A Photographic Tour of Abandoned Cold War Sites

In a new book, historian Robert Grenville explores the haunting beauty of nature reclaiming some of history’s most notorious sites

The Cold War, or the “war that wasn’t,” lasted from 1947 to 1991. The two main powers, the United States and the USSR, never actually attacked each other—instead, they flexed their muscles to intimidate one another, causing events like the arms race and the space race, and spurring proxy wars like the Vietnam War and the Korean War. Nevertheless, the two countries prepared themselves for an eventual battle, one that never happened.

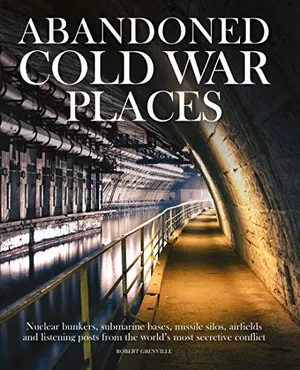

Historian and author Robert Grenville has immortalized some now-deserted sites of the conflict in his new book, Abandoned Cold War Places. In it, he compiles photographs of places built for or touched by the war, like an aircraft graveyard and decaying military housing.

“The book is a curated tour of the detritus left behind by both sides around the world during the Cold War—almost half of the twentieth century,” Grenville says. “The idea was to convey an impression of the scale of the confrontation and the legacy that endures to this day.”

Smithsonian magazine interviewed Grenville about the book, the most striking places and images, and the tendency for sites like these to become tourist attractions.

What was your motivation for creating this book?

I wanted to look at the physical legacy of the stand-off between these two power blocs. I grew up during the last few decades of the Cold War and that had a great impact on me. I remember seeing the pagodas in the misty distance at Orford Ness on England’s east coast and wondering what might be taking place inside.

What is it like to visit Cold War sites?

Cold War sites I’ve visited always have a certain atmosphere, a sense of the history that possesses even the most ordinary objects. With some of the less accessible sites, you get the strong sense that someone has just left the room to make coffee, and could at any moment walk back through the door. They are like time capsules. A good example is the image in the book showing a 1981 Russian newspaper pinned to a door, describing the events in the Soviet Congress that mentioned Mikhail Gorbachev. It is something to think about who might have pinned that up, and why. Where might they be now?

Abandoned Cold War Places: Nuclear Bunkers, Submarine Bases, Missile Silos, Airfields and Listening Posts from the World's Most Secretive Conflict

On the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, this fascinating visual history explores the relics abandoned when the Cold War ended.

In your opinion, what is the most interesting site in the book?

I find the bunker built for President Kennedy on Peanut Island in Florida to be fascinating. It was there for use if war was declared while he was at Palm Beach with his family. It’s believed that he never visited before his assassination, but the Presidential seal still sits on the floor ready for his arrival, even though the bunker is now decommissioned and declassified.

Could you share some of the compelling stories behind the sites?

I’ve always been fascinated by what happens to aircraft when they reach their end of life, and the U.S. Air Force has stored obsolete aircraft for years in perfect dry conditions in the Arizona desert that keeps the aircraft looking ready to fly. The fact that the U.S. recently rescued a former B-52 bomber from this scrapyard and brought it back into active service—after it had been flown originally for some 50 years—is incredible. In theory, some modern U.S. bomber pilots could be flying the same actual aircraft their grandfathers flew, albeit much updated.

Another favorite of mine is the bunker built at the Greenbrier Hotel in White Sulphur Springs for the House of Representatives. It stood ready for 30 years, for which the U.S. government paid the hotel a rent of $25,000 a year, until a Washington Post journalist stumbled upon its existence in 1992 and it had to be decommissioned.

Some of the sites featured are now not abandoned, but have been repurposed, such as the former base at RAF Upper Heyford in England used for shooting Hollywood films. Wonder Woman was filmed there, for example. Others will necessarily remain without human habitation for some time, like Pripyat, near Chernobyl, and the nuclear testing area in Kazakhstan that is especially haunting, where so many test devices were exploded over the years that the local population was badly affected by radiation poisoning.

Some of the sites—a former naval base on Russia's Pacific coast and a small Croatian island dotted with subarine pens and nuclear bunkers—have become tourist attractions. How do you feel about that?

If presented in the right way, I welcome it. It’s important for this part of our history not to be forgotten. A prime example is the various sites in Vietnam associated with the war there. The visitors they attract learn about the war from the Vietnamese perspective, and the sites’ accessibility encourages tourism to that part of the world.

Why is it important for people to know this history and see these photos?

It’s important to grasp the sheer scale of the Cold War and how far it reached around the globe. It certainly surprised me in working on this book. There’s a rusting tank on a beach in Yemen surrounded by goats, while in another section of the book, you see former U.S. radar buildings sinking into the Arctic ice in Greenland. But, for me, the images themselves have this special kind of beauty, seeing the decay that nature has wrought on these once-immaculate, sophisticated systems and installations.

What is the single biggest takeaway readers should get from the book?

Recent events have raised old, familiar tensions between the great world powers, even if those powers are no longer the same as they were 30 years ago. Most young people have not had to live in the shadow of an immediate threat of nuclear war, and the events of that era, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, serve as a warning to today’s leaders that a false step can quickly lead to potential catastrophe. I hope that readers might be inspired by the book to pursue their interest in the Cold War further—it is such a fascinating period of history that shaped much of our world today.

All images taken from the book Abandoned Cold War Places by Robert Grenville (ISBN 978-1-78274-917-2) published by Amber Books Ltd (www.amberbooks.co.uk) and available from bookshops and online booksellers (RRP $29.95).

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)