Photos Document the Last Remaining Old-Growth Pine Forests of the American South

In his forthcoming book, photographer Chuck Hemard delves deep into what remains of the longleaf pine forests of his youth

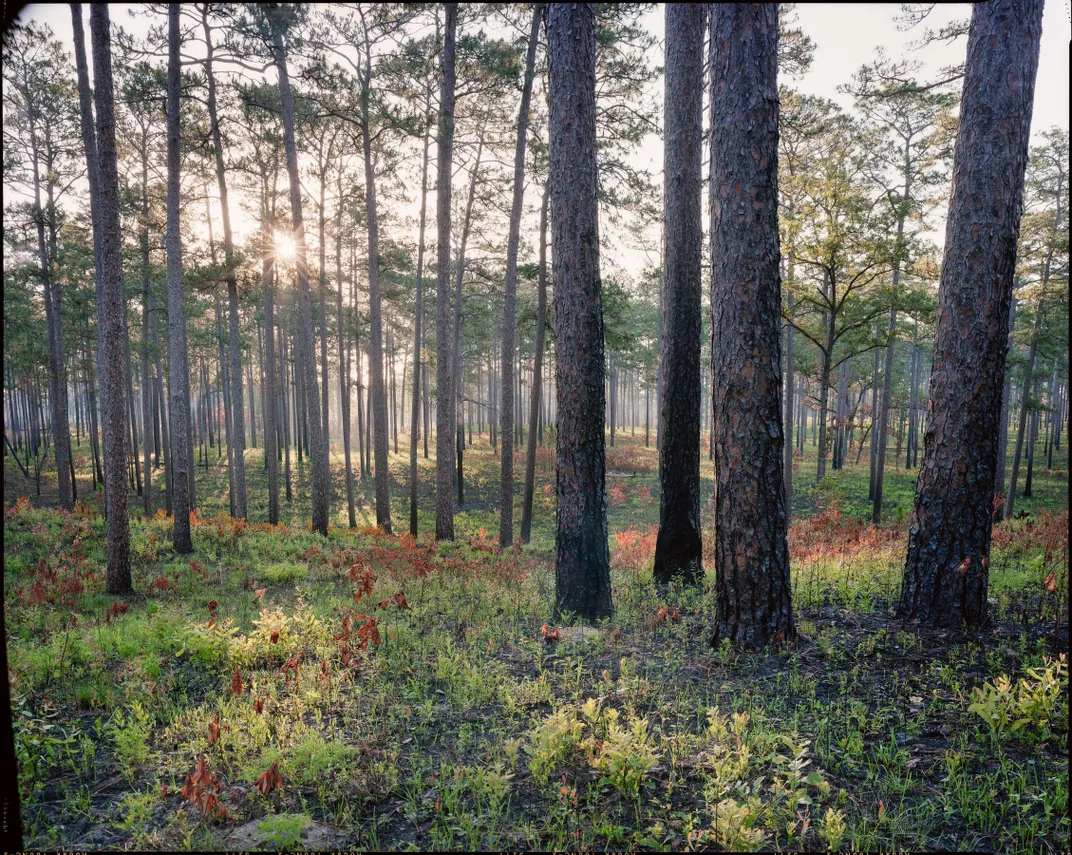

Before the early 20th century, longleaf pine forests were ubiquitous to the southern coastal plains, encompassing approximately 90 million acres of land. But years of deforestation by the logging and farming industries took its toll on the forested ecosystem, and today only 3 percent remains.

Growing up in the pine belt of southern Mississippi, Chuck Hemard would explore the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forest adjacent to his neighborhood, but it wouldn’t be until 2010 that the photographer would embark on a seven-year project capturing what still exists of the forests of his youth. Equipped with a 10-year survey documenting the locations of longleaf pine stands and multiple cameras, Hemard has created one of the most complete photographic compilations of this region.

“With pine trees still prominent across the region today, the significant change of the Deep South’s landscape is easily too subtle for most people to see,” Hemard says, “and thus is often overlooked even by residents of the region whose identity and sense of place is formed around a related but now different aesthetic of the countryside.”

Smithsonian.com talked to Hemard about his new book, “The Pines” (release date: February 13), mankind’s impact on southern forestry, and what can be done to preserve longleaf pine forests for future generations.

You grew up in the pine belt of southern Mississippi. How did the location inspire you to create a book about longleaf pines?

As a photographer, I’m always thinking about how a landscape can inform a sense of place, so I started considering my own personal history and its significance. I noticed that a lot of landscape photography in the United States is either about the American West or the romantic literature from the Northeast. The focus on the South is often about its cultural history, so it seemed interesting to me to do a book purely on a landscape that’s very regionally based. Growing up in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, there were longleaf pines everywhere, and as a kid it was my chore to rake up the pine needles in my yard. At the time I didn’t see them as special, but they became deeply seeded [in my memory]. I knew I wanted to photograph longleaf pines, but that’s kind of general and as an artist I wanted to set parameters for the project. I came across a survey of remnant, old-growth longleaf pine stands that still exist, so I thought it would be interesting to see what’s left of this original landscape.

Since 2010 you have been taking portraits of individual trees and calling them “Elder Portraits.” Can you explain the name behind the title?

Most of the pictures in the book I took using a large-format camera, which can be a slow working process because 8x10 film can be expensive, and I would often wait until the light was just right before taking a shot. To kill time, I would explore an area where potential pictures might be using a medium-format camera. I started taking photos of individual trees and saw them as portraits of old people. The gnarly branches and flattop crowns of these trees are similar to the wrinkles found on the faces of older people, suggesting the notion that age is a sign of wisdom.

What other characteristics make longleaf pine forests unique when compared to other forests in the country?

Longleaf pine forests are thought of as a keystone species of a larger ecosystem that has primarily adapted to fires, meaning frequent non-fatal fires like prescribed burns. If you look at maps that show where lightning strikes happen most frequently, the epicenter is in Florida and expands around the coastal plains from there. Fires would burn for hundreds of miles, and that was before the land was really developed. It’s not just the trees that have adapted to it at a young age, but the needles protect the terminal bud from fire. Even if the needles fall off during a fire, they’ll grow back. If you go [far enough] south in the coastal plains, you’ll find wiregrass, a specific clump grass that helps cure the fire. It doesn’t kill the fire, but rather gradually burns it off and then eventually resprouts. If this ecosystem is properly maintained with fire, it’s literally one of most biodiverse ecosystems there is.

At one time the longleaf pine forest was the most significant type of forest in the southern United States. Now only 3 percent of the original forests remains. What happened?

It’s mostly due to human intervention. Between the late 1800s to the mid 1900s, industrial-scale timber operations [increased in the area]. At first the harvesting of these trees was mainly confined to where there were streams and waterways to transport the logs to market. And then the railroad came along, so there was [suddenly] a way to get to untapped areas of this virgin longleaf forest and harvest the trees and bring them to market. Eventually, more and more saw mills were built in the area. It was originally this vast 90 million acres on the coastal plain that stretched from southern Virginia to east Texas. Only about 12,000 acres of old growth remain today. At one time this was one of America’s most significant landscapes.

Despite deforestation, many of the remaining longleaf pines you feature in your book have survived hundreds years. What do you think help accounted for their survival?

Because they’re literally remnants or leftovers, meaning at the time many of these logging sites had trees left on them that were either undesirable as merchantable timber, or located geographically on a spot that was hard to log.

I understand that you underwent training as a certified prescribed burn manager in the state of Alabama. What did you learn from this training?

I learned about weather conditions and how to predict the way a fire might behave. I think culturally, even here where it was common practice with development, it still freaks people out, especially seeing all the destruction in California with wildfires. But if people did more prescribed burning it helps reduce [how catastrophic a fire can be] because if you burn every few years there’s less [fuel on the forest floor] to burn as opposed to going 30 years between fires.

Currently longleaf pine forests are one of the most endangered forested ecosystems in the United States. What can be done to save them for future generations?

Slowing down the pace of progress and the short-sighted, often economically driven goals [of society]. When I say that these longleaf pine forests are biodiverse, there may be a species living there that we don’t even know about that could go extinct but may have had important things to teach us. There’s a quote in my book that says, “Even though humans can plant trees, we can’t re-create a forest.” Humans need to start looking at the bigger picture, stop acting like we’re in control, and be a little more humble.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/ac/54ac5bbe-6c9d-4f25-84a6-7f1e2a9af816/2_highlands_county_florida_2013.jpg)