On the Trail of Harriet Tubman

Maryland’s Eastern Shore is home to many historical sites and parks devoted to the heroine of the Underground Railroad

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Harriet-Tubman-underground-railroad-631.jpg)

The flat terrain and calm waters of Maryland’s Eastern Shore belie the dangers of the journeys escaping slaves made to reach freedom in the North. Burs from the forests’ sweet gum trees pierced the runaways’ feet; open water terrified those who had to cross it. As they crept over, around or through marshes and creeks and woodlands and fields, the fugitives relied on the help of Eastern Shore native Harriet Tubman and other conductors of the Underground Railroad resistance network.

On previous trips to the Eastern Shore, I had biked sparsely traveled roads past farmland or sped by car to the resort beaches of the Atlantic. After reading James McBride’s novel Song Yet Sung, whose protagonist, Liz Spocott, is loosely based on Tubman, I returned for a weekend with book-club friends to explore places associated with Tubman’s life and legacy.

Most likely a descendant of the Ashanti people of West Africa, Tubman was born into slavery in 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, about 65 miles southeast of Washington, D.C. After nearly 30 years as a slave, she won her freedom in 1849 by slipping over the Mason-Dixon line, the border between free and slave states. Yet she returned to the Eastern Shore approximately 13 times over the next ten years to help other slaves flee north. Because of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated the return of refugee slaves captured anywhere in the United States, Tubman brought escapees to Canada, becoming known as the “Moses of her people” during her lifetime.

Along with helping to free about 70 family members and acquaintances, Tubman toiled as an abolitionist; a Union Army spy, nurse and teacher during the Civil War; and later a suffragist, humanitarian and community activist before she died, at age 91, in 1913. Now, Tubman is more famous than at any time in the past. The state of Maryland is planning a park named for her, and the National Park Service may follow suit.

For today’s travelers, sites on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay associated with Tubman’s early life are conveniently organized along the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway. One of America’s Byways, as designated by the U.S. Transportation Department, it is a 125-mile self-guided tour dotted with stops that highlight not only Tubman’s life, but also the story of slavery and the slaves’ quest for freedom. Tourists can drive the entire route, taking up to three days—south to north, as fugitives moved guided by the North Star—or visit just a few sites.

On Saturday we took a walking tour of High Street, the brick-paved historic thoroughfare in the town of Cambridge, that culminated at the handsome Dorchester County Courthouse, built in 1853 (206 High Street; West End Citizens Association; 410-901-1000 or 800-522-8687). Tubman’s first rescue, in 1850, began at this site, at a courthouse that burned two years later. Tubman’s niece Kessiah was about to be sold at a slave auction on the courthouse steps when her husband, a free black man, managed to get her and their two children onto a boat to Baltimore, where Tubman met them and brought them to freedom.

We also stopped at the Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center (424 Race Street, Cambridge; 410-228-0401), an informative storefront operation where volunteer Royce Sampson showed us around. The museum has a large collection of photographs of Tubman, including a set of portraits donated by the National Park Service and a picture in which she is wearing a silk shawl given to her by Britain’s Queen Victoria.

At the Bucktown Village Store (4303 Bucktown Road, Cambridge; 410-901-9255), Tubman committed her first known act of public defiance, sometime between 1834 and 1836. When a slave overseer ordered her to help him tie up another slave who had gone to the store without permission, she refused—and when the slave took off, the overseer threw a two-pound iron weight at him and hit Tubman instead. Her subsequent symptoms and behavior—sleeping spells, seizures and vivid dreams and visions—strongly suggest she suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy, according to Kate Clifford Larson, author of Bound for the Promised Land.

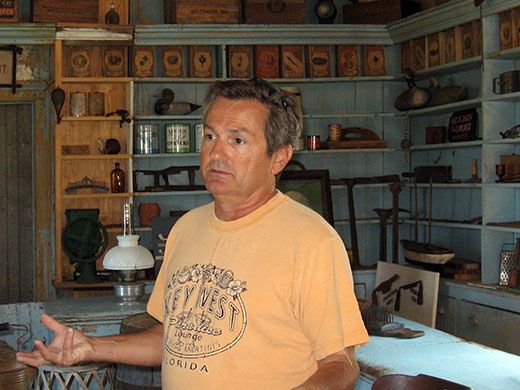

On Sunday Jay Meredith, the fourth-generation owner of the Bucktown Village Store, recounted this story in the restored building, where he and his wife, Susan, operate Blackwater Paddle & Pedal Adventures, which is certified by the park service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom to conduct bicycle and kayak trips. We rented kayaks for a jaunt on the languorous Transquaking River, which, though brief, made us appreciate how much Tubman had to know about her natural surroundings to make her way through a secret network of waterways, hiding places, trails and roads.

Ten miles southwest of Cambridge is the town of Church Creek, where Maryland is due to open a state park dedicated to Tubman in 2013, one hundred years after her death. The park’s 17 acres will be kept in their natural state so the landscape will appear much as it did when she traveled the area undetected.

On a grander scale, a bill was introduced in Congress Feb. 1 to create two parks to honor Tubman: the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, New York, where Tubman lived for more than 40 years, and the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park on the Eastern Shore. An additional goal of this bill is to encourage archaeological research to locate the cabin of Ben Ross, Tubman’s father, near Woolford, Maryland. The Maryland park would be on land within the 27,000-acre Blackwater Wildlife Refuge.

We arrived at Blackwater, famous for its nesting and migratory birds, early on Sunday morning (2145 Key Wallace Drive, Cambridge; 410-228-2677). With the help of a guide, we spotted bald eagles, kingfishers, great blue herons, cormorants, osprey, ducks and geese. Somehow it seemed fitting to see such a profusion of stunning birds, knowing that the refuge was only a stop for many—before they migrated to Canada.