Point. Shoot. See

In Zambia, an NYC photographer teaches kids orphaned by AIDS how to take pictures. They teach him about living

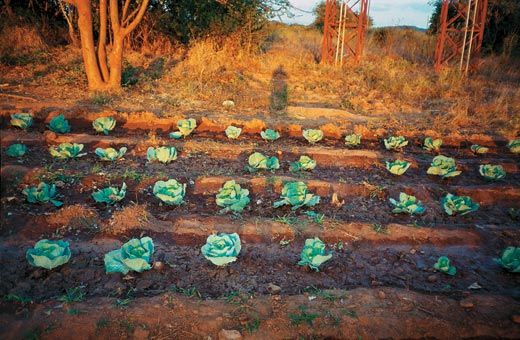

Klaus Schoenwiese traveled down the road eight miles north of Lusaka, Zambia, through soft hills, still lush from the rainy season, and fields of maize that were beginning to dry. Charcoal sellers whizzed by on bikes. His Land Cruiser turned at a sign marked CCHZ. Along this rutted, dirt road were a few small farmhouses, open fields of tomatoes and a fluttering flock of blue finches.

Another turn took him to the Chishawasha Children's House of Zambia, an orphanage and school. In a yard shaded by low trees, Schoenwiese barely had time to step outside of his SUV before he was bombarded with hugs. "Uncle Klaus!" the kids shouted.

Schoenwiese, a 43-year-old native of Germany who lives in New York City, is a photographer specializing in travel and portrait work. He went to Chishawasha this past May with the backing of the New York City-based Kids with Cameras, which sponsors photography workshops for disadvantaged children. The organization was made famous by the Oscar-winning documentary "Born into Brothels," about its work with the children of Calcutta prostitutes.

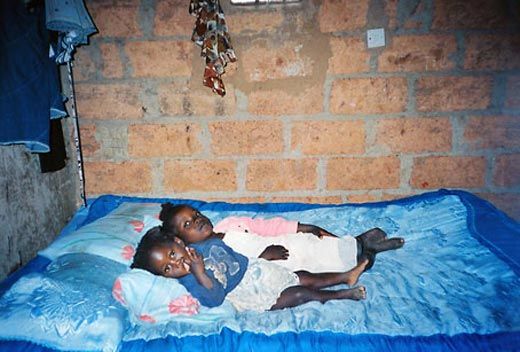

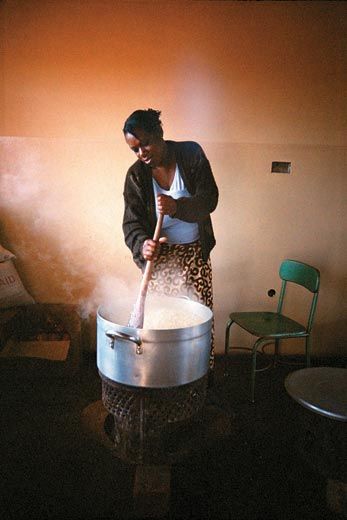

The Chishawasha facility and its sister non-profit organization, the Zambian Children's Fund, were founded in 1999 by Kathe Padilla of Tucson, Arizona, to serve children orphaned by AIDS. Chishawasha's three new concrete and mud-brick residences—the name Chishawasha means "that which lives on" in the local Bemba language—currently house 40 children, ages 3 to 19; another 50 children attend the school, which goes through the sixth grade. Zambia is one of the world's poorest nations, with about two-thirds of its population of 11 million subsisting on less than a dollar a day. One out of every six adults is HIV positive or has AIDS. More than 700,000 children have lost one or both parents to the disease.

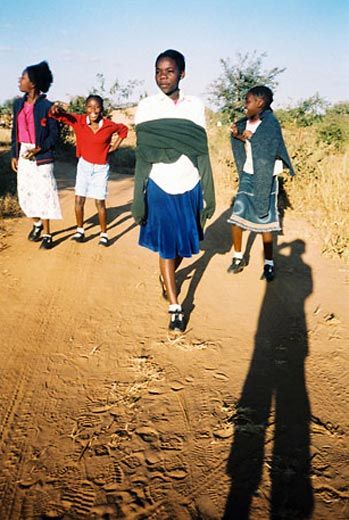

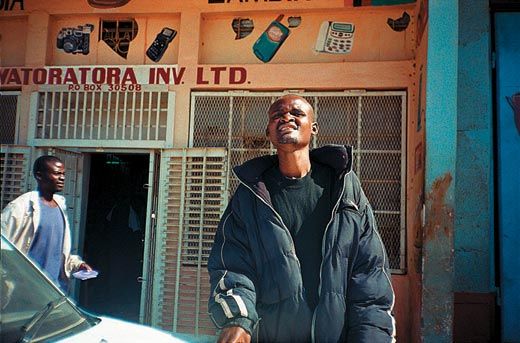

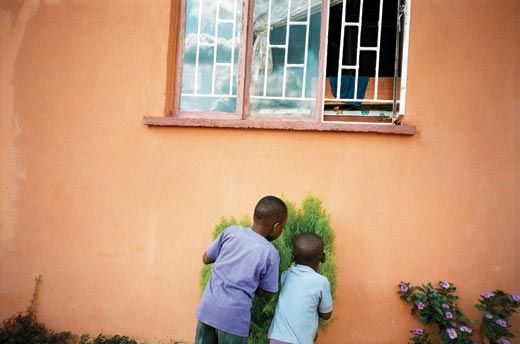

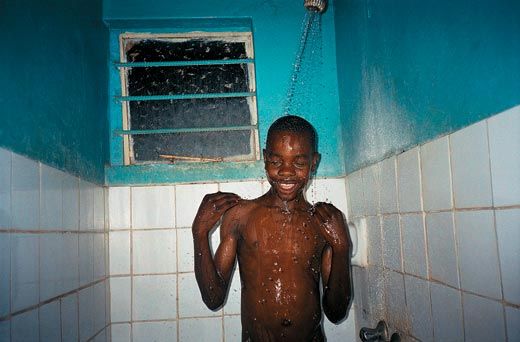

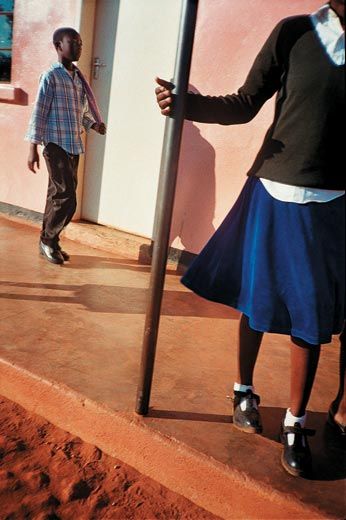

At Chishawasha, Schoenwiese gave the entire orphanage an introductory lesson in photography, but mainly he worked with a dozen students, ages 11 to 18. He said he chose the most introverted children, to "get them out of their shell." He provided them with 35-millimeter point-and-shoot cameras he bought on eBay, and developed and printed the film at a photo lab in Lusaka. Many of the kids had never used a camera, so there was some initial confusion about which side of the viewfinder to look through, and it was a while, he says, before most of the kids were able to "envision" a picture before creating it. Over three weeks, Schoenwiese gave the kids several assignments, asking them to document their surroundings and to take pictures of friends and family members. They also went on a mini safari at a resort hotel's game preserve, snapping away at elephants and zebras and then lingering by the hotel pool and laughing as they daintily pretended to drink tea out of china cups the waiters hadn't yet cleared away.

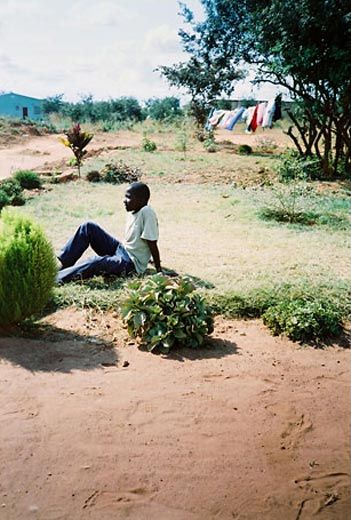

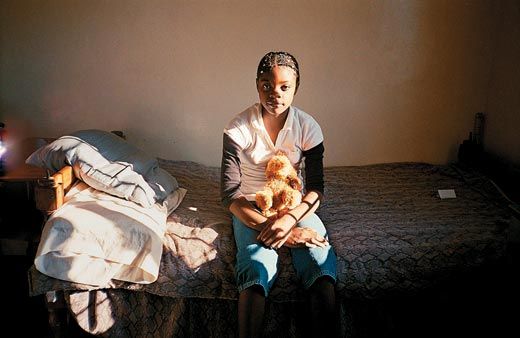

The idea of the photography workshop, in part, was to help the kids look at their world afresh. Peter, 11, who shepherds goats and likes to build toy cars out of wire, said he loved learning something completely different. Mary, 15, now thinks she wants to be a journalist. "I like the way they inform the world on what is happening in other countries," she said. "And I also hear that journalists speak proper English." Charles, 18, who has a knack for electronic gadgets—he'd rigged up a CD player in his room from discarded old parts—said he would rather be behind the camera than in front of it. Annette, 14, said she hoped that her photographs might someday appear in a magazine (see p. 101). Schoenwiese remembers an intense aesthetic debate with Amos, 13, who really liked a certain photograph he'd taken of a goat. Schoenwiese tried to convince the boy that a different photograph he'd taken of the goat was technically superior—sharper, with better contrast and exposure. Amos was unmoved. "One forgets that in our hyper-visual world these ideas are very subjective," Schoenwiese says.

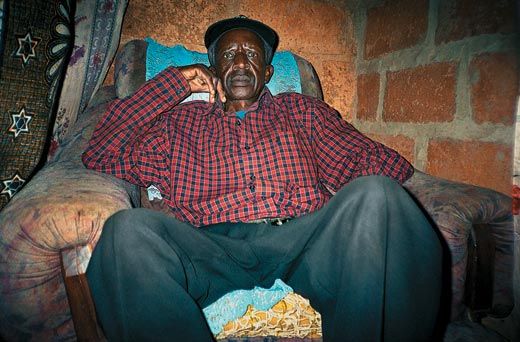

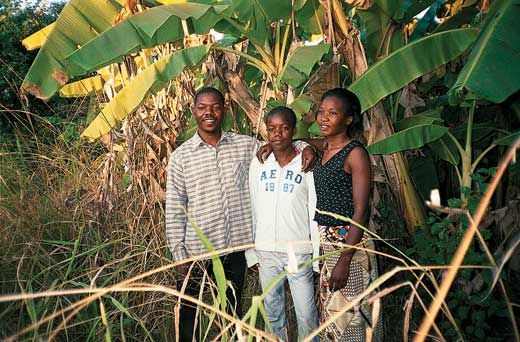

In another assignment, a Chishawasha student would go to a family member's home, and another student would photograph him with his relatives. Schoenwiese placed those pictures in albums for the kids to keep, part of an effort to add to their meager stock of mementos. "As orphans, many of the students have an incomplete knowledge of or are not quite in possession of their own personal history," Schoenwiese says. "They were especially eager to see their own presence and immediate relationships reflected in photographs." The kids went through the album pages in awe, recalls Mary Hotvedt, Chishawasha's development director. "With all the loss and prevalence of death in Zambia," she says, "these photos showed the kids that they really matter, that they really exist."

At the end of the workshop, the school exhibited 250 of the kids' pictures in a large classroom. More than 100 people showed up to gaze at the mounted 4-by-6-inch prints, many pinned from clotheslines. "The kids had a new way of seeing their families," Hotvedt says. "You could see how proud they were to say 'these are my people.'"

Schoenwiese features the students' work in an online gallery (tribeofman.com/zambia), and he's planning to sell prints of the students' work to support future photography workshops at Chishawasha. He's been a professional photographer for nearly two decades, but he says the youngsters—whose jubilant farewell party for him included dancing, singing, drumming and poetry—opened his eyes. "Despite their difficult past and their most certainly challenging future," he says, they "have an especially wonderful ability to live in the present. In that they have taught me plenty."

Jess Blumberg, a Smithsonian intern, is from Baltimore.