I saw her over the years standing on the corner, a beautiful old lady with secrets to tell. Although she had fallen on hard times, you could still see glimpses of her glory: her proud and striking face, her grand and imposing stature, the way she commanded attention from the street, like some last elegant remnant from days gone by.

Yes, she was a hotel, but I have always been in love with hotels—their history, their hospitality, their heart—and in the case of this hotel, the Lutetia, the horror. She was the only grand hotel on the Left Bank of Paris, a Cinderella overlooked and overshadowed by her fabulous stepsisters on the Right—the Ritz, the Crillon, the George V, the Plaza Athénée and the Bristol—which flaunted their dominance while the Lutetia remained mostly silent.

Owners came and went, and the darker parts of its history were recalled only in fading memories of people who didn’t seem eager to revisit the place. Because they were there when evil ruled the world, and the old hotel served first as a headquarters for hate and later as a haven for its victims.

Then, around 2014, events colluded to tell all.

First, there had been a best seller entitled Lutetia by the acclaimed Moroccan-French novelist Pierre Assouline. Next, an exhibition, illustrating the hotel’s painful past, and then a companion documentary, Remember Lutetia. Added into the mix was a buyer, an international real estate firm that purchased the Lutetia for nearly $190 million, determined to not only restore the old glory but to give the hotel a rebirth with a radical $230 million restoration unveiled last summer.

“Welcome to the Hotel Lutetia,” the front desk receptionist, a young man named Kalilou, who tells me he is from Mali, greets me when I check in for a four-day stay.

While awaiting my room, I settle into the library, a light-filled, high-lacquered salon filled with the latest picture books of the good life. I listen to the bleeding voice of Billie Holiday and recall something the actor Tom Hanks had written in his collection of short stories, Uncommon Type: “A good rule of thumb when traveling in Europe—stay in places with a Nazi past.” Within the hour, I am in love with the new Lutetia, its bright new light and whitewashed walls, its perfumed air, its glossy, burnished teak guest-room hallways, which resemble the passageways of a grand yacht, its bustling Bar Josephine, which overlooks the busy Boulevard Raspail, its cradling staff and superb cuisine.

I could have happily stayed forever.

But I wasn’t there on holiday.

I’d come to meet the ghosts.

* * *

“You think when you take the corridor, you are going to turn and see a phantom,” says general manager Jean-Luc Cousty, who has served the Lutetia in various positions on and off for 20 years. “Even if you don’t know the history of the hotel, when you enter the building something happens. It is very sensitive and emotional....When you are entering a house of ghosts, you can be afraid. But that was not the case at all. Because this is a building where there is humanity. Since the beginning, this hotel has been a reflection of what is happening in Paris and the world.”

Given a hard hat and a reflector vest a few months before the hotel’s reopening, I take a tour of the Lutetia. Gone are the dark guest rooms, replaced with sleek and modern quarters and Calacatta marble bathrooms, reduced in number from 233 to 184, the extra space given to 47 suites with grand views. Gone are ancient layers of age and seven layers of ceiling paint, beneath which work crews discovered lush 1910 frescoes by the artist Adrien Karbowsky, which took restorers 17,000 hours to bring back to life. Even the front stairs and extravagant exterior have been sandblasted to perfection.

Atop the new Lutetia, I look across a pretty little park, Square Boucicaut, to where it all began: the monolithic department store Le Bon Marché, started in the mid-19th century by a former traveling fabric salesman, Jacques-Aristide Boucicaut, and his wife, Marguerite, who turned their small sales operation into “the good market.” In his novel Au Bonheur des Dames, Émile Zola called a fictional emporium based on Le Bon Marché a “cathedral of commerce.” The store was such a success that, after the founders died, the Boucicaut heirs, along with investors, decided to build a hotel for the store’s suppliers and clients, especially families from across France who made regular pilgrimages to Paris to stock their homes.

They planned to call it “the Left Bank Grand Hotel,” and its aspirations rivaled those of the Right Bank of the Seine. Its rooms had cutting-edge amenities, including air conditioning, and the latest in furnishings—from Le Bon Marché, naturally—all behind a soaring marble-white facade with carved embellishments representing the harvest, hanging bunches of grapes and other fruit, as well as frolicking cherubs.

“The hotel was inaugurated 28 December 1910, the turning point between Art Nouveau and Art Deco,” says the Lutetia’s historian, Pascaline Balland. (She is also the grandniece of a prisoner of war, who never returned from Buchenwald to the Lutetia, where his family sought news of his fate.) The hotel was christened with the Roman name for Paris—Lutetia—and took as its emblem a storm-tossed ship above the traditional Parisian motto Fluctuat Nec Mergitur—beaten by the waves, but never sinks.

In 1912, twelve salons were built to host special events. Orchestras performed in the balconies above the ballroom, their railings decorated with wrought- iron depictions of trailing grape vines, “deemed to be longer lasting than anything in nature,” according to the designer. But the parties came to an abrupt halt two years later with the onset of World War I. Overnight, half the employees, including the general manager, were shipped off “to fight the Germans,” says Balland. “The main salon was given to the Red Cross and beds were taken from the rooms for the injured.”

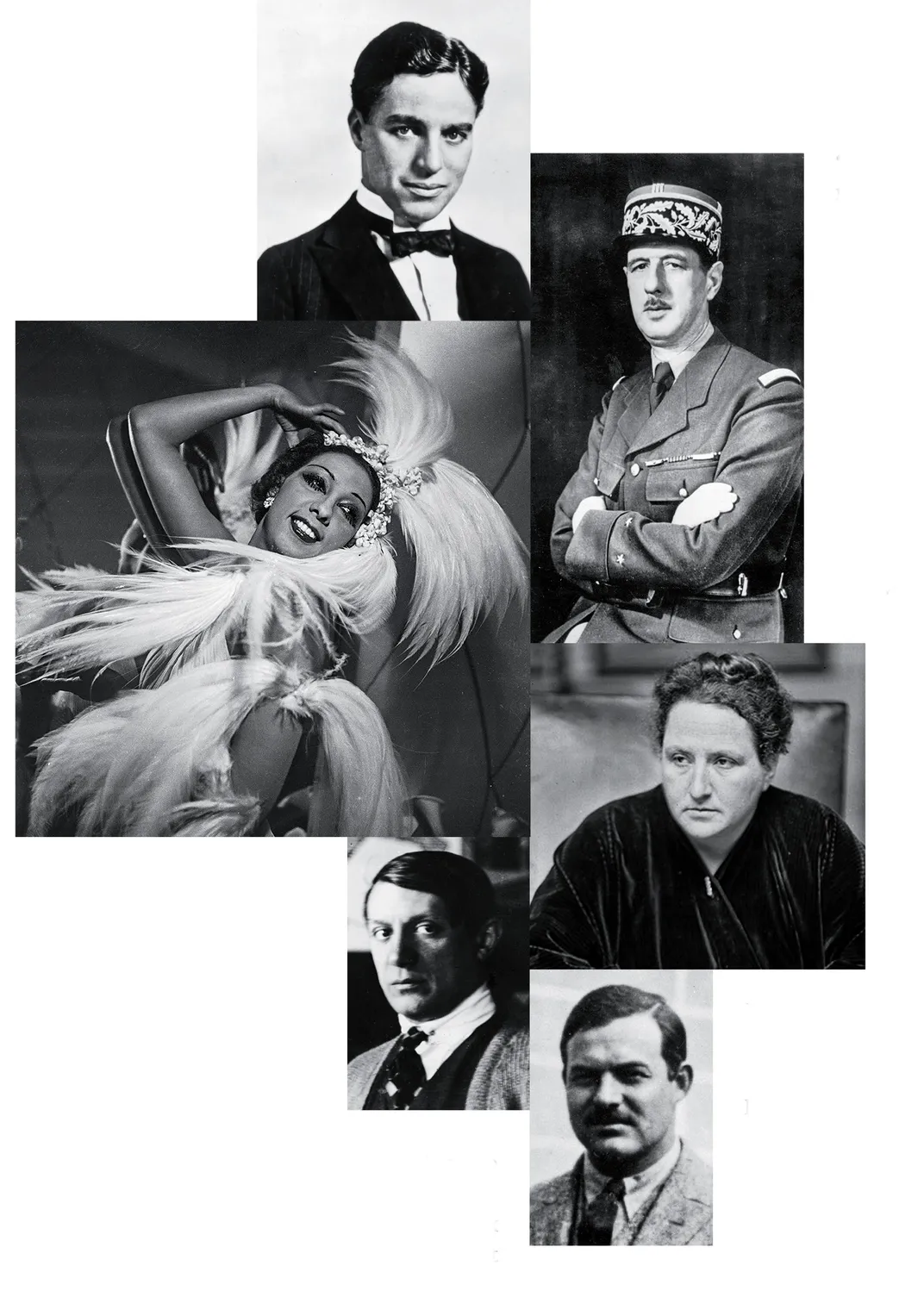

Emerging from the Great War, the Lutetia began to roar with the ’20s. Stars of the Lost Generation made the Lutetia their second home. The poet William Carlos Williams wrote about the hotel in his memoir. James Joyce fled his freezing Paris apartment for the hotel, where he played the lobby piano and wrote parts of Ulysses with the assistance of his private secretary, the future Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett. Hemingway drank in the American bar with Gertrude Stein. Other guests included Charlie Chaplin, Henri Matisse and Josephine Baker. François Truffaut, Isadora Duncan, Peggy Guggenheim, Picasso—all laid claim to the Lutetia at one time or another.

Among the distinguished visitors were two portents: Charles de Gaulle, a young officer and assistant professor of military history at the time, and the future president of the republic, who spent his wedding night at the Lutetia with his wife, Yvonne, April 7, 1921; and German novelist Thomas Mann and his brother Heinrich, who created the Committee Lutetia, meeting with other German émigrés in the hotel during the 1930s to plan a new government to take power after what they felt would be Adolf Hitler’s certain demise.

Instead, of course, Hitler conquered Europe and soon stormed Paris, where his armies took over the city’s best hotels. The Lutetia became headquarters of the counterintelligence unit, the Abwehr.

“I don’t know really how it happened,” says Cousty. “All the hotels of Paris were occupied. I don’t know why the Abwehr chose the Lutetia.”

* * *

When Pierre Assouline checked into the hotel during the early 2000s to research his novel, he learned things that shook him to his soul. “It was very emotional,” he says as we sit in a Paris café. He tells me of being caught up in the howling vortex of the hotel’s lore, the sleepless nights, the tears he shed onto his computer keyboard. While what he wrote was fiction, the novel was based on bloody facts.

Assouline’s protagonist is a detective named Édouard, who ends up investigating the hotel he thought he knew so well, having frequented its restaurant and bar for many years. “Before the war, the hotel was like a small town,” Assouline tells me. “You didn’t have to go out. They had a shop with all the newspapers from France and abroad, a hairdresser, groceries, restaurants, a patisserie, a swimming pool.”

The nightmare began in June 1940, when Hitler’s armies burst through the Maginot Line, a fortified wall military leaders foolishly believed could block the invading German Army. France surrendered, collapsed, fell, as Marshal Philippe Pétain advocated making terms with Hitler. On June 22, France signed an armistice agreement, relinquishing its rights to defend itself and promising to never take arms against its captors.

On June 15, 1940, the Nazis took over the Lutetia. Guests fled; most of the staff left in a panic. A swift-thinking sommelier secreted the hotel’s enormous collection of fine wine inside a freshly dug tunnel, whose entrance he hid behind a wall. (The Nazis would never discover the stash.)

When Abwehr Commander Oskar Reile, a thin colonel with closely cropped hair, entered the hotel, he was handed a glass of Champagne by a German officer who welcomed him. “The pastry shop and brasserie were closed,” Balland reports in her history, “the windows at street level blocked with a covering of pine branches attached to their frames, while wire fencing covered the facade and the main door.” The mailroom was turned into a dormitory. Each Abwehr officer was assigned to one of the hotel’s 233 guest rooms.

The Lutetia was now fully under the command of Berlin and the Abwehr’s admiral, Wilhelm Canaris, whose orders included interrogating suspected members of the Resistance network. (The Resistance was founded by de Gaulle, who had been so infuriated by Pétain’s cowardly truce with the Germans that he fled to Britain where he led a French government in exile.) The interrogation sessions were conducted in a room at the Lutetia with a view of the Cherche-Midi prison.

“The officers of the Abwehr were aristocrats, so they wanted everything to be up to their standards: silverware from Christofle, crystal from Baccarat, china from Haviland, and china from the Bon Marché,” wrote Assouline.

A maître d’ at the Lutetia named Marcel Weber seemed to be the only living survivor of the Nazi occupation to speak with director Hans-Rüdiger Minow, who filmed an interview in 1980, for his documentary Hotel Lutetia. “Before we even had time to realize they were there, the hotel had been requisitioned,” Weber says in the film. “We couldn’t believe it. I came up from the cellar to go to the street, then into the director’s office because they were all over the place.”

“We didn’t hear the sound of boots. It was more like a silent movie. It had happened. They were there. One of them immediately asked what there was to eat.”

Then the maître d’s memory seemed to shut down. “He was not so open to tell me the real truth about what happened,” Minow told me. The director believes that some hotel employees were turning a blind eye, and some collaborating with the Nazis. “Life could go on and it was possible to make money on the black market. I think a hotel like the Lutetia must have been involved in all of this.”

In the interview Weber spoke of Nazis gorging themselves in a mess hall set up in the former President’s Room; Nazis ordering wine and being told the cellar was dry, leaving the Germans only Champagne and beer; Nazis breaking from spying to go shopping, “returning with armfuls of boxes for their dear wives, shouting, ‘Ooh la la,’ shoes and a lot of other things at incredible prices....And they also appreciated French food, of course.” The staff, meanwhile, subsisted on cabbage soup.

Germany surrendered to the Allies in May 1945. Paris had been liberated on August 25, 1944. Four years after occupying the hotel, the Abwehr, still under the leadership of Oskar Reile, exited just as they had arrived, with Reile sharing Champagne with his men. “Then suddenly there was no one left,” said Weber.

The Nazis had deported 166,000 people from France to German concentration camps: their numbers included 76,000 Jews, among them 11,000 children, and many of the rest were members of the Resistance.

Only about 48,000 returned, and in France these displaced souls were given a name—the deportees. By a strange quirk of history, on their return from hell to humanity, many of them passed through the Lutetia.

* * *

Before the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the camps, in 2014, Catherine Breton, president of the Friends of the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation, was “looking for an idea of something to do,” she tells me. “At a time when France is welcoming so few refugees today, I wanted to talk about France’s hospitality in the aftermath of the war. I wanted to pay tribute.”

The group soon hit upon the idea of an exhibition about the Lutetia’s postwar role in receiving and processing concentration camp survivors. But the survivors, for their part, didn’t always want to remember, much less speak about that painful period. “These are forgotten stories,” she says. “The former deportees would tell me, ‘It’s not an interesting subject.’ They didn’t imagine that talking about Lutetia was a way to talk about everything: memory, people coming back, resistance, and to finally get the recognition of the status of these people for what they went through.”

The exhibit would be called “Lutetia, 1945: Le Retour des Déportés” (“The Return of the Deported”). Sponsored by the city hall of Paris and other organizations, it would honor the thousands of men, women and children who returned to the Lutetia for four tumultuous months between April and August 1945.

But when Breton and her associates began assembling the photographs, interviews, archives and memorabilia, they hit another wall: Most of the documentation was lost. So they unleashed the hounds of history: Researchers, many of them grandsons and granddaughters of the deportees, set out to uncover and document the survivors.

Alain Navarro, a journalist and author, began scouring the Agence France-Presse archives and discovered that a Resistance photo agency had been established to chronicle the liberation. “Someone went to the Lutetia in May 1945,” he says. “They shot maybe 20, 25 pictures. No indication of who were in the pictures. Jews. Slavs. Russians. People coming to the Lutetia. People inside the Lutetia. People waiting outside the Lutetia for the deportees.”

In one of those photographs, a dozen concentration camp survivors, many still in their tattered striped uniforms, sit in the hotel’s elegantly chandeliered reception room, tended to by smiling women, drinking from silver cups and eating crusts of bread, their haunted eyes peering out from emaciated faces. Another shows a young boy and his older traveling companion wearing concentration camp uniforms and sitting in a dark Lutetia guest room.

Who were these people and what were they doing in the luxury hotel? Navarro wondered.

That question caused a lost world to open, and the secrets of the old hotel to be told. Researcher and historian Marie-Josèphe Bonnet found much of the lost documentation, sifting through archives across France, unearthing long-forgotten ephemera from a time when war shortages of everything, including paper for newspapers, meant that much was never chronicled.

“Why did I work on the Lutetia? Because I am emotionally overwhelmed by this story,” says Bonnet. “Our family doctor was deported. When he came back from the camps, we could not recognize him—except through his voice.”

The floor of her small Paris apartment is covered with documents she unearthed. In a yellowed newspaper article she found a drawing of skeletal deportees in their striped uniforms: “The monthly report: 15 April 1945: To the free ones, men and women start to come back from the dead....You need only to go through the corridors of the Lutetia to see,” the story begins.

“I didn’t choose the subject; the subject chose me,” says filmmaker Guillaume Diamant-Berger, whom Catherine Breton enlisted to interview survivors for what would become the second stirring documentary on the hotel, Remember Lutetia. From the beginning, he was obsessed with learning what happened to his own family there. “My grandfather was always talking about the Lutetia. He went there for two months every day trying to find his family, the family that never came back. My grandfather had an antiques shop just behind the Lutetia. It was in his family for three generations. So it was inside my ear and my brain for many years. Catherine Breton had an idea for this exhibition on the Lutetia. And she wanted in the exhibition a video interview of survivors, which is how I got involved in the project.

“This story was like a gap or a hole inside the family,” he continues. “From the third interview, I realized I wanted to make a documentary about it.”

He filmed inside the ancient hotel before its years-long closure for renovation, its silent and gaping public rooms, its well-worn suites, where antiques buyers and souvenir seekers trudged, many buying the hotel’s remains—furnishings, art, dishes, everything down to the bedsheets. He enlisted actors to narrate the writings and recollections of those who passed through the Lutetia after the war. He interviewed the handful of survivors who had once arrived there with numbers on their forearms and their striped uniforms hanging off their bones. “This was really the first time they were telling their stories,” he says. “But they always speak about the camps, not what came after. Here, we ask about the part they hadn’t talked about: going back, to life.”

* * *

“No one had any idea of what state they would be in,” wrote Pascaline Balland, describing the deportees’ return to Paris in her history. The original plan was to process them at the cavernous public train station, the Gare d’Orsay. Then came “the return of the skeletons,” as Pierre Assouline called them, requiring special care that no public train station could provide.

“When we thought of Gare d’Orsay to welcome the deportees we could not imagine the survivors’ conditions,” Olga Wormser-Migot, an attaché assigned to France’s ministry of war prisoners, deportees and refugees, later wrote in her memoir. “We thought that once the reception formalities were completed, they could go home and resume a normal life right away. However, we should have known. We should have been aware of the rumors from the camp.”

Along with the deportees, Charles de Gaulle returned to Paris. Given a hero’s welcome, the former exile became the head of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. When the Gare d’Orsay proved unsuitable for the deportees, de Gaulle took one look at a photograph from Auschwitz and knew the perfect place to receive them: a hotel. Not the Crillon or the Ritz, with their over-the-top luxury and walls of gold, but a hotel that was close to his heart, “his hotel,” wrote Assouline, quoting de Gaulle, “Vast and comfortable. Luxury is not noisy but sober,” and then adding, “For them, the general wanted the best.”

De Gaulle appointed three heroic women to head the Lutetia operation: Denise Mantoux, a Resistance leader; Elizabeth Bidault, sister of the minister of foreign affairs; and the legendary Sabine Zlatin, who famously hid 44 Jewish children from the Nazis in the French village of Izieu. The women would work with the Red Cross, medical professionals and other staff to receive the deportees, a group of volunteers that soon swelled to 600.

Survivors streamed into Paris from everywhere, traveling by every means of transport—car, train, foot, thumb—headed to a place where they would receive food, shelter and 2,000 francs (about $300), and a Red Cross coupon for a new suit of clothing: the Lutetia. The first ones arrived on April 26, 1945.

They came from Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück. Some escaped their bondage on foot, if they still had muscle and vigor, over the scorched earth and into Paris, war-torn and just liberated, its Nazi signage still in the streets.

“I was 15,” Élie Buzyn, now 90, tells me, of when he began running toward the Lutetia. His parents and brother killed by the Nazis, he was designated one of the “Orphans of the Nation,” and given a special visa. But when he left Buchenwald, he was sent to 40 days of quarantine in Normandy, where he heard a name that sounded like paradise: “A lot of people were talking about Lutetia,” he says. “There were good rooms and good conditions for the people who were in the camps.”

He didn’t wait for permission to leave quarantine; he escaped. “We hitchhiked,” he says. “We had the address of Lutetia. They gave us rooms, food and clothing, and we were able to stay there for a few days. It was a transit place to sleep in a good bed for a few days.”

Even today, secure in his fine Paris home, he seems uneasy over revisiting those memories, those nightmares. At Normandy, he recalled, there were survivors with him who had asked after the fate of family members, when they learned that he had been at Buchenwald and Auschwitz. In some cases, Buzyn says, he knew how some of those prisoners had died. But he kept silent. “I didn’t want to tell them the story, because it’s too horrific,” said Buzyn.

And if he did speak? “People didn’t believe our story. So I decided not to talk, because if I told my story, I might have committed suicide.”

“I don’t want to go over my story. I don’t like it,” the deportee and celebrated artist Walter Spitzer, now 91, told me in his studio.

“For 60 years, I talked to nobody about my parents,” says Christiane Umido, left alone at 11 when her Resistance member parents were sent to the concentration camps—until she was reunited at the Lutetia with her father, who described a forced march out of a camp under Nazi guard in the last days of the war, “his feet bleeding from the ‘Walk of Death.’

“People didn’t want to listen to this,” she says. “I tried, even with close friends.”

Such was the sentiment of many other survivors—until they were invited to take part in the exhibition. Most had arrived in Paris in open-air wagons, rolling through the war-torn streets and finally reaching the snow-white facade with its hanging grapes, vines, fruit and frolicking angels, the name Lutetia blazing high above in swirling letters and shimmering lights. The Boulevard Raspail in front of the hotel was crowded with more desperate souls: families holding cards with the names of the loved ones they’d lost. Lists of known survivors had been broadcast over the radio, published in newspapers and posted around Paris. Hundreds of photographs of the missing, posted by friends and families, occupied an entire wall of the hotel.

“The first camp survivors alight on the platform, and there is deep silence,” recalled Resistance member deportee Yves Béon. “The civilians look at these poor creatures and start crying. Women fall to their knees, speechless. The deportees proceed somewhat shyly. They proceed toward a world they had forgotten and didn’t understand.... Men, women rush at them with pictures in their hands: Where are you coming from? Have you met my brother, my son, my husband? Look at this photo, that’s him.”

“It was crowded, swimming with people,” one deportee was quoted in Diamant-Berger’s documentary. “Our camp mates kept arriving from the railway stations. It would never stop. And everybody would ask, ‘Did you know Mr. So-and-So? And I would answer, ‘No, I didn’t.’ They would show you pictures and ask, ‘Were they in camp with you?’ Then, I answer, ‘There were 30,000 people in the camp!’”

“There was misery everywhere,” says Walter Spitzer, who escaped from Buchenwald in 1945. “Crowded. A lot of people were crying. There were photos, and people asking, ‘Did you meet this one somewhere in the camp?’ It was impossible. People were coming up and holding the photos.”

Once they waded through the crowd, the Lutetia opened its marble arms in welcome.

“I arrived in front of this big luxury hotel,” Maurice Cliny, who survived Auschwitz as a child, told Diamant-Berger in his documentary. He spread his hands wide to convey the impossible enormousness of the place. “I never walked into any place like that, only seen in a few books or movies, never for real. So I stepped into that, what do you call it? Revolving door. And turned with it, and as I walked inside the hall, I got this spray of white powder, almost in my face. It was DDT to treat lice, a common pesticide at the time. Now it has proved to be dangerous. But at the time they were trying to be nice.”

I’m swirling through the hotel’s revolving door now, having walked up the same short flight of stairs from the street that the 20,000 deportees strode, trying to conjure up those times, when the hallways weren’t white but brown, and filled not with the wafting scent of designer fragrance, emanating from almost every corner of the new Lutetia, but the stench of what singer and Lutetia regular Juliette Gréco called “that blood smell that soaked their striped clothes.”

The trucks and buses and people on foot kept coming, an endless caravan depositing deportees in front of the grand hotel: 800 arrived on April 29 and 30, 1945, followed by 300 per day in May, and 500 a day from the end of May until early June, until between 18,000 to 20,000 had passed through its revolving doors. “There were so many from the beginning,” Resistance member Sabine Zlatin wrote in her memoirs. “They had to be washed, shaved, deloused.... Everything had to be done for those found in such awful condition....They would spend three or four days at the Lutetia, or a week.”

“The repatriated will be undressed, put all their personal effects in a bag, which will be disinfected,” Assouline wrote in his novel. “He will keep his personal valuable objects in a waterproof envelope around the neck. Coming out of the dressing room they’ll walk into the shower room. And the nurse will ask if they need to be deloused....They will be measured, weighed, vaccinated, screened for infectious diseases, especially STD, and then checked for cases of TB or other respiratory problems. The estimated medium weight would be around 48 kilos (95 pounds).”

There were questions and processes to give them papers for their new lives. “Political deportees, no matter their physical condition, should be treated like ill persons,” read a directive from the French government.

“They had lost memory of dates, the names of the commandos, their torturers were called nicknames or mispronounced names,” wrote Olga Wormser-Migot. “We have to tell them they can help us find the others, find the mass graves along the exodus roads; and possibly identify their executioners.”

“And then Paris and the Hotel Lutetia,” wrote survivor Gisèle Guillemot, the words from her memoir read by an actress in Diamant-Berger’s documentary, recalling an “elegant woman who welcomed us with care, but wore gloves....The Hotel Lutetia had tons of DDT to fight lice, all over the hair, in the mouth, in the nose, in the eyes, in the ears. Enough! I’m choking!”

The doctor looked at her, “the repulsive little animal I had become,” Guillemot added, and then “questions, questions endlessly.”

Among them were children, “adults too soon.” One of them was quoted in the exhibition, “Bitter, suspicious of adults and full of hatred against the Germans...we had to learn how to become children again.” And hiding among them all were impostors: Nazi collaborators masquerading as deportees in hopes of escape.

They “could not get used to comfort, with hot and cold water,” Sabine Zlatin said in a 1988 radio interview. “Some would say, ‘Is this true? Am I alive? Is this a sheet? Is this a real bed?’ So we hired social workers to help cheer them up and to tell them it is all true. You are free. You are in a requisitioned hotel. And you will soon go back to a normal life.”

Many slept on the floor, and, failing that, walked the hallways.

“They are coming back from hell,” says Assouline. “Can you imagine?”

I tried to imagine. I stood in those same halls, now pristine and white and filled with gaiety, and struggled to envision when 20,000 souls passed through this strange membrane between two worlds. As Gisèle Guillemot wrote, “When we entered the Lutetia we were just numbers; when we left we had become citizens again.”

I tried to get the old hotel that’s new again to speak to me. All I had as a window into its past were the interviews I’d done, the documentaries I’d seen and the exhibition, comprising 50 boxes of placards, featuring the unearthed documents and photographs. The exhibit was inaugurated in Paris in 2015, when it went on display for 15 days before going on tour across France, garnering an estimated 20,000 visitors at 48 sites. But it was not shown inside the Lutetia. Because, once again, the old hotel was being reborn, and was closed for its 2010 to 2018 renovations.

A few years before the closing in 2010, it had seemed as if the hotel was trying to forget its past. A group of deportees had been meeting for dinner at the hotel on the last Thursday of each month since the mid-1960s. There were speakers and remembrances and a meal overseen by management at a two-thirds discount. The dinners began occurring less frequently. At this point, the Lutetia was a “property,” as hotels are called today, no longer even owned by Parisians, but by an American hospitality conglomerate, Starwood Capital.

* * *

The Lutetia was officially closed as a repatriation center on September 1, 1945. In 1955, Pierre Taittinger, the 68-year-old founder of the Champagne Taittinger house and a Bon Marché board member, purchased the Lutetia from the Boucicaut family.

Champagne, jazz and good times returned along with the Champagne magnate. “The hotel was once again a place to be seen,” wrote Balland. “French President François Mitterrand held summits at the hotel and addressed the nation from its ballroom.”

The fashion designer Sonia Rykiel redecorated the hotel, beginning in 1979 and into the early 1980s, replacing everything dark and foreboding with the avant-garde. And for a time, Americans and other affluent guests did gravitate there. Actors and entertainers, including the French icons Gérard Depardieu, Catherine Deneuve, French singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg and Isabella Rossellini, made the Lutetia their second home. Pierre Bergé, co-founder of Yves Saint Laurent, checked in for an extended stay.

By 2005, when Starwood acquired the Lutetia, the investment firm planned to transform it into a reimagined Element by Westin hotel. “The first of a new brand,” recalled general manager Cousty. Shortly after, a group called the French Friends of the Lutetia was formed, made up of powerful Parisians and Lutetia guests from abroad. “They were able to list the building [for architectural preservation],” says Cousty.

In August 2010, a new buyer for the Lutetia was announced: the Alrov company. Alfred Akirov and his son Georgy—the firm’s holdings include the Set Hotels—had plans for a transformative restoration. The hotel that once housed Nazis was now in the hands of Jewish owners from Tel Aviv.

The Akirovs fell in love with “the Lutetia’s unique location, history and powerful position in the imagination of all Parisians,” says Georgy Akirov. They jumped at the opportunity to return the Lutetia “to its rightful position as the ‘living room of Paris’ in St. Germain,” he says.

And, says Cousty, “The association of deportees has been in contact to relaunch their monthly dinners at the Brasserie Lutetia.”

For the hotel’s new owners, Pierre Assouline has his own advice on Lutetia’s enduring legacy. “Never forget you bought a part of the history of Paris,” he says. “Part of this history is brilliant, pleasant, glamorous, the Lutetia of the beginning. But there is the Lutetia of the war and the Lutetia of the liberation. Never forget it.

“I would be very glad if in the main corridor, there is a vitrine,” he adds, referring to the display cases that line the lobbies of Paris’ palace hotels, filled with brightly illuminated goods from luxury retailers and jewelers. “And it would not be a place for handbags or jewelry, but for the history with the pictures.”

I looked for such an exhibition in the dozen vitrines in the new Lutetia’s lobby, but found them filled with only the typical luxury wares. So I searched for commemoration elsewhere: swimming in the white marble pool, soaking in the solid white marble bathtub, sitting in the spa’s white marble steam room. Finding nothing of the past there, I joined the present in the Bar Josephine, packed on this Saturday night with a line at the door, a band belting jazz and an army of hip bartenders dispensing artisan cocktails with names like Tokyo Blues and Le Rive Gauche.

“This is the hot spot in Par-ee, baby!” I overhead an American telling his wife.

I fled the bar for the boulevard, exiting through the revolving doors, which a producer had told Assouline could be a central character if a movie were ever made of his novel: each spin of the door revealing another epoch of the Lutetia. But tonight the door only delivered me to the street. I stared up at the hotel’s undulating facade. I could make out a faded white stone plaque, with a bouquet of dead flowers hanging from a ring beneath it:

“From April to August 1945, this hotel, which had become a reception center, received the greater part of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps, glad to have regained their liberty and their loved ones from whom they had been snatched. Their joy cannot erase the anguish and pain of the families of the thousands who disappeared who waited here in vain for their own in this place.”

Finally, it hit me. I hadn’t seen a ghost, but I had stayed in one: defiant, resilient and, true to the slogan that was bestowed at its birth, unsinkable.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/e7/d5e71d0f-99b7-4398-8111-09d3fc64968f/_opener_original.jpg)