Inside Alabama’s Abandoned Buildings

As Birmingham flourishes again, an urban explorer documents what is left behind

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/dc/28dcb781-3855-4bfd-9115-268d2019cfcb/haley_herfurth_-_empire4.jpg)

The hotel sparkled then, its 19 stories leaning against a sky made gray and gritty by furnaces to the north and east. Birmingham, Alabama's Thomas Jefferson Hotel opened in 1929 with a week of parties, dinners and dances—and the stock market crash that happened just weeks after the opening had seemingly no effect on the luxury hotel. Prohibition was no deterrent, either; bellboys sold smuggled liquor from the local police station to hotel guests. Over the coming decades, the segregated Thomas Jefferson played host to thousands, welcoming politicians like Presidents Herbert Hoover and Calvin Coolidge and celebrities like Ray Charles and Jerry Lee Lewis.

It was a glorious time for Birmingham's local hotels, an era in which, as one journalist recalled, “a man could come into town with just a suitcase, put down a few dollars, and have a classy place to eat, get a haircut, hear some music, meet some people, and live.”

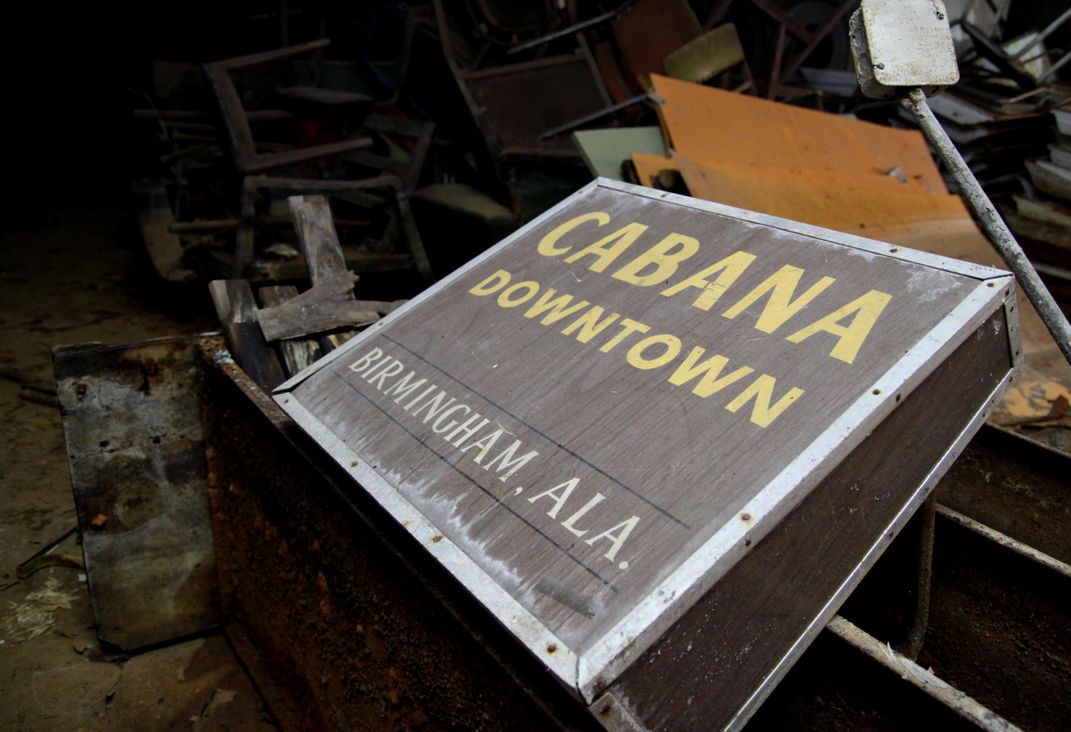

But those days didn’t last. The decades that followed broke the Thomas Jefferson. Renamed the Cabana Hotel in 1972, the oriental carpets were replaced with shag and the ceilings were dropped. By the 1980s, visitors could rent rooms for only $200 a month, and in 1983, the Cabana closed its doors.

One morning in 2009, before the sun rose, Alabama native Namaan Fletcher crawled through a small, broken window into the abandoned Thomas Jefferson, camera in hand. It was dark, and he was alone. “I was scared,” he tells Smithsonian.com, “but it was a rush.”

That first trip into the old hotel was part of the start of Fletcher’s urban exploration and photography hobby, which has since turned into his blog, What's Left of Birmingham and popular Instagram, @alabandoned. Since then, Fletcher has documented the decay of several of Birmingham’s oldest buildings, from downtown skyscrapers and banks to factories, schools, mausoleums and Masonic temples. Sometimes he gets permission for his visits; other times, he gets lucky, finding an open window or an unlocked door. “Trespass, sure,” he says. “But it’s a gentle trespass.”

The Thomas Jefferson is now known in Birmingham as the Leer Tower, a name given during the Leer Corporation’s failed $32-million redevelopment of the hotel into condominiums in the mid-2000s—though there are still rumors the project will resume in the coming months or years. Where there were once grand parties, Fletcher found only peeling walls and rotting mattresses.

Birmingham was once dubbed the Magic City due to its explosive growth as the South’s industrial center. The downtown area, once a mostly residential district with low-rise commercial buildings, grew upward in the early 1900s. High-rise buildings lined streets tangled with streetcar lines and the iron, steel and railroad industry supplied jobs for thousands.

World War II boosted the city’s economy even higher—from 1939 to 1941, Birmingham’s Tennessee Coal and Iron increased its workforce from 7,000 to 30,000. During this time, more than a quarter of the state’s rural black population moved out of state or into town in search of jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities as jobs formerly only available to white men opened up to people of color. African-Americans had achieved more equality during the war years; black veterans felt they had proved their patriotism. But much of Alabama’s white population resented the achievements and successes of African-Americans during the war. In many ways, World War II stimulated the Civil Rights Movement that was to follow.

As Birmingham became the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement, the city’s trajectory changed. In 1961, a mob of white men beat a group of Freedom Riders when their bus pulled into downtown. The following year, civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth secured a promise of desegregation of downtown water fountains and restrooms from Birmingham city officials, only for them to renege months later.

In April 1963, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference began its desegregation campaign, spurring sit-ins, marches and store boycotts. The campaign led to King’s arrest, and later that year, four young African-American girls were killed in the Ku Klux Klan’s bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Meanwhile, white residents fled Birmingham for outer suburbs like Hoover, Vestavia Hills and Trussville.

In 1966, the University of Alabama at Birmingham was founded on the Southside, sparking revitalization within city limits. But even as UAB grew to become a major medical and academic institution—UAB Hospital is Alabama’s major tertiary care center with nearly 1,000 beds and its university enrolls nearly 20,000 students from more than 100 countries—it wasn’t enough to stop the emigration of thousands of residents. Birmingham’s population was more than 340,000 in 1960. By 2010, that number had dropped to just over 212,000.

Now, there's another rebirth afoot in Birmingham. An influx of restaurant and bar openings and a revitalized music, arts and culture scene has brought substantial growth to the area, fueled by a tax credit and millions in investments. In the midst of the resurgence, Birmingham is achieving its new success within or alongside decaying remnants of its past. Many of the city’s older buildings are being converted or renovated into new spaces—old furniture buildings reimagined as high-end bars, civic buildings as residential lofts.

But many in Birmingham question whether the city’s growth is revitalization or white-driven gentrification. Citizens have complained that, while funds seem readily available to assist certain parts of Birmingham, traditionally black neighborhoods like Ensley, an east Birmingham suburb that was once a thriving industrial town, are left with roads full of potholes. And despite progress downtown, many old buildings, like the Thomas Jefferson, are promised new purpose with little follow-through. Other projects take years to complete after plans are announced. The photos produced from Fletcher’s visits to these places are some of his most popular.

One of the more well-known sites Fletcher has photographed is the American Life Building, a 1925 structure that has sat vacant since the 1980s. A 2004 plan to convert the building into condos failed, and a similar plan was announced in the late 2000s, only to stall out during the economic crisis. Through broken windows on its highest stories, iron furnaces are still visible in the distance.

A happier story, perhaps, is the Empire Building, a 16-story high-rise on Birmingham’s north side that was, until 1913, the tallest building in Alabama. By the time Fletcher explored the building in 2015, it sat in decay, the interior gray and mold-ridden. That same year, plans were announced to revamp the Empire into a luxury hotel.

Fletcher says he feels a kind of obligation to preserve these abandoned places on film, though he didn’t always see it that way. “I didn't start out to document for historical purposes,” he says. “It was purely selfish. I wanted to go to a place and take photos.” But over time, says Fletcher, he’s become what he calls a de facto historian. “People comment all the time on my blog with memories,” he tells Smithsonian.com. “These places meant so much to people and now they are just rotting. There are so many memories that float around in places. You can feel it.”

Now, Fletcher realizes the historical implications of his work. His photos of buildings slated for razing or restoration may be the last record of their place in Birmingham’s past. “The buildings I saw were molded, trashed, full of forgotten relics,” he says. “In a year or so, [some] will be pristine businesses and living spaces. I want to capture the images before they are lost.”

He recognizes, though, that many, if not all, of the downtown buildings he photographs share a one-sided history—and questions whether their future will look similar. “I’m sure [all of the locations I photographed] used to be segregated,” he says. “I wonder, to what extent they will be again once they’ve all been gutted and repackaged.”

In many ways, Fletcher’s work is a photographic narrative of Birmingham’s simultaneous growth and decline, a reminder that even as Birmingham grows, parts of the city’s past are being left behind. “Some people take offense to my work and its popularity,” Fletcher says. “They want everyone to know that my work is not representative of the city as a whole. ‘Birmingham is open for business!’ they say. I guess it is, but until you start selling these condos you are making, I'm not sold.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Haley-Herfurth.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Haley-Herfurth.JPG)