagues, too—the American Dental Association even called him “a menace to the dignity of the profession.”

“Any positive patient stories are likely to be fake,” Ismail said. “Painless Parker was sued many times and lost his dental licenses in several states. He was a showman more than a real dentist, and he cared more about providing expensive dental care than care that would actually benefit the health of his patients.”

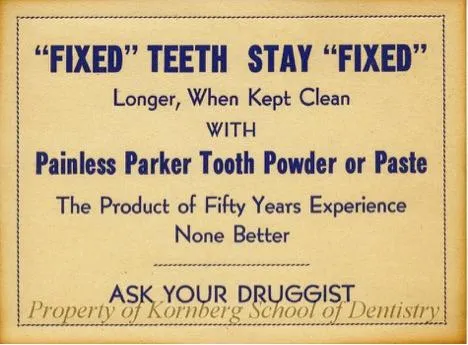

He legally changed his name to Painless Parker in 1915, Ismail said, opening up a chain of about 30 Painless Parker Dental Clinics on the west coast. The clinics hawked dental services and a line of dental care products—the first of their kind. Though Parker was a huckster and, arguably, a con man, his contribution to the dental world is undeniable. Not only was he the first to openly advertise and open a chain of clinics, but in a backwards way, he can also be considered a founding father of good dental practices.

“Parker’s most indisputable legacy to the field of dentistry is his contribution, through his bad acts, charlatanism and relentless pursuit of profits, to the development of professional ethics in dentistry,” Ismail said.

Today, those ethical principles would make activities like Parker’s unthinkable—though, ironically, his bloody actions helped inspire them. And even if the idea of being treated in a circus-like setting is, in modern times, the ultimate dental nightmare, artifacts from his practice make for good viewing. Parker’s tools at the museum stand alongside a large collection of objects that bring the history of American dentistry to life—everything from vintage dentures to early toothbrushes and dental instruments.

Parker and this collection "also serves as a warning to consumers even today,” mused Ismail. “Scientific evidence must remain the foundation of clinical care in any health field. Otherwise we will be victims to modern charlatans.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)